Extreme body messages: themes from Facebook posts in extreme fitness and nutrition online support groups

Introduction

The fitness industry has experienced rapid growth in the last two decades leading to the development of several short-term, extreme nutrition and fitness programs advertised to “jump-start” a healthy lifestyle (e.g., 21 Day Fix Extreme, Hammer & Chisel, Bikini Body Guide, 21-day Challenge). These programs are considered extreme in that calories are strictly limited and counting macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein, and fat) grams is required, often by weighing out or strictly portioning food. Additionally, the exercise programs are high impact and extremely regimented, with little or no “rest” days included in the plan. Many individuals engaged in these programs use social media as a way of sharing challenges, successes, and gleaning inspiration from peers. Among women, there is ample evidence suggesting that internet and social media use and exposure is linked with body dissatisfaction and eating disorder behaviors (1-3). Tiggemann and Slater (3) found that time spent on the internet was associated with women’s internalization of “thin ideals” and increased motivation to become thinner. Moreover, Mabe et al. (2) demonstrated that women who used Facebook more frequently showed higher rates of disordered eating behaviors and weight/shape concerns (2).

Social media outlets are often laden with comments stemming from the “fitspiration” movement. Fitspiration is a recent Internet trend designed to promote what is deemed a healthy lifestyle. This trend, while designed to inspire people to lead a healthier lifestyle, causes several concerns; first, the majority of images posted depict one specific body type, thin and muscular, that is unattainable for most women (4). Secondly, there is often promotion of extreme attitudes toward exercise (e.g., “Crawling is acceptable, puking is acceptable, tears are acceptable, pain is acceptable. Quitting is unacceptable”; “Cellulite is an invented disease”; “Don’t listen to your inner fatty; she misses bread.”) (5). Previous studies of fitspiration have demonstrated that exposure to it is linked with negative body image and mood (6), and that women who post fitspiration have higher drives for thinness and compulsive exercise (1). Other research exploring internet-based content has shown the negative impact of “thinspiration” or “pro-ana” (pro-anorexia) websites. Thinspiration content idealizes images of thin women, stigmatizes overweight women, and motivates viewers to lose weight, even in unhealthy ways (7). Bardone-Cone et al. evaluated the impact of exposure to pro-ana website using an experimental design (8). Undergraduate females were randomly assigned to view one of three different types of websites. Participants exposed to the pro-ana sites reported lower self-esteem and a higher desire to engage in disordered eating behaviors compared with other participants exposed to different types of content (8). Though some servers have blocked pro-ana and thinspiration content, it is still widely accessible, along with fitspiration messages, which are more pervasive (9).

What has become even more concerning is the amount of dangerous content similar to fitspiration and thinspiration being presented on different platforms, under the guise of promoting health and wellness. For instance, a content analysis of healthy living blogs demonstrated that the content contained a variety of information related to problematic eating and body image (10). The research examining the types of messages being endorsed by websites or programs demonstrating intent to promote a healthy lifestyle is limited, and primarily has focused on fitspiration sites. With the growth of the fitness instructor, there are several other potential avenues for receiving harmful eating, exercise, and body image information. Individuals may be unaware of the detrimental impact of this information if it is presented as part of a program that is advertised to promote a healthy lifestyle. To our knowledge, there has been no research examining social media content on Facebook as it pertains specifically to short term, extreme fitness programs. Given the rise in popularity of these programs, and evidence of the negative impacts of fitspiration and thinspiration content as seen in other online settings, it is important to understand what content exists on these platforms for extreme fitness and nutrition programs, especially as this content may be presented under the guise of promoting a healthy lifestyle.

Methods

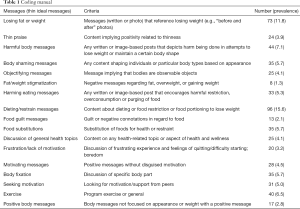

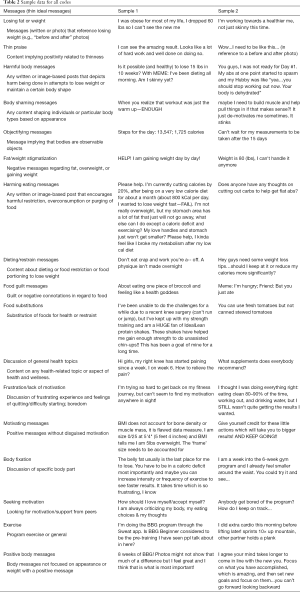

This study protocol was approved by the IRB at the researchers’ universities. The researchers developed a codebook based on research by Boepple and Thomson (2016 & 2014) relating to body image (9,10). The codes included losing fat/weight, thin praise, harmful body message, body shaming message, objectifying message, fat/weight stigmatization, harmful eating message, diet/restrain message, food guilt message, food substitution, frustration/lack of motivation, maintenance, motivating message, body fixation, seeking motivation, exercise program, and positive body message. Each code was defined to assist in proper coding. Table 1 provides a description of the inclusion criteria for each code.

Full table

The researchers selected all user data with discernable pieces of information pertaining to health, fitness, exercise, and nutrition over one month from public posts on two popular Facebook fitness groups. The groups were selected based on the large number of users (15,000 and 40,000, respectively). Additionally, these groups are free and open to the public to join. Finally, the fitness plans in both groups can be considered intense, with high impact exercises, and little or no rest or recovery. The diet plans in both groups can be considered extreme in that calories are strictly limited and counting macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein, and fat) grams is required. The function of the Facebook groups is to provide an online support group for members following the fitness programming and associated diet plan of each Facebook group.

User data included text (original user posts and comments), photos, emojis, and memes, which were compiled into Excel. Researchers individually coded the user data, and inter-rater reliability was computed using Cohen’s Kappa values and proportion of similarity between codes. Each post only received one code. An iterative process was used in which the researchers read and re-read the user data and assigned codes based on the manual provided in Table 1. A third party reviewed for similarity, which was initially 65%, with a Kappa value of 0.35. Researchers then individually re-coded the data and achieved a 74.6% agreement, with a Kappa value of 0.56 similarity. Any codes that the researchers had not agreed on were discussed via phone, until the researchers reached a consensus on each assigned code for all data, with a Kappa value of 0.92. After each unit of user data was assigned a code, the researchers calculated the total number of each code to determine the overall prevalence using Excel. See Table 1 for number of prevalence of each reported code.

Results

A total of 617 individual user data were extracted from the Facebook groups over the course of the selected month. 88.6% of the user data promoted harmful health and body messages. The most common codes were “diet/restraint messages” (15.6%), “losing fat/weight” (11.8%), and “harmful body messages” (7.1%). Many posts related to “losing/fat or weight” were those in which users shared personal experiences with weight loss:

“In April of this year I started my weight loss journey, I began just trying to go to the gym more and in general just make healthier food choices. I cut out pop for the most part. Started eating more green vegetables and eating more fruit. What I found to work for me so far is to stick to a 1,500 calorie diet (for the most part). I started to find exercises that I love like yoga and running. Well today I am super excited to say that I am…[at] my lowest weight in two years.”

Many of these posts were often accompanied by before and after photos (n=59; 80.8%).

Another common area related to “dieting/restraint messages”, which were characterized by individuals describing what foods they cut out of their diet (n=96; 15.6%) Participants wrote about various diet restrictions, such as:

“I try not to eat white flour, and I eat a lot of fruits and veggies, seafood and chicken. Red meat is almost gone from my menu plan. An occasional bowl of chili or hamburger. I do have a hang up about Tostitos and popcorn lately I am working on. My food weaknesses are French fries and ice cream almost never want to pass them up. I will pass on them when I know I have my limit of servings for carbs for the day.”

Participants also described ways they restrict their calories, for instance, intermittent fasting. One participant wrote, “I hit a plateau a while back, did this and it [intermittent fasting] snapped me right out of it.” Many posts involved the topic of meal prepping: “My biggest challenge was the meal prepping. It took me 2 hours to get everything prepped on the weekend BUT the POSITIVE is that I didn’t fall off the wagon.” Further, participants would describe moments of “success” and “control” with restriction: “We have an office tradition that I bake cakes for staff with birthdays. I am happy to report no [tasting] occurred in baking this chocolate peanut butter pile of temptation. I should get extra calorie burns for the amount of control displayed.” While not as common as dieting/restraint messages, user data also described food substitutions and food-guilt messages related to certain categories of food: “Had a stressing long 2 days. Had some wine and went cake tasting with a friend. I feel like a guilty child for those 2-day slip ups but back in the game today.”

The third most common category, “harmful body messages” promoted unhealthy and unsafe ways to attain certain body types (n=44; 7.1%). Many of these posts related to unhealthy calorie restriction, excessive exercise, and harmful exercise behaviors. One participant wrote:

“Do you feel like you’re doing everything right (eating pretty well, exercising) but you’re still not getting the results you want?? SO many people struggle with this—myself included! For years I thought to have the body I wanted (thin and muscular) the secret was exercising a ton and not eating very much.”

Another participant described feeling faint during exercise and guilt over stopping to rest:

“Yesterday I felt like I was going to pass out half way through my workout so I stopped and let my body rest. Later on, I went shopping and old thoughts began to creep in..you’re fat. Your sister is smaller than you. You aren’t beautiful. You need to be a 0/2 again. You need to lose weight.”

In response to a question about goals for the upcoming new year, one participant wrote: “To be healthy, happy and addicted to my workout.” Some posts also made reference to losing excessive weight in a short period of time, such as “Any one has luck losing 30–60 lbs in 2 months?” Finally, some of the user data coded as “harmful body messages” made reference to continuing exercise and dieting in times of illness. One participant wrote: “I just finished my antibiotics..I’ve had bronchitis and still feel a little low energy. Definitely better but not 100% should I get back to the gym or wait a few more days? I feel so guilty.” Another participant described being injured and feeling guilt about the interference with her workout routine: “I fell down the stairs in my back yard and hit hard on my back, so hard I couldn’t breathe, I have the heating pad on but this is going to screw up my workout.” These quotations illustrate some of the harmful health and body perceptions of participants.

Table 1 details the count and prevalence of each code. Table 2 provides sample data for each code.

Full table

Discussion

The data analyzed in this study represent overwhelmingly negative commentary relating to harmful health and body messages promoted by participants of extreme fitness and nutrition programs. These social media groups, though intended to be a sort of online support forum, actually provide an open space for body negativity and promotion of extreme behaviors for the sake of thinness. It is the extreme nature of the posts that worrisome. Several posts inquired about dieting while pregnant, exercising through pain, or exercising while ill. Other concerning posts were written by individuals who had “recovered” from an eating disorder or individuals with a genuine fear of weight gain. Even worse was the “support” in the form of further harmful advice from individuals who do not have the expertise to be doing so. Despite the wide variety of user data and codes used, four main findings emerged from the data: normalization of dysfunctional behavior, body part fixation, frustration and support, and body positivity.

Normalization of dysfunctional behaviors

The attitudes and behaviors described by the groups’ users help normalize destructive mentalities and behaviors, such as extreme dieting and calorie restriction, dieting while pregnant, exercising through pain, or exercising while ill. Many of these posts related to unhealthy calorie restriction, excessive exercise, and harmful exercise behaviors. User also sought praise for efforts to restrict and shared their “success” stories; for example, one user was seeking praise for the herculean effort to not eat a piece of cake. Though not suggested by a group user, a less destructive approach would be to occasionally enjoy cake instead of denying the treat. Common words describing the lack of control one felt over food included “failure” and “cheated”. Overall, the general message for individuals who join these groups is that weight loss and control, not health, is the goal at all costs. Often words like fitness and health were used synonymously with thinness, flat abdominals, and willpower, further normalizing these unhealthy processes.

Body part fixation

Another area commonly mentioned was the focus on a particular body part. Users posting before and after photos would focus on the torso and upper leg. Other users would post about wanting to lose fat in arms, belly, and legs. Some complained about how the fitness aspect of the program was adding bulk (muscle) to their legs, so much so that now their inner thighs touch eliminating the desired “thigh gap.” In both groups there was a strong emphasis on measurements of various body parts including waist, stomach, thighs, upper arms, wrists, and neck. Participants often discussed anxiety prior to taking these measurements at different checkpoints throughout the program, as their “success” hinged, not only on weight loss, but reduction in measurements.

Frustration and support

For some, these Facebook groups functioned as an online support group, which is one of the main purposes of the group. Whether it was someone frustrated with a lack of progress or moving into a more challenging level of the exercise program, users had an opportunity to air their concerns and typically receive a response of support from someone who had been at that point and made it past successfully through perseverance and committing to the program. Some of these messages were encouraging, promoting healthful ideas, practices, and norms, while others were promoting harmful behaviors. Many individuals would discuss their frustration with the inability to lose drastic amounts of weight in a short period of time and ask for suggestions for ways to speed up the process. These concerns were often met with suggestions to further restrict calories, use dangerous dieting strategies, such as intermittent fasting, or increase exercise amount and intensity.

Body positive

A bright spot in these Facebook groups were the few comments that were attempting to provide commonsense health information, coded as positive body messages and motivating message. These messages promoted a balanced lifestyle, happiness, and confidence. One even suggested to throw away the scale, pointing out that the number there does not define us. Other messages focused on “non-scale victories”, in which the users described the health benefits that they felt, such as increased energy. Some users discussed the importance of viewing developing healthy habits as an accomplishment itself, emphasizing healthy behaviors over physical appearance and changes. These messages, however, were limited and only accounted for 2.8% of the user data examined.

The findings show that a variety of messages were displayed in these fitness groups, much of which indicates problematic behaviors and perceptions related eating and exercise. This is concerning because fitness programs are often marketed to promote healthy lifestyles, however much of the content reflected by these users indicated unhealthy behavioral and attitudes. There has been a growing body of literature surrounding the impacts of “fitspiration” and “thinspiration” indicating the negative impact these movements have (1,6,7). The content presented on these fitness pages very much resembled fitspiration content (5). This is problematic for individuals who are motivated to lead healthier lifestyles and who turn to these programs and platforms for assistance with doing that; these individuals then are confronted with extreme, often unhealthy, views on eating and exercise, which can lead to maladaptive behaviors. Indeed, there is even evidence demonstrating that websites described as promoting healthy living contain some information promoting dysfunctional behavior (10). This trend is troubling as these messages may be reaching individuals outside the fitspiration movement and perpetuating dysfunctional behavior. Our study builds off of Boepple and Thomson (10), demonstrating these harmful messages are not siloed to the fitspiration, thinspiration, or pro-ana movements, but are prevalent in sectors of the health and fitness industry that are designed and advertised as promoting a healthy lifestyle. Implications from this study show that, while these fitness programs may not have the intention of promoting disordered eating, many of the participants describe concerning behaviors on public forums serving as support for those utilizing these programs. This is problematic as it could normalize disordered eating and exercise behaviors in a wide, international audience.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, this study was limited to two Facebook groups with publicly available user data. Data were also collected over the course of one month which limits the ability to understand the group users over an extended time period. However, there were an array of users in the groups that could be generally determined by the posts: brand new to the exercise/fitness program, started but stopped and were coming back, completed the program and were coming back after completing the first level of the program, and veterans of the program. User status was not analyzed because it was not always mentioned. Second, from this study, it cannot be determined whether individuals with disordered eating are more likely to join these programs, or if involvement in the programs leads to disordered eating. Future studies can expand upon this by evaluating disordered eating and exercise in participants of these programs to gain a more compressive understanding of the relationship between extreme fitness and nutrition program and these harmful behaviors.

The power of online social media platforms is definitive in these extreme fitness and nutrition Facebook groups. Women use these groups as a sounding board where they seek affirmation and feedback, while participating in programs that are said to value and promote health. As noted, the body negative and harmful posts add to the pervasive focus on physical appearance, objectification, and not overall health. It is possible that the messages seen in these groups are contributing to wide range of social media platforms that further disordered eating and exercise, eating disorders, and continue adding to a culture of women who value their physical appearance to the detriment of their health.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study protocol was approved by the IRB at the researchers’ universities.

References

- Holland G, Tiggemann M. “Strong beats skinny every time”: Disordered eating and compulsive exercise in women who post fitspiration on Instagram. Int J Eat Disord 2017;50:76-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mabe AG, Forney KJ, Keel PK. Do you “like” my photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. Int J Eat Disord 2014;47:516-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann M, Slater A. NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord 2013;46:630-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krane V. We Can Be Athletic and Feminine, But Do We Want To? Challenging Hegemonic Femininity in Women's Sport. Quest 2001;53:115-33. [Crossref]

- Boepple L, Ata RN, Rum R, et al. Strong is the new skinny: A content analysis of fitspiration websites. Body Image 2016;17:132-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M. “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women's body image. Body Image 2015;15:61-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borzekowski DL, Schenk S, Wilson JL, et al. e-Ana and e-Mia: A Content Analysis of Pro–Eating Disorder Web Sites. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1526-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bardone-Cone AM, Cass KM. What does viewing a pro-anorexia website do? an experimental examination of website exposure and moderating effects. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:537-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boepple L, Thompson JK. A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. Int J Eat Disord 2016;49:98-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boepple L, Thompson JK. A content analysis of healthy living blogs: Evidence of content thematically consistent with dysfunctional eating attitudes and behaviors. Int J Eat Disord 2014;47:362-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Blackstone SR, Herrmann LK. Extreme body messages: themes from Facebook posts in extreme fitness and nutrition online support groups. mHealth 2018;4:33.