mHealth self-care interventions: managing symptoms following breast cancer treatment

Introduction

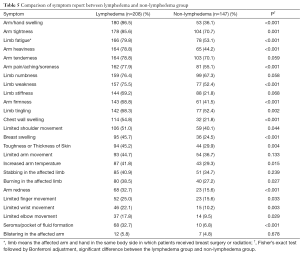

Breast cancer-related lymphedema (hereafter, lymphedema), an abnormal accumulation of lymph fluid in the ipsilateral body area or upper limb, remains an ongoing major health problem affecting more than 40% of 3.1 million breast cancer survivors in the United States (1-3). Lymphedema is a cardinal sign of an impaired lymphatic system (4-6). Impairment in lymphatic system leads to a chronic disease state with multiple associated symptoms that require ongoing symptom management (7-9). Similar to risk reduction and management of other chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes and prediabetes), proactive and preventive education on signs and symptoms of lymphedema and risk reduction activities is essential for early identification and treatment of lymphedema. Yet, this proactive approach to risk reduction is not a standard of care for those at risk for developing lymphedema associated with breast cancer treatment. Sadly, this leads to patients at risk for lymphedema self-diagnosing lymphedema and seeking professional help only after visible swelling is present. This reduces the opportunity for early identification and treatment which is associated with better patient outcomes. Recent research supports that more than 50% of breast cancer survivors without a diagnosis of lymphedema suffer at least one lymphedema associated symptom, pain (40%), tenderness (47.3%), aching (30%), or soreness (32.7%), tightness (34.7%), limited shoulder movement (28%), arm firmness (24%), arm swelling (17.3%), arm heaviness (14.4%) (4,7-9). This is not surprising, as even breast cancer survivors with lymphedema experience poorly managed symptoms such as pain (45.2%), tenderness (52.4%), aching (61.9%), soreness (31%), tightness (71.4%), limited shoulder movement (52.4%), arm firmness (69%), arm swelling (100%), arm heaviness (71.4%) in the ipsilateral upper limb or body (4,7-9). This profound disparity in the approach to risk reduction and symptom management in patients at risk for lymphedema has been further impeded by factors such as a lack of information about lymphedema symptoms, lack of guidance in how to assess lymphedema symptoms, and lack of standardized and effective interventions for managing lymphedema symptoms (10,11).

More importantly, the experience of lymphedema symptoms is a cardinal sign of an early stage of lymphedema in which changes cannot be detected by current objective measures of limb volume or lymph fluid level (4,7-9). Without timely assessment and intervention in this early disease stage, lymphedema can progress into a chronic condition that no surgical or medical interventions at present can cure (12). Notably, the experience of lymphedema symptoms is an ongoing main debilitating complication that elicits distress and impacts the breast cancer survivors’ quality of life (QOL) (13-15).The experience of lymphedema symptoms exerts tremendous limitations on breast cancer survivors’ daily living, making activities of daily living a source of intense frustration and unwelcome (13-15). With the increased rate and length of survival from breast cancer, more and more survivors are facing life-long risk of developing lymphedema, thus, managing lymphedema symptoms is essentially needed for breast cancer survivors at risk for lymphedema.

Patient-centered care is an ultimate aim of the healthcare system, and is fundamental to healthcare quality and equity (16). In spite of the growing body of evidence linking the experience of lymphedema symptoms to the higher risk of lymphedema, more distress and poor QOL (13-15), patient-centered care related to lymphedema symptom management is often inadequately addressed in clinical research and practice. The lack of patient-centered care for lymphedema symptoms has been evidenced by more than 40% of breast cancer survivors never receiving information about lymphedema (17,18). Critical to optimizing lymphedema symptom management, lymphedema symptoms should be regularly assessed not only by clinicians but also patients themselves.

mHealth can be broadly defined as the use of information and communication technology that is accessible to patients or healthcare professionals via mobile technology to support the delivery of patient or population care or to support patient self-management (19-21). mHealth plays a significant role in improving self-care, patient-clinician communication, and access to health information. A growing body of evidence has confirmed the positive impact of mHealth which supports patient-centered care (22-25). The-Optimal-Lymph-Flow health IT system (TOLF) is a patient-centered, web-and-mobile-based educational and behavioral mHealth interventions focusing on safe, innovative, pragmatic, electronic assessment and self-care strategies for lymphedema symptom management (26). The purpose of this paper is to describe the development and test of TOLF system to evaluate reliability, validity, and efficacy of mHealth assessment as well as usability, feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of mHealth self-care interventions for lymphedema symptoms among the end-user of breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Development and design of TOLF

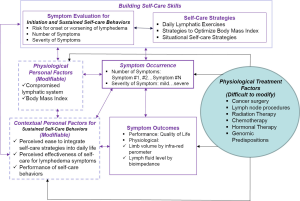

The development of TOLF was motivated by the request from breast cancer survivors in our prior research where nurse-patient-in-person delivery model was used (27) and guided by the Model of Self-Care for Lymphedema Symptom Management based on our prior research (28-31) (Figure 1). Symptoms are viewed as the indicators for abnormal changes in body functioning or side effects from cancer treatment as evidenced by research that lymphedema symptoms are significantly associated with lymphedema defined by >200 mL or 10% limb volume increase (4,7-9). Self-care for lymphedema symptoms refers to activities that individuals initiate and perform for themselves, without professionally administered treatments (e.g., by lymphedema therapists or nurses) (28-31). TOLF focuses on building self-care skills based on research-based, innovative, safe, feasible and easily-integrated-into-daily-routine self-care strategies to lessen lymphedema symptom burden (26,27). Detailed information about self-care skills as well as rationales and self-care actions is described in our prior research (26,27) (Table 1). Briefly, self-care skills for lymphedema symptom management consist of symptom evaluation, daily lymphatic exercises, strategies for optimal body mass index (BMI), and situational self-care strategies. To ensure mHealth intervention fidelity and transparency, we used avatar simulation videos to demonstrate lymphatic system, daily lymphatic exercises and strategies for optimal BMI (Figure 2). TOLF was designed according to key principles (32-39) that foster accessibility, convenience, and efficiency of mHealth system to enhance training and motivating symptom assessment and self-care for lymphedema symptoms among breast cancer survivors. Table 2 presents key principles of designing effective mHealth system and the implementation of designing TOLF. The homepage of TOLF that provides the introduction of the system can be accessed via the hyperlink (http://optimallymph.org).

Full table

Preliminary heuristic evaluation of TOLF

We completed preliminary heuristic evaluation with a relatively small group of 15 experts, that is, patients who have been formally prepared in human-computer interaction (HCI) and experienced in the design of interfaces, to examine the extent to which a user interface meets Nielsen’s principles for usability of the initial prototype of TOLF (32,33). Focus of heuristic evaluation is on visibility of system status, the match between system and the real world, user control and freedom, recognition rather than recall, and flexibility and efficiency of use (32,33). Each expert completed a set of specified tasks designed to explicate system features and also freely explore the prototype. The experts then completed a heuristic evaluation checklist by rating the severity of heuristic violations (no usability problem, cosmetic problem, minor usability problem, major usability problem, usability catastrophe) and provide additional comments regarding the interface (34). The experts only identified minor cosmetic problems of the system, such as making the font bigger, spelling errors, and comments on repeated information. The system was iteratively refined based upon the feedback of heuristic evaluation.

Testing of TOLF

We designed our testing procedures of TOLF based on the guidelines that foster accessibility, convenience, and efficiency of mHealth system (35-39) to undergo evaluation with usability testing, psychometric research to evaluate the reliability, validity and efficiency of assessment instrument administered by TOLF and pilot feasibility testing of TOLF interventions. Testing reliability, validity, and efficiency of assessment instrument delivered by mHealth system is imperative as the changes of user environment using electronic device may lead to changes of validity and reliability even in the case of using already established validity and reliability in the paper-pencil format.

Institutional Review Board approvals for the usability testing (IRB #14-10208), psychometric evaluation (HS#10-0251) and pilot feasibility testing (s15-00221) were obtained from the institute of the researchers in the metropolitan area of New York. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in the usability and feasibility studies. For the psychometric evaluation study, the completion of the study served as the participants’ consent. We followed the guidelines to protect human subject set forth by the Institutional Review Board and successful recruitment procedures used in our prior studies (4,10,11,15,17,18,26,27,30).

Psychometric testing

TOLF hosts electronic version of major clinical and research assessment instruments, including demographic and clinical information, Breast Cancer and Lymphedema Symptom Experience Index (BCLE-SEI) as well as Self-Care Behavior Checklist for intervention. These instruments were tested to be reliable and valid in pencil-paper format and have been used in several research (4,10,11,13,15,17,18,26,27). We designed a web-based study with cross-sectional design to (I) evaluate the feasibility of collecting data using TOLF system; (II) test the reliability and validity of the electronic version of BCLE-SEI among the end-user of breast cancer survivors.

Instruments

Demographic and Clinical Information tool is a structured self-repot tool that collects demographic and medical information (4,10,11,13,15,17,18,26,27). The demographic and medical information includes age, education, weight, height, breast cancer diagnosis, surgeries, lymph nodes procedure, radiation, chemotherapy, time since surgery, lymphedema diagnosis/treatment, hormonal therapy, and medications.

BCLE-SEI (4,10,11,13,15,17,18,26,27): a 5-point Likert-type self-report instrument consisting of two parts evaluating the occurrence of and distress from lymphedema symptoms. Part I of the instrument assesses lymphedema symptoms, including impaired limb mobility in shoulder, arm, elbow, wrist, and fingers, arm swelling, breast swelling, chest wall swelling, heaviness, firmness, tightness, stiffness, numbness, tenderness, pain/aching/soreness, stiffness, redness, blistering, burning, stabbing, tingling (pain and needles), hotness, blistering, seroma, limb fatigue, and limb weakness. A total of 25 lymphedema symptoms are evaluated. Each symptom is rated on a Likert-type scale from 0 to 4: 0= no presence of a given symptom; 1= a little severe; 2= somewhat severe; 3= quite a bit, severe; 4= very severe. Each symptom can also be treated as categorical variable with “0” indicating the absence of a given symptom, and “1”to “4” indicating the presence of a given symptom. Part II of the instrument evaluates the symptom distress, that is, the negative impact and suffering evoked by an individual’s experience of lymphedema symptoms, including daily living, function, social impact, sleep disturbance, sexuality, emotional/psychological distress, and self-perception.

Study participants

Women were recruited if they were: (I) ≥21 years of age who had surgical treatment (lumpectomy or mastectomy, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) or axillary lymph node dissection ALND); (II) with or without been diagnosed or treated for lymphedema. Women who received no surgical treatment for breast cancer were excluded since breast surgery and lymph node procedures are main contributing factors for lymphedema (5-7).

Recruitment

An open invitation to participate in the study was sent to more than 600 patient-members of StepUp-SpeakOut.org, an online community of breast cancer survivors with lymphedema or at risk for lymphedema via an electronic newsletter and posted on the organization’s website. The mission of the organization is to help breast cancer survivors to reduce their risk of lymphedema and promote effective management of lymphedema. If a member was willing to participate in the study, she would access the study through the link in the newsletter or go to the website. The completion of the study served as the participant’s consent. The study was open from April 20, 2010 through August 27, 2010. Of the 417 who accessed the study, only 335 women provided complete study data. Participants were informed of voluntary and anonymous participation.

Data management

Raw data were downloaded using the Excel files. Data cleaning was conducted via the Human-in-the-loop (HITL) method of a two-step process which requires human intervention when dealing with electronic data (10,11,40,41). The first step requires determining the most constant items which reflect the real number of respondents [constant items are those questions for which it is correct to provide only a single answer (such as “Are you currently employed?”)]. The second step involves identifying the number of duplicated responses. Data found to be duplicated were not included in the analyses. Table 3 identifies the key items/study variables that were checked and included in this study.

Full table

Data analysis

Statistical tests were estimated at the 0.05 significance level (2-sided) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Characteristics of the participants were summarized using descriptive statistics [means, standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and frequency distributions and proportions for qualitative variables]. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared for patients with and without lymphedema using Chi-squared (χ2) tests for contingency tables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency reliability of the total scale and subscale of symptom occurrence and distress of BCLE-SEI. The discriminant validity of the scale was obtained by nonparametric tests between breast cancer survivors with and without lymphedema. Fisher’s exact test followed by Bonferroni adjustment was also performed.

Usability evaluation of TOLF intervention

We conducted usability testing of heuristic evaluation and end-user testing with breast cancer survivors on TOLF intervention (33-35). We recruited 30 English-speaking breast cancer survivors over 21 years of age who had the various experience of using internet to evaluate TOLF intervention from October to December 2014. Participants provided written informed consent.

Study procedure

Participants completed a short questionnaire regarding demographic information and computer experience and use. Participants were asked to think aloud while completing a set of specified tasks designed to explicate TOLF features and also to freely explore the system either using a laptop or any electronic devices that they preferred. We recorded screen shots and participants’ utterances using Morae software™ (Techsmith Corporation, Okemos, MI), which allowed to record and analyze the audio recording and screen shots that were captured during the evaluation. Following completion of the tasks, participants were asked to complete a heuristic evaluation checklist that included ratings of severity of heuristic violations (no usability problem, cosmetic problem, minor usability problem, major usability problem, and usability catastrophe) and provided additional comments regarding the interface. Participants were also asked to complete two brief end-user questionnaires regarding their perceptions of information and system quality, and their behavioral intention to use the system using The Perceived Ease of Use and Usefulness Questionnaire (42,43) and The Post Study System Usability Questionnaire (44). Finally, participants were asked to provide narrative responses to the open-ended questions, “what do you like about the system”, “what do you dislike about the system”, and “what can be improved?”

Data analysis

We verbatim transcribed and summarized thematically the audio recordings of the think-aloud protocols and qualitative data from heuristic evaluation and responses to the open-ended questions. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic and quantitative data. Items in the Post Study System Usability Questionnaire were eliminated from the analysis as all participants marked “N/A (not applicable)” rather than assigned a numeric rating since the system does not require such functions for end-users to use the system.

Pilot of testing of TOLF intervention

We conducted a pragmatic, one-group, 12-week pilot trial of 20 breast cancer survivors to evaluate feasibility and efficacy of mHealth interventions to enhance self-care for lymphedema symptom management. The rationale for the 12-week intervention is based on research evidence for health habit formation (45,46): (I) It takes an average of 66 days to form a health habit based on daily repetition; (II) it is helpful to tell patients to expect health habit formation based on daily repetition to take around 10 weeks; (III) working effort fully on a new health habit for 2–3 months is an attractive offer for patients, and may help patients in making the health habit part of their daily lives. Building self-care skills for managing lymphedema symptoms is a process of making a health habit in which breast cancer survivors initiate and perform activities to prevent, relieve or decrease lymphedema symptom occurrence (i.e., number and severity of symptoms) and symptom distress as well as improve QOL (26,27). The primary outcomes of the pilot study evaluated by BCLE-SEI were symptom of pain, soreness, aching, tenderness and numbers of lymphedema symptoms as well as secondary outcome of symptom distress/QOL related to pain and symptoms. The efficacy of building self-care skills to manage pain and lymphedema symptoms was evaluated by patients’ report of self-care behaviors using self-care behavior checklist hosted by TOLF. Self-care Behavior Checklist is a structured self-report checklist that quantitatively and qualitatively assess participants’ practice of self-care behaviors at the study endpoint of 12 weeks after intervention (18,26,27).

Recruitment and procedures

We recruited participants using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria for the psychometric testing. Participants were recruited face-to-face at point of care during clinical visits at a metropolitan cancer center. To prevent technical skill barriers to access TOLF, researchers helped participants who had any questions or needs to setup or navigate the system. Each participant was given a user manual of a list of tasks to navigate the system. Participants were required to find the information and videos listed in the user manual. Participants had ongoing access to the program during the 12-week study period to review the material as needed using their own computers or laptops or iPad or other electronic tablets or smartphones. Participants were encouraged to enhance their self-care skills by accessing TOLF and following the daily lymphatic exercises during the study period.

Data analysis

Frequency distributions and descriptive statistics were applied to the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample as well as quantitative data regarding intervention evaluation. McNemar’s Chi-square test was performed to determine the effect of the intervention on pain, soreness, tenderness, aching, and symptom distress/QOL at 12 weeks post intervention. Wilcoxon signed-rank test of non-parametric test was used to compare the medians of number of lymphedema symptoms between baseline prior to intervention and 12 weeks post intervention. Alpha level was set at 0.05 (P values <0.05) and 95% CI for all the statistical tests.

Results

Psychometric Testing

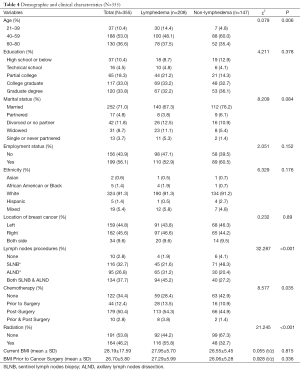

Of the 355 women who completed the study, 58.6% (n=208) of the participants reported having lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. Among the 208 women with lymphedema, 60.6% of them (n=126) had lymphedema more than 1 year and 36.1% (n=75) had lymphedema less than a year but more than 6 months, ranging from 6 months to 10 years of lymphedema history. Table 4 presents detailed information about the participants.

Full table

High internal consistency of the electronic version of BCLE-SEI was demonstrated with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.959 for the total scale, 0.919 for symptom occurrence, and 0.946 for symptom distress/QOL. Discriminant validity was supported by findings of a significant difference in symptom occurrence (z=–6.938, P<0.000) between breast cancer survivors with lymphedema (mean ± SD =27.22±14.43) and those without it (mean ± SD =17.31±15.51), a significant difference in symptom distress or impact on QOL (z=–5.894, P<0.000) between breast cancer survivors with lymphedema (mean ± SD =30.90±16.34) and those without lymphedema (mean ± SD =20.94±18.66), a significant difference in total scale of BCLE-SEI (z=–6.547, P<0.000) between breast cancer survivors with lymphedema (mean ± SD =58.12±28.22) and those without lymphedema (mean ± SD =38.25±31.75).

The mean number of symptoms experienced by the participants was 11.89 (SD =5.7) with a range of 0–25. By comparing the mean number between participants with and without lymphedema, symptom report was able to distinguish breast cancer survivors with and without lymphedema (t=5.379; P<0.001): Women with lymphedema reported significantly more symptoms (mean ± SD =13.12±4.87; median =14; ranging: 1–24) than those without lymphedema (mean ± SD =9.03±5.51; median =8; ranging: 0–23). Table 5 presents more detailed information regarding symptoms.

Full table

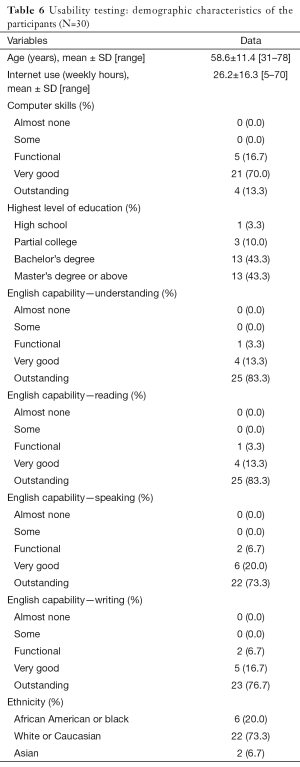

Usability evaluation of TOLF intervention

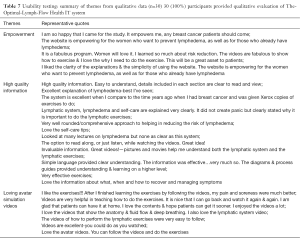

A total of 30 breast cancer survivors completed the usability study. Participants aged from 31 to 78 years, with mean age of 58.6 years and SD of 11.39. Table 6 provides more detailed information of the participants. The responses to Neilson’s heuristics (33) indicated no major usability problems or usability catastrophe with TOLF: 90% of participants (n=27) rated the system having no usability problems; 10% (n=3) noted minor cosmetic problems, such as spelling errors. We iteratively refined TOLF based on the feedback from the participants. Agreement for ease of use exceeded 93.3% (n=28) assessed by the Perceived Ease of Use and Usefulness Questionnaire. There was no disagreement reported for ease of use except one participant reported neutral. For the Post Study System Usability Questionnaire, average ratings on all the items ranged from 1.1 to 1.4 on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). Importantly, there were no neutral and disagreement scores (>3) on any item. Several themes emerged from the qualitative data analysis. These themes included empowerment, high quality information, loving avatar simulation videos, easy accessibility, user-friendly. Table 7 provides representative quotes for the identified themes.

Full table

Full table

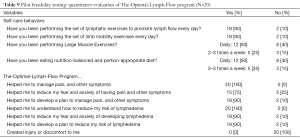

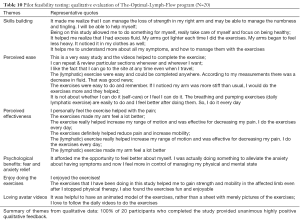

Pilot feasibility testing of TOLF intervention

Table 8 provides detailed information regarding participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics. At 12 weeks post intervention, participants reported less pain/tenderness/aching/soreness and lymphedema symptoms (χ2=6.40; 95% CI, 0.00–0.80; P=0.022) from baseline prior to intervention. Similarly, participants reported less pain at 12 weeks post intervention (χ2=6.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.85; P=0.031), less soreness (χ2=6.40; 95% CI, 0.00–0.80; P=0.021); less aching (χ2=6.40; 95% CI, 0.00–0.032; P=0.021), and less tenderness (χ2=5.44; 95% CI, 0.00–0.032; P=0.039). In addition, there was a significant decrease in the count of lymphedema symptoms from baseline prior to intervention (median =6; IQR, 2.25–9.50) to 12 weeks post intervention (median =1; IQR, 0.00–4.75) (P=0.003).

Full table

At 12-week post intervention, in terms of symptom distress/QOL, participants reported that pain had less interference with their enjoyment of life (χ2=7.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.69; P=0.015), less interference on normal work (χ2=7.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.69; P=0.016); less difficulty in completing simple task (χ2=7.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.69; P=0.015); less experiences of being fed up and frustrated by pain (χ2=9.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.51; P=0.004). In addition, pain had lower negative affect on cleaning house (χ2=6.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.85; P=0.031). Pain had less negative impact on emotion of frustration (χ2=6.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.85; P=0.031) and being angry (χ2=7.00; 95% CI, 0.00–0.69; P=0.016). There was a trend that participants experienced lower negative impact of pain on leisure activities (χ2=4.50; 95% CI, 0.00–1.10; P=0.07). Furthermore, the daily 5-min routine avatar simulation video of lymphatic exercises provided a unique way of helping breast cancer survivors to establish their own self-care routine by following the video. As our patients remarked, “the video helped to complete the exercises.” Table 9 and Table 10 present Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation of TOLF intervention.

Full table

Full table

Discussion

Distressed by lymphedema symptoms and worrying about developing lymphedema or progression to chronic and severe lymphedema has been a daily concern for breast cancer survivors (14,15). Findings of our psychometric testing demonstrate that TOLF system is able to collect data with high reliability and validity of the instrument to assess lymphedema symptoms and symptom distress/QOL in TOLF system. Our 355 participants representing 45 states in the United States demonstrates that it is feasible to collect demographic, health-related, lymphedema symptom data using a user-friendly mHealth system with high reliability and adequate discriminant validity. In the era of online technology, mHealth designed for patients’ self-assessment can empower patients to take control of their symptom management as well as risk and progression path of lymphedema. Our study also provides supporting evidences that multiple symptoms have strong associations with lymphedema status and the use of lymphedema symptom report is valid with its discriminatory ability to distinguish patients with and without lymphedema.

High quality information regarding effective self-care strategies for lymphedema symptom management is key for patient-centered care. Participants in our usability and feasibility studies rated the usability high in terms of quality of information. All the participants agreed that the information provided by TOLF regarding lymphedema symptom management is clear, easy to understand, high quality, and empowering. Easy access to high quality health information for lymphedema symptom management is essential for patient-centered care to achieve health equity. Participants loved the fact that patients can access TOLF at anytime and anywhere and learn about lymphedema, symptoms, and self-care strategies at their own pace. As our participants commented, “portable”, “patients can have this at their fingertips”, “self-paced; can repeat & review particular sections.”

TOLF was designed to enhance fidelity, transparency, and reproducibility of intervention delivery for lymphedema symptom management by providing a novel training system using avatar simulation videos to assist breast cancer survivors in building self-care skills based on the request from breast cancer survivors in our prior research that used face-to-face, nurse-delivery model of intervention for lymphedema symptom management (26). These videos provide visual demonstration of how lymph fluid drains in the lymphatic system when performing lymphatic exercises. Participants in our usability and feasibility studies loved avatar simulation videos that help them to understand lymphatic system and learn daily lymphatic exercises. As our participants remarked, “I love the videos that show the anatomy & fluid flow & deep breathing. I also love the lymphatic system video.” Avatar simulation videos hosted by TOLF was able to train our participants do the daily lymphatic exercises, as our participants remarked, “I like the (lymphatic) exercises!!! After I finished learning the exercises by following the videos, my pain and soreness were much better.” Findings of our usability and feasibility studies demonstrate that TOLF is able to enhance the patients’ self-care skill building given that patients can review the self-care strategies on their own schedule and pace virtually anytime and anywhere.

The ease of accessing and navigating TOLF is enormously important to enhance patients’ engagement in using the system. All our participants in the usability and feasibility rated the use of TOLF very easy. The use of user manual that lists the tasks to explore the system for technical skill training enhances the perceived ease for our participants to use the system.

Limitations

Our participants in this usability and feasibility studies represented general breast cancer survivor population in terms of age, education, and ethnicity in the study institute. Yet, our participants had relatively high education level and were familiar with internet use. Further testing of TOLF is needed for breast cancer survivors with less education level or limited experience of using internet. In addition, randomized clinical trial was not used for the feasibility testing. It is important to note that the percentage of 58.6% participants in the psychometric testing were diagnosed with lymphedema, this was higher than current literature of 20–40% (1,2). This sample characteristics reflect the findings of prior research on breast cancer survivors that patients with lymphedema were more eager and motivated to participate in research on lymphedema related issues (1,2,13-17).

Conclusions

Findings of psychometric testing on the ability of TOLF system to collect health, clinical, research data support the reliability and validity of electronic instruments administrated by TOLF system. Findings of testing on TOLF system have provided evidence for breast cancer survivor’s acceptance, usability and feasibility of TOLF system to enhance self-care strategies for lymphedema symptom management. TOLF provides a much-needed mHealth system for advancing the science of self-care for lymphedema symptom management and a foundation for transformation of healthcare from reactive and hospital-centered to preventive, proactive, evidence-based, patient-centered and focused on well-being rather than disease.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Institute of Health (NIMHD Project # P60 MD000538-03), Pfizer Independent Grants for Learning & Change (IGL&C) (grant #13371953), Judges and Lawyers Breast Cancer Alert (JALBCA), and New York University Research Challenge Fund (Grant # R4198) with Mei R. Fu as the principal investigator for all the grants. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health and other funders. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Institutional Review Board approvals for the usability testing (IRB #14-10208), psychometric evaluation (HS#10-0251) and pilot feasibility testing (s15-00221) were obtained from the institute of the researchers in the metropolitan area of New York. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in the usability and feasibility studies. For the psychometric evaluation study, the completion of the study served as the participants’ consent. We followed the guidelines to protect human subject set forth by the Institutional Review Board and successful recruitment procedures used in our prior studies.

References

- Paskett ED, Naughton MJ, McCoy TP, et al. The epidemiology of arm and hand swelling in premenopausal breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16:775-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armer JM, Stewart BR. Post-breast cancer lymphedema: incidence increases from 12 to 30 to 60 months. Lymphology 2010;43:118-27. [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society (ACS). Breast cancer facts & figures 2015-2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. 2015.

- Fu MR, Axelrod D, Cleland CM, et al. Symptom report in detecting breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2015;7:345-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Langer I, Guller U, Berclaz G, et al. Morbidity of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLN) alone versus SLN and completion axillary lymph node dissection after breast cancer surgery: a prospective Swiss multicenter study on 659 patients. Ann Surg 2007;245:452-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boneti C, Korourian S, Bland K, et al. Axillary reverse mapping: mapping and preserving arm lymphatics may be important in preventing lymphedema during sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:1038-42 discussion 1042-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stanton AW, Modi S, Mellor RH, et al. Recent advances in breast cancer-related lymphedema of the arm: lymphatic pump failure and predisposing factors. Lymphat Res Biol 2009;7:29-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armer JM, Radina ME, Porock D, et al. Predicting breast cancer-related lymphedema using self-reported symptoms. Nurs Res 2003;52:370-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Zaniletti I, et al. Minimal limb volume change has a significant impact on breast cancer survivors. Lymphology 2009;42:161-75. [PubMed]

- Ryan JC, Cleland CM, Fu MR. Predictors of practice patterns for lymphedema care among oncology advanced practice nurses. J Adv Pract Oncol 2012;3:307-18. [PubMed]

- Ryan JC, Cleland CM, Fu MR. Predictors of practice patterns for lymphedema care among oncology advanced practice nurses. J Adv Pract Oncol 2012;3:307-18. [PubMed]

- Fu MR, Deng J, Armer JM. Putting evidence into practice: cancer-related lymphedema. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014;18 Suppl:68-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi S, Lu Q, Fu MR, et al. Psychometric properties of the Breast Cancer and Lymphedema Symptom Experience Index: The Chinese version. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016;20:10-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu MR, Ridner SH, Hu SH, et al. Psychosocial impact of lymphedema: a systematic review of literature from 2004 to 2011. Psychooncology 2013;22:1466-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu MR, Rosedale M. Breast cancer survivors' experiences of lymphedema-related symptoms. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:849-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- IOM. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC.: Institute of Medicine, 2001.

- Fu MR, Chen CM, Haber J, et al. The effect of providing information about lymphedema on the cognitive and symptom outcomes of breast cancer survivors. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1847-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu MR, Axelrod D, Haber J. Breast-cancer-related lymphedema: information, symptoms, and risk-reduction behaviors. J Nurs Scholarsh 2008;40:341-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein J, Knight A, Marinopoulos S, et al. Enabling patient-centered care through health information technology. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2012.1-1531. [PubMed]

- Shortliffe EH, Sondik EJ. The public health informatics infrastructure: anticipating its role in cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:861-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Electronic Health Records (EHR) Incentive Programs. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html?redirect=/ehrincentiveprograms

- Hoffman AJ, Brintnall RA, Brown JK, et al. Virtual reality bringing a new reality to postthoracotomy lung cancer patients via a home-based exercise intervention targeting fatigue while undergoing adjuvant treatment. Cancer Nurs 2014;37:23-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, et al. The effectiveness of Web-based vs. non-Web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith L, Weinert C. Telecommunication support for rural women with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2000;26:645-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein J, O'Connor G, Friedmann RH. Development and implementation of the home asthma telemonitoring (HAT) system to facilitate asthma self-care. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001;84:810-4. [PubMed]

- Fu MR, Axelrod D, Guth A, et al. A web- and mobile-based intervention for women treated for breast cancer to manage chronic pain and symptoms related to lymphedema: randomized clinical trial rationale and protocol. JMIR Res Protoc 2016;5:e7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu MR, Axelrod D, Guth AA, et al. Proactive approach to lymphedema risk reduction: a prospective study. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3481-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ridner SH, Fu MR, Wanchai A, et al. Self-management of lymphedema: a systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2011. Nurs Res 2012;61:291-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu MR, LeMone P, McDaniel RW. An integrated approach to an analysis of symptom management in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:65-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu MR. Breast cancer survivors' intentions of managing lymphedema. Cancer Nurs 2005;28:446-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu MR. Cancer survivors' views of lymphoedema management. J Lymphoedema 2010;5:39-48. [PubMed]

- Kreuter MW, Farrell DW, Olevitch LR, et al. Tailoring health messages: customizing communication with computer technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawerence Eribaum Associates, Inc.; 2000.

- Nielsen J, Landauer TK. A mathematical model of the finding of usability problems. In: Ashlund S, Mullet K, Henderson A, et al. editors. Proceedings of the INTERACT'93 and CHI'93 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Apr 24-29; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 1993.

- Bright TJ, Bakken S, Johnson SB. Heuristic evaluation ofeNote: an electronic notes system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2006;2006:864.

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD. Design effects in the transition to web-based surveys. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:S90-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nusbaum NJ. The electronic medical record and Patient-centered care. Online J Public Health Inform 2011.3. [PubMed]

- Hayslett MM, Wildemuth BM. Pixels or pencils? The relative effectiveness of web based versus paper surveys. Library and Information Science Research 2004;26:73-93. [Crossref]

- Beling J, Libertini LS, Sun Z, et al. Predictors for electronic survey completion in healthcare research. Comput Inform Nurs 2011;29:297-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cotten SR, Gupta SS. Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1795-806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sollenberger RL. Human-in-the-Loop simulation evaluating the collocation of the user request evaluation tool, traffic management advisor, and controller-pilot data link communications: experiment I - tool combinations. Retrieved July 20, 2016. Available online: http://hf.tc.faa.gov/publications/2005-human-in-the-loop-simulation/full_text.pdf

- Zaidan OF, Callison-Burch C. Feasibility of human-in-the-loop minimum error rate training. In: Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics, 2009;52-61.

- Dillon TW, McDowell D, Salimian F, et al. Perceived ease of use and usefulness of bedside-computer systems. Comput Nurs 1998;16:151-6. [PubMed]

- Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 1989;13:319-40. [Crossref]

- Lewis JR. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 1995;7:57-78. [Crossref]

- Lally P, van Jaarsveld CH, Potts HW, et al. How are habits formed: modelling habit formation in the real world. Euro J Soc Psychol 2010;40:998-1009. [Crossref]

- Gardner B, Lally P, Wardle J. Making health habitual: the psychology of 'habit-formation' and general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:664-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Fu MR, Axelrod D, Guth AA, Rampertaap K, El-Shammaa N, Hiotis K, Scagliola J, Yu G, Wang Y. mHealth self-care interventions: managing symptoms following breast cancer treatment. mHealth 2016;2:28.