Listening to the patients: using participatory design in the development of a cardiac telerehabilitation web portal

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of all deaths worldwide (1) and is often associated with low quality of life, memory loss, fatigue, depression, and anxiety (2,3). Cardiac rehabilitation is an effective approach for preventing secondary complications, but it remains a complex intervention that often requires patients to make both short- and long-term lifestyle changes (4). One solution for giving patients a better opportunity to adjust their behavior may be personalized rehabilitation programs that employ interactive telerehabilitation or eHealth web portals that can facilitate patient education. Patient education is a necessary step in helping cardiac patients understand and cope with their illness, treatment, and recommended lifestyle changes. Cardiac patient education provides patients with enhanced knowledge, facilitates behavioral change and can help them establish and maintain increased physical activity (1). In health care, the Internet and eHealth information portals are beginning to show potential as cost-effective methods that can improve both patients’ quality of life and serve as a useful tool for patient education (1,5). The use of digital technology overlaps with a paradigm shift in the clinician-patient relationship, where patients are now becoming more informed, involved, and active in managing their disease (6,7).

While many eHealth web portals have been developed, they have not been implemented as intended by developers (8,9). Several studies (5,7,10,11) indicate that in order for eHealth systems to be successfully implemented, the end-users’ needs and concerns must be taken into consideration. From our perspective, the chances of operational success become greater when employing a patient-centered participatory design (PD) process in the early design and development of the eHealth system (5,7,10,11). Our research project, ‘Future Patient-Telerehabilitation of Patients with Heart Failure’ (HF) (12), has used PD to develop an interactive portal for HF patients during their rehabilitation. The aim of this current study has been to evaluate the design and usability of a cardiac telerehabilitation web portal, called the ‘HeartPortal’, as used by patients with HF and healthcare professionals (HCP).

Context of the study

The overall aim of the Future Patient study is to develop an individualized telerehabilitation program for HF patients that can: (I) increase quality of life for HF patients; (II) teach HF patients to manage own disease with the help of new technologies; and (III) prevent or reduce the incidence of patients’ readmission to hospital.

The hypothesis in the study is that multimetric data (blood pressure, pulse, weight, steps, sleep, etc.) and issues related to the development of condition and the patient’s psychological well-being can help predict worsening of symptoms and the potential need to readmit the HF patients.

A core part of the Future Patient Telerehabilitation Program will be the online web portal, which we call the ‘HeartPortal’. The HeartPortal is a digital toolbox that allows HF patients and their relatives to manage their disease while also providing a communication platform connecting patients and HCP. Via the patient’s mobile devices, the HeartPortal collects data from the patient’s self-tracking devices (steps, pulse, respiration and sleep), CE-marked medical equipment (weight, blood pressure, and pulse), and questionnaires that measure the patient’s motivation, and potential degree of anxiety and/or depression. The next step in our study will be to test the Future Patient telerehabilitation program for HF patients who use the HeartPortal in a randomized controlled trial.

Methods

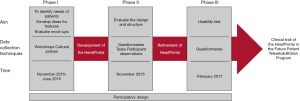

PD (5,13) has been used to design, develop, and perform usability test of the HeartPortal. The study was divided into three phases, as shown in Figure 1.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework is based on self-determination theory (SDT), and eHealth literacy (14-16). SDT conceptualizes motivation as based on the fulfillment of three essential psychological needs: (I) autonomy, which is a feeling that one’s behavior is in accordance with one’s internal values; (II) competence, a feeling of having the qualifications required to carry out a task; and (III) relatedness, which is defined as being understood and cared for by others. SDT theory is linked to types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic, corresponding to sustained internal desires versus short-term external pressures, both of which can affect behavior in different ways. When the three basic SDT needs are met simultaneously, it will lead to more intrinsic motivation, thus resulting in more persistent and more sustained, long-term lifestyle changing behavior, as motivation is no longer dependent on external factors (17). SDT is applied to stimulate the development of those features in the HeartPortal that elicit long-term motivation for a health-related behavioral change in HF patients. This is done by providing patients with opportunities to experience autonomy, such as making decision about their own rehabilitation program, and to increase patients’ experiences of relatedness in the healthcare settings; both factors are described as essential elements of SDT (18).

To achieve health-related behavioral change, it is also necessary for HF patients to have sufficient knowledge of what constitutes healthy behavior. As such, eHealth literacy skills are defined as the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise online health information from web portals, websites, and blogs (19-21). This particular skill is applied as a critical factor for designing components of the HeartPortal that can successfully target the individual patient’s needs and competencies, thus providing support for the second basic need of SDT-competency.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee (N-20160055), Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03388918). The study was reported to the Danish Data Protection Agency and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Phase I: development of ideas

Phase I had three overall aims:

- Identify and define the needs of HF patients and relatives in everyday life and their needs for effective collaboration with HCP;

- Develop ideas for specific features of the HeartPortal;

- Evaluate mock-ups of features for the HeartPortal.

Recruitment

In phase I, HF patients and HCP were recruited from the cardiology department at the hospitals in Viborg and Skive, and from the healthcare centers in Skive, Viborg, and Randers.

Participants in phase I of the study comprised the following groups:

- Patients diagnosed with HF NYHA class I–IV, above 18 years old;

- Patients’ relatives (spouse or near relatives);

- Nurses, doctors, nutritionists and physiotherapists working with rehabilitation of HF patients and representatives from the Danish Heart Association and a health technology company.

- An interdisciplinary research team within engineering, psychology and organizational sociology.

The phase I recruitment process ended up with a total of 59 participants: 21 HF patients, 13 relatives, 5 nurses at cardiology department/clinic, 4 nurses at healthcare centers, 5 physiotherapists, 2 cardiology doctors, 2 representatives from the Danish Heart Association, 2 company representatives and 5 researchers.

Data collection

A total of eight three-hour workshops were held at the healthcare centers in Randers (n=3), Skive (n=3), and Viborg (n=2). Cultural probes (22,23) were used to develop ideas about the challenges facing HF in everyday life (physical activity, diet, pain, sex life, etc.). Participants were encouraged to contribute ideas that could elicit intrinsic motivation for the patients so as to fulfill the psychological needs considered essential according to the SDT approach. The data presentation techniques used were brainstorming and posters that demonstrated the patient care process from (I) admission to discharge and (II) from discharge to home routines. Also used were theme cards for idea generation. Between the workshops, the data was documented and systematized, and mock-ups of potential HeartPortal features/menus were developed and evaluated by the participants in the workshops.

Phase II: evaluation of design and structure

The aim of phase II was to evaluate the design and structure of the HeartPortal.

Recruitment and baseline characteristics

Recruitment of HF patients in phase II took place from the cardiology department and the HF clinic at the Regional Hospital in Viborg headed by a project nurse. Ten new HF patients were selected according to the following criteria’s with the following characteristics;

- Patients diagnosed with HF NYHA class I–IV, above 18 years old;

- Current/recent signs or HF symptoms (>20% frequency);

- Living in Viborg, Skive or Randers Municipalities.

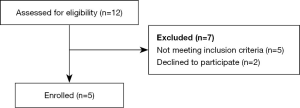

Figure 2 shows a flowchart of the recruitment process related to HF patients. Macefield (24) recommends that usability studies have 5–10 participants, which is why we have enrolled 10 participants in phases II and III.

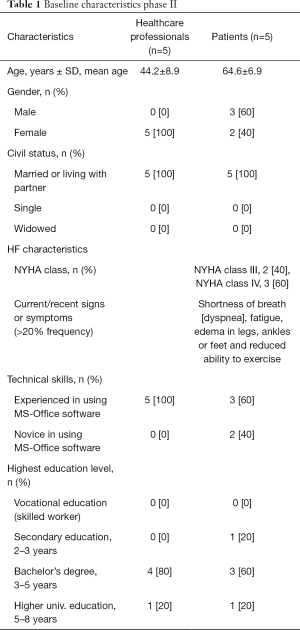

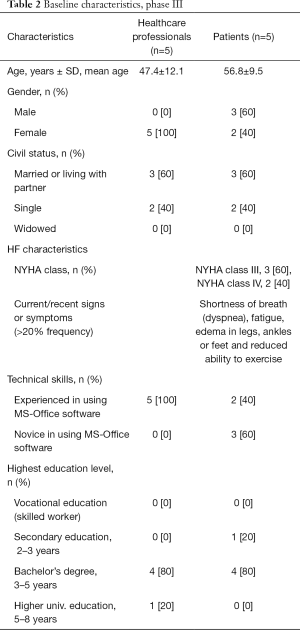

HCP were recruited by random selection among the HCP staff at the cardiology department and the HF clinic at the Regional Hospitals in Viborg and in Skive, with the assistance of by a project nurse. Table 1 shows the baseline data of the enrolled HF patients and HCP in phase II.

Full table

All 10 participants completed the questionnaires and participated in the tasks.

Data collection techniques

The structure and user-friendliness of the HeartPortal were evaluated using questionnaires and specific tasks. The questionnaires were developed and adjusted using techniques and experiences from validated questionnaires that had been used in a previous study (3), where a similar interactive web portal had been developed and tested (25). All questions were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale, and included three topics: (I) use of technology; (II) experience of user-friendliness; and (III) structure of the HeartPortal.

Phase III: testing usability

The aim of phase III was to test the usability of (I) the interactive information site and (II) the health monitoring and activity tracking module of the HeartPortal.

Recruitment and baseline characteristics

In phase III, how many HF patients were selected based on the following criteria (the recruitment criteria are exactly the same as in phase 1 and 2; so is this from the original group):

- Patients diagnosed with HF NYHA class I–IV, above 18 years old;

- Current/recent signs or HF symptoms (>20% frequency);

- Living in Viborg, Skive or Randers Municipalities.

The HF patients were recruited from the cardiology department and the HF clinic at the Regional Hospital in Viborg. The recruitment process was led by a project nurse.

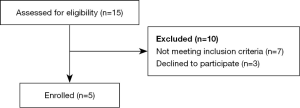

In Figure 3, there is a flowchart of the recruitment process related to HF patients in phase III.

A project nurse recruited the HCP by random selection among the HCP staff at the cardiology department and the HF clinic at the Regional Hospitals in Viborg and in Skive. Table 2 shows baseline characteristics of the participants enrolled in this phase. All participants completed the questionnaires (one participant did not answer two of the questions; these were classified as missing data using casewise deletion).

Full table

Usability testing

In order to test ease of usability, three tasks were developed so that participants could evaluate the logic and structure of the HeartPortal. The participants were given a tablet device with access to the HeartPortal and asked to carry out the following tasks: (I) find a video about living with HF; (II) find information about medicine; and (III) find the symptoms of HF. Each participant was asked to complete the tasks by navigating the HeartPortal menus while the researchers observed (26). A guide for observation was used, and the following themes were in focus: use of the tablet, non-verbal reactions, the participant’s need for assistance, questions asked by the participant, and time spent completing each task.

Data collection techniques

Data was collected using a questionnaire comparable to that used in phase II, with additional questions regarding data presentation and interpretation of graphical illustrations. All elements were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale, and the research group internally validated the additional questions. The questionnaire was divided into three subgroups: (I) use of technology; (II) experience of the content on the HeartPortal; and (III) presentation of data from different tracking devices.

Data analysis

During the phases in the PD process, data from cultural probes, ideas and notes on posters from the workshops and notes from researchers’ participant observations were systematized and condensed in NVivo 11.0, inspired by Brinkmann (27). The condensation of data was an iterative process among the researchers in order to ensure validation of data. Continuous data from questionnaires is presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical data are presented as frequencies with percentages.

Results

Phase I

In the workshops, participants expressed the view that they would like an interactive web portal with information on rehabilitation in text, audio, and video. They also stated that they wanted to be able to make their own notes, communicate with HCP and view data from their self-tracking devices in graphic form. Participants expressed the view that it was important that access to the portal be available for patients, their relatives, as well as HCP.

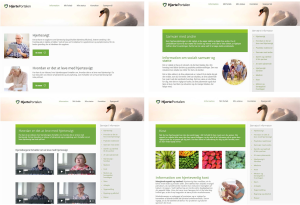

Based on the needs expressed in the workshops, the HeartPortal has been designed with four elements:

- An interactive information site that provides information on rehabilitation issues (smoking, physical and emotional status, diet, etc.) for HF patients in written texts and 1–2-minutes videos with patients and relatives who describe living with HF in their everyday lives;

- A health-monitoring and activity-tracking module receiving data from CE-marked medical and self-tracking devices that monitor blood pressure, pulse, steps, sleep, weight, respiration, and night pulse;

- Questionnaires on well-being. Every second week, the HF patients are asked to complete an online questionnaire on their sleep patterns, physical and psychological well-being via validated questionnaires [Spiegel Sleep Questionnaire (28) and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) (29)];

- A communication platform where patients, relatives, and HCP can communicate via a dialogue box and have access to the patient’s individual rehabilitation plan.

The HCP and HF patients can use the platform to set goals and write about activities in order to accomplish the goals. The HF patients also have the option of writing their own notes. Using the HeartPortal, patients, relatives, and HCP can access all data from the different elements.

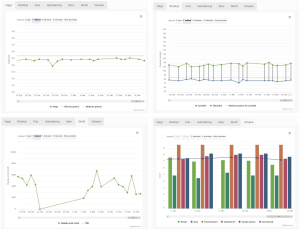

Figure 4 shows screen captures of various information pages from the HeartPortal, and Figure 5 shows examples of how data measurements (e.g., weight, blood pressure, steps, and wellbeing) are presented using a graph.

Phase II

The majority of the participants (HCP: 3/5 and patients: 4/5) who evaluated the HeartPortal have used a tablet several times a day. Overall, more than half of all participants ‘strongly agreed’ that the HeartPortal was easy to navigate, user-friendly, had a logical structure, and that they liked listening to other HF patients’ experiences on videos.

More specifically, 3/5 patients and 4/5 HCP reported that it was ‘very easy’ to navigate on the HeartPortal, 4/5 patients and 3/5 HCP ‘strongly agreed’ that the information was understandable, and 3/5 patients and 4/5 HCP ‘strongly agreed’ that the web portal had a logical structure.

Overall, most patients reported that the structure of the HeartPortal was ‘excellent’, which was not the case for the HCP. More precisely, 4/5 of the patients reported that the size and amount of text and size of videos were ‘excellent’, with 2/5 HCP reporting ‘good’. Furthermore, all patients (5/5) and 3/5 of the HCP reported that they found the structure of the web portal to be ‘excellent’.

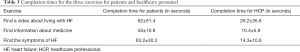

In all three exercises, the HCP used less time than did the patients (see Table 3), and the HCP appeared more relaxed when carrying out the tasks and did not request assistance. The reactions from some of the patients were bewilderment, lack of understanding of the tasks and hesitation before pressing a key. The patients also tended to read only the headings and not the accompanying text, which made the tasks more confusing. However, all patients eventually managed to solve the tasks within a reasonable period of time, and they all felt comfortable using the HeartPortal.

Full table

Phase III

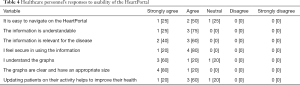

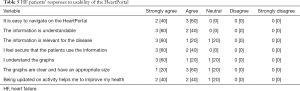

The participants who assessed the usability of the HeartPortal were all experienced users of tablet devices and smartphones. A general observation was that all participants felt comfortable using the HeartPortal, and they all agreed that the portal was easy to use, understandable, relevant to their disease and comprehensive. Furthermore, the majority of the participants felt that being informed about their activities through the tracking devices could help improve their health condition. The results from the usability test are shown in Table 4 for HCP and in Table 5 for HF patients.

Full table

Full table

The participants indicated that the graphs were slightly complicated to read. Finally, the HCP recommended that a function be added to the dialogue box by which all HCP could view the dialogue with the patients. This feedback phase provided the final iterations, and among other things, led to a simplification of the graphs. Furthermore, the requested elements (a note-system and an open dialogue box) were established.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the design and usability of the HeartPortal. The HeartPortal was developed in a three-phase process based upon PD. Our findings show that HF patients and HCP had an overall positive experience using the web portal and that end-users’ needs and ideas have been integrated into the portal.

Based on our questionnaire data, the HCP were a little less satisfied with the web portal compared to the patients. This might be explained by the fact that HCP tended to answer not from their own point of view, as end-users, but in terms of the best outcome for the patients. Therefore, we believe that the HCP perceive the patients as being more seriously ill and less at ease ill at ease with the HeartPortal than is actually the case. The patients seemed to be very satisfied with the web portal, which we consider to be the most important finding of this study. Even though the patients experienced the HeartPortal positively, they used more time on solving the tasks than did the HCP. This is hardly surprising, as the patients were also less familiar with this kind of technology compared to the HCP, who use digital technology in their everyday work. The patients’ lack of routine experience may explain their need for more time to navigate the HeartPortal than the HCP. Several other studies (7,8,21,30,31) have also found eHealth web portals to be viewed by users as a positive experience and satisfaction, results which underpin our findings.

The HeartPortal design has been based upon theories highlighting the need to establish and maintain motivation for long-term health behavior change. SDT states that autonomy, competency and relatedness are basic needs that must be fulfilled in order for people to attain intrinsic motivation (16,17), which, contrary to extrinsic motivation, is self-sustaining. Our study sought to explore whether the HeartPortal, as a central part of the Future Patient Telerehabilitation Program could improve patients’ ability to manage their own disease so as to avoid re-hospitalization, stimulate and strengthen interaction among patients, relatives, and HCP during the patient´s rehabilitation process and increase patients’ quality of life, as has been seen in other studies (32,33). Furthermore, a review by Dinesen et al. (34) indicated that eHealth web portals may be used for online patient education and to improve the patient’s self-management of their disease.

Using a PD approach in designing and evaluating the HeartPortal resulted in patients’ overall satisfaction and positive experience in the usability tests. The HeartPortal proved to be both appropriate and well-functioning in meeting users’ needs. Other studies (5,7,10) support these findings of the benefits of PD for designing interactive web portals such as the HeartPortal. For example, in their practical guidelines and suggestions for development of eHealth web portals, Darlow and Wen (11) underscored the importance of addressing the needs and experiences of patients in designing and evaluating users’ satisfaction with the use of the web portal. In another study, Bjerkan et al. (10), explored how PD contributed to the design of an electronic care plan in Norway. They found that an iterative process of development, which we also applied to the development of the HeartPortal, resulted in improvements in meeting end-users’ needs and requests. Bjerkan et al. (10) emphasized that PD is necessary for constructive collaboration between developers and participants. They also found that the participants contributed insights that added new features to the web portal. Other studies (5,7) directly recommend the adoption of user-centered approaches and PD.

Limitations of this study

The participants who have evaluated the HeartPortal were new users. If the participants had used the portal for a longer period, the results might have been different; they might have discovered either additional benefits or encountered more difficulties. Another limitation of this study is that patients’ relatives did not participate in the evaluation of the portal, but only in the portal’s initial design.

Conclusions

Based upon a PD process, an interactive HeartPortal for use by HF patients within the Future Patient Telerehabilitation Program was designed and developed. Evaluation of the portal by patients and HCP showed that the design and structure of the HeartPortal was viewed as logical and easy to navigate. The study confirmed the crucial importance of PD in developing web-based technologies for patient users. Effective eHealth solutions will become problematic unless we can involve and listen to the patients and then integrate their needs and competencies into our designs. The HeartPortal will now be tested in a clinical trial in the Future Patient Telerehabilitation Program.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the HF patients, their relatives, and healthcare professionals for participating in this study. We also wish to thank the healthcare professionals at the healthcare centers in Skive, Viborg and Randers, and in the Cardiology Departments at the Regional Hospitals of Viborg and Skive for their cooperation. We also express our thanks to the Aage and Johanne Louis-Hansen’s Foundation for making this study possible. For more information about the Future Patient project, see http://www.labwellfaretech.com/fp/heartfailure/. The Future Patient project is financed by the Aage and Johanne-Louis Hansen’s Foundation, Aalborg University and with co-financing from all partners in the project. The project partners are: Healthcare centers in Viborg, Skive, and Randers; the Cardiology Wards at the Regional Hospitals in Viborg and Skive; Danish Heart Association; Viewcare; Technical University of Denmark; Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Aarhus University; Department of Computer Science, Aalborg University; Laboratory of Welfare Technologies-Telehealth & Telerehabilitation, Department of Health Science and Technologies, Aalborg University.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee (N-20160055), Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03388918). All participants signed an informed consent form.

References

- Ghisi GL de M. A systematic review of patient education in cardiac patients: Do they increase knowledge and promote health behavior change? Patient Educ Couns 2014;95:160-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med 2004;116:682-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen CB, Hansen J, Spindler H, et al. Heart patients’ experiences and use of social media in their rehabilitation: A qualitative study. In: Bellika G, Bygholm A, Dencker M, et al. editors. Scandinavian Conference on Health Informatics 2013 2013:51-4.

- Nguyen HQ, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Rankin SH, et al. Supporting Cardiac Recovery Through eHealth Technology. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;19:200-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cnossen IC, van Uden-Kraan CF, Eerenstein SEJ, et al. A Participatory Design Approach to Develop a Web-Based Self-Care Program Supporting Early Rehabilitation among Patients after Total Laryngectomy. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2015;67:193-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clemensen J, Rothmann MJ, Smith AC, et al. Participatory design methods in telemedicine research. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:780-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolpin SE, Lober W, Halpenny B, et al. Development and usability testing of a web-based cancer symptom and quality-of-life support intervention. Health Informatics J 2015;21:10-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byczkowski TL, Munafo JK, Britto MT. Family perceptions of the usability and value of chronic disease web-based patient portals. Health Informatics J 2014;20:151-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maguire M. Methods to support human-centred design. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2001;55:587-634. [Crossref]

- Bjerkan J, Hedlund M, Helleso R. Patients’ contribution to the development of a web-based plan for integrated care-A participatory design study. Inform Health Soc Care 2015;40:167-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Darlow S, Wen KY. Development testing of mobile health interventions for cancer patient self-management: A review. Health Informatics J 2016;22:633-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dinesen B. Future Patient. Laboratory for welfare technology - telehealth and telerehabilitation [Internet] 2017. Available online: http://www.labwellfaretech.com/fp/heartfailure/?lang=en

- Kensing F, Simonsen J, Bødker K. MUST: A Method for Participatory Design. Human-Computer Interact 1998;13:167-98. [Crossref]

- Leth S, Hansen J, Nielsen OW, et al. Evaluation of commercial self-monitoring devices for clinical purposes: Results from the future patient trial, phase I. Sensors (Basel) 2017;17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, et al. The person-based approach to intervention development: Application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beatty AL, Fukuoka Y, Whooley MA. Using Mobile Technology for Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Review and Framework for Development and Evaluation. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000568. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thorup CB, Grankjaer M, Spindler H, et al. Pedometer use and self-determined motivation for walking in a cardiac telerehabilitation program: a qualitative study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2016;8:24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryan RM, Patrick H, Deci EL, et al. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on Self-Determination Theory. Eur Heal Psychol 2008;10:2-5.

- Matsuoka S, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Kayane T, et al. Health literacy is independently associated with self-care behavior in patients with heart failure. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1026-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moser DK, Robinson S, Biddle MJ, et al. Health Literacy Predicts Morbidity and Mortality in Rural Patients with Heart Failure. J Card Fail 2015;21:612-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xie B. Effects of an eHealth literacy intervention for older adults. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaver B, Dunne T, Pacenti E. Design: Cultural probes. Interactions 1999;6:21-9. [Crossref]

- Gaver WW, Boucher A, Pennington S, et al. Cultural probes and the value of uncertainty. Interactions 2004;11:53. [Crossref]

- Macefield R. How To Specify the Participant Group Size for Usability Studies: A Practitioner’s Guide. J Usability Stud 2009;5:34-45.

- Dinesen B, Spindler H. Individualized telerehabilitation for heart patients across municipalities, hospitals and medical disciplines: preliminary findings from the Teledialog project. Int J Integr Care 2014;14. [Crossref]

- Krogstrup HK, Kristiansen S. Deltagende observation 2nd ed. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzel, 2015.

- Brinkmann S. Qualitative inquiry in everyday life. London: SAGE, 2012.

- Spiegel R. Sleep and sleeplessness in advanced age. New York: MTP Press Ltd., 1981.

- Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, et al. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City cardiomyopathy questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1245-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nahm ES, Blum K, Scharf B, et al. Exploration of patients’ readiness for an ehealth management program for chronic heart failure: A preliminary study. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2008;23:463-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lind L, Karlsson D. Telehealth for “the Digital Illiterate”-Elderly Heart Failure Patients Experiences. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014;205:353-7. [PubMed]

- Wiggers AM, Peek N, Kraaijenhagen R, et al. Determinants of Eligibility and Use of Ehealth for Cardiac Rehabilitation Patients: Preliminary Results. In: Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2014:818-22.

- Baker DW, DeWalt DA, Schillinger D, et al. The Effect of Progressive, Reinforcing Telephone Education and Counseling Versus Brief Educational Intervention on Knowledge, Self-Care Behaviors and Heart Failure Symptoms. J Card Fail 2011;17:789-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dinesen B, Nonnecke B, Lindeman D, et al. Personalized Telehealth in the Future: A Global Research Agenda. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Joensson K, Melholt C, Hansen J, Leth S, Spindler H, Olsen MV, Dinesen B. Listening to the patients: using participatory design in the development of a cardiac telerehabilitation web portal. mHealth 2019;5:33.