Telepsychiatry and integrated primary care: setting expectations and creating an effective process for success

Introduction

Mental illness is the leading cause of disability worldwide, accounting for 21% of the global burden of disease in terms of years lived with disability (1,2). However, two-thirds of primary care providers in the United States report they are unable to get their patients into outpatient mental health services (3). Obstacles to accessing quality psychiatric care include specialist shortages, stigma, and restrictions on insurance coverage (4,5). One solution to address these challenges is the use of integrated and collaborative health-care models that seek to incorporate diverse mental health specialties, including psychiatry, into primary care settings (6-8). For convenience and practicality, primary care clinics are increasingly interested in utilizing telepsychiatry services as part of their integrated model. Telepsychiatry is a subset of telemedicine that delivers psychiatric assessment and care through telecommunications in the form of live interactive video conferencing supported by other technologies such as e-mail, electronic health records, and patient portals (9,10). These communication channels allow primary care providers and their patients quick, reliable and consistent access to psychiatric expertise.

While offering many benefits for providers and patients, integrated telepsychiatry can be a complex intervention with unique challenges. Several processes involving operations, workflow, logistics, technology, reimbursement strategies, and care coordination are essential to the sustainability of integrated telepsychiatry models (11,12). This article highlights processes around interprofessional care coordination from a telepsychiatry perspective and acknowledges that remote telepsychiatry relationships can amplify the inherent complexities of integrated care (13). Inter-professional collaboration is most successful when clinicians have a shared sense of belonging to a team (14).The day-to-day informal interactions among professionals that contribute to positive teamwork, trust and rapport building are more difficult to initiate and sustain via telepsychiatry relationships due to further restrictions on time, asynchronous activities, and the loss of non-verbal cues. These gaps must be considered and addressed when telepsychiatry relationships and processes are established.

An integrated telepsychiatry service can take many forms. We illustrate the model used at The University of Colorado School of Medicine’s Helen and Arthur E. Johnson Depression Center to provide context for our recommendations. This program utilizes a stepped integrated telepsychiatry consultation model that includes e-consults over a shared electronic medical record (EMR), provider-to-provider consults, and provider-to-patient consults over a secure live interactive video conferencing platform (15). Through a multi-stage and iterative process participating psychiatrists have over the course of several years learned a great deal concerning how to better coordinate care with their primary care colleagues (13).

Successful collaboration over virtual platforms requires both primary care teams and psychiatrists using telepsychiatry to modify their usual practices. When working together over virtual spaces, it becomes imperative to have upfront conversations that set clear expectations around how providers can work best together. Adding to best practices in the literature, we offer suggestions and lessons learned at the University of Colorado for developing a formal set of expectations and procedures that creates effective team interactions (16). These expectations concern what telepsychiatry consultants can (and can’t) provide, information primary care teams can collect to facilitate the efficiency of psychiatric consultations, how primary care teams can formulate effective consultation questions, and how primary care teams can modify practices to optimize the use of telepsychiatry.

Definition of terms: primary care, telepsychiatrist, consultation

We recognize that primary care settings vary greatly regarding the number and types of physicians, non-physicians, other health providers, behavioral health providers, and support staff available (17). In order to be inclusive and accommodating, we denote the terms primary care provider (PCP) and primary care team to reflect the diversity of embedded clinicians and non-clinicians on-site in any given primary care setting. The term consultation throughout this paper is used to describe a shared and ongoing collaborative process regarding care coordination affecting both psychiatric medication management and psychosocial interventions. The terms telepsychiatrist and psychiatric consultant include both physician psychiatrists and non-physician psychiatric nurse practitioners.

Literature review

Since the World Health Organization first discussed the value of inter-professional collaboration for improving patient outcomes, successful collaboration between primary care and mental health providers has improved outcomes for both depressed and anxious patients (18). Studies have identified broad directives that include creating a non-hierarchical team with unified vision, clear roles, and flexibility to help guide collaborative care initiatives and implementation (14,19). A Canadian study by Sunderji and colleagues (14) identified core competencies for psychiatric clinicians working in integrated care models and found that integrated teams were best supported by teamwork occurring across disciplines that also transcended traditional hierarchies. This type of teamwork in turn supported a collaborative environment open to knowledge exchange regardless of rank. Here, primary care and psychiatric team members each brings their unique knowledge of the patient’s history, situation, and social and medical contexts, and their particular set of interpersonal and clinical skills to the group; decisions regarding who should undertake which specific elements of care (information gathering, diagnosing, treatment planning, indirect consultation, and treatment administration) are made regardless of rank on a case by case basis to take advantage of available resources.

Developing effective collaborative telepsychiatry care requires frequent multidisciplinary interactions and ongoing engagement (20). In a pilot study focusing on primary care management of complex mental health conditions, notably, bipolar disorder, Kern and Cerimele (21) identified that the psychiatric clinician needed to work collaboratively and flexibly across disciplines, often serving primarily in a consultative role, usually seeing patients directly only infrequently (either in person or via telepsychiatry). These arrangements required the psychiatric clinician to provide supervision, education and support of multiple members of the team to help them appropriately identify and monitor patients in the primary care context. Although conducted in a safety-net clinic, where both medical and psychiatric clinicians may have been more accepting of a flexible model of care than might be the case elsewhere, this study nonetheless highlights the diversity of support that a psychiatrist can offer in caring for patients with psychiatric illness in their medical home (21).

In a review of 50 e-consults for psychiatry (40% for depression) requested by primary care providers throughout 8 primary care sites in an urban academic medical center with a diverse payer mix, Lowenstein et al. (22) found that the consulting psychiatric clinician commented on the diagnosis in 60% of cases and offered management strategies in 100% of the cases. In turn, the PCPs followed consultants’ recommendations in 76% of the cases. The process employed PCP completed templates for referral which outlined the clinical question, the relevant history, and any diagnostics used. Following review by a psychiatrist, a subset of these patients (26%) was referred for an in-person appointment with the psychiatric clinician. The authors reported that this model improved access, especially for vulnerable and non-Native English speakers, but they were not able to clearly delineate quality or efficacy of e-consults compared to traditional referrals.

In a recent article, Shore (16) suggested best practices in team-based telepsychiatry across models and settings. Overall recommendations included: (I) attending to team composition and culture, balancing between remotely located team members and those located at the patient site; (II) creating clear team communication processes with an iterative approach to continuous improvement; and (III) assuring that the psychiatric clinician provides a robust, egalitarian, and supportive leadership style attending to all relationships among team members.

The above articles elaborate on a variety of integrated models, highlighting the importance of interprofessional care coordination, and provide broad recommendations for addressing the added complexity of virtual models. Building on this literature, we outline an implementation process and offer lessons learned from an integrated telepsychiatrist perspective to enhance virtual inter-professional teamwork. We recognize the fundamental importance of provider expectations for delineating clear care coordination and advocate that careful attention to how providers with different training and expertise work best together is essential to successful telepsychiatry efforts. At the University of Colorado, we learned not to assume that primary care providers and psychiatrists fully understand each other’s expertise or that they implicitly know how to best work together to improve patient care. Successful implementation of telepsychiatry-enabled integrated care services requires an upfront investment of time by providers and openness to adaptability in order to develop unified strategies and adequate rapport for smooth patient interactions. We propose a formal “Go Live” implementation planning process that allows for critical discussion between inter-disciplinary providers, identifies implicit assumptions, and aligns expectations. Additionally, we offer recommendations on how communication style and clinical protocols can be modified, providing examples of effective tools that further leverage technology for ongoing communication.

How to best utilize a telepsychiatry consultant—what can primary care expect?

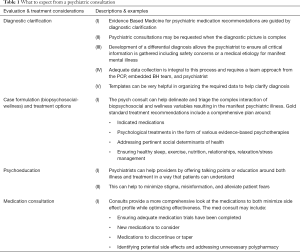

Our experience suggests several ways in which the psychiatric consultant can work with the primary care team including diagnostic clarification and case formulation, psychoeducation, and medication consultation. It is critical upfront to clarify the primary care team’s expectations about what psychiatric consultation and collaboration can and will provide. Table 1 offers guidance for helping primary care teams identify and take full advantage of telepsychiatry services for patient care while alleviating their own workloads.

Full table

Aligning on diagnostic clarification and case formulation

The most effective use of psychiatric expertise in primary care begins with diagnostic confirmation, clarification, or at minimum a thoughtful and agreed upon working diagnosis. Misdiagnosis, both under- and over-diagnosis, commonly occurs in the care of patients struggling with mental illness, and both can lead to suboptimal treatment (23-28). Following initial treatment failure, American Psychiatric Association (APA) Guidelines recognize the critical importance of reconfirming the diagnosis prior to further treatment planning (29,30), and developing an optimum treatment plan requires accurate understanding of what is being treated. In our experience, primary care providers often request psychiatric consults after an initial failed or inadequate treatment trial, generating timely opportunities to work with a psychiatric consultant to re-evaluate the patient’s differential diagnosis and case formulation.

However, primary care teams may not specifically ask for diagnostic clarification or case formulation. Indeed, most clinical questions posed by primary care providers focus on how to manage medications (13). In Lowenstein et al.’s 2017 survey (22), 98% of the e-consult requests from primary care providers asked about medications (76% regarding medication choices and 32% regarding side effects and interactions) whereas only 4% asked for consultation on diagnosis. Despite this, 60% of the responses by the psychiatric consultants addressed diagnostic considerations and/or asked for additional history and diagnostic testing, underscoring potentially common discrepancies between how psychiatric and primary care providers practice.

As in all specialties, the purpose of diligently developing a differential diagnosis in psychiatry is to ensure that treatment is informed by a clear understanding of the condition. For example, “depression” is ubiquitous in primary care. Consider a new patient who describes himself as feeling “depressed”. A busy PCP might, therefore, be quick to assess this patient as suffering from a depressive disorder and prescribe an antidepressant medication. However, symptoms of “depression” may be only part of this patient’s difficulties, and not necessarily the most important ones. If a depressive disorder is suggested or diagnosed too quickly, this patient may not be as forthcoming about other symptoms he may be experiencing such as soft psychotic symptoms, excessive alcohol use, misuse of street or prescription drugs, reliance on food banks, nightmares, self-harm, or the recent discovery of an extra-marital affair. The same patient may not realize that he is experiencing sedating side effects due to propranolol or that he might be developing a brain-affecting auto-immune disease. All these additional findings would clearly alter differential diagnosis and formulation, with clear implications for treatment.

Our tele-psychiatry service also receives many requests from PCPs asking for medication options for patients with “depression” who have already been tried on antidepressant medications but remain symptomatic. These instances offer perfect opportunities for psychiatrists to model how psychiatry thinks about the heterogeneity of depression, asking critical questions that differentiate specific mood and other psychiatric disorders, as well as characterize their severity, etiology, and comorbidities among many other factors. For example, we received a consult concerning a 59-year old male with a previous history of major depressive disorder (MDD) who achieved remission on Venlafaxine 225 mg many years ago but who recently re-presented with return of “depression”. Because he had been tried on several antidepressants in the past with either significant adverse effects or lack of efficacy, we were asked for additional medication options. Upon further questioning during our evaluation, we learned that the patient’s father had passed away a few months ago, the patient was feeling resentment and guilt due to their fractured relationship, and that he recently increased his alcohol use to 3–4 drinks every day to manage these difficult feelings. While this patient has clear risk for a recurrent MDD episode, and it is obviously important to consider medications, the ultimate focus of his treatment was on grief counseling, psychotherapy, and cessation of alcohol use.

These examples illustrate that “depression” does not constitute an illness. Rather, feeling depressed is a symptom, analogous to fever, as a cardinal but non-specific indicator of distress or dysregulation since it can manifest from large numbers of underlying mechanisms and etiologies. A psychiatric consultant will elaborate on the full constellation of signs and symptoms while assessing clinical significance, duration, and intensity to determine if a patient has the “illness” of major depressive disorder (MDD) (31). Even if a patient meets criteria for MDD, a medication may not be the primary recommendation. Additional characteristics such as severity, recurrence, suicidal risk, presence of psychosis, and associated co-morbid and external environmental conditions will determine whether it is within standard of care to initiate a trial of psychotherapy alone or whether biologic treatments are indicated (29).

To illustrate another common challenge in primary care, patients who are not always attuned to their own feelings can misattribute symptoms, leading to under-diagnosis of depressive illness. For example, we received a consult request for a 42-yo female patient who presented with concentration difficulty resulting in falling behind at work, and who reported a past diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with previous improvement on lisdexamfetamine. We were asked to evaluate for ADHD and provide medication options. On evaluation, she met full criteria for MDD with three past recurrent episodes, struggled with sleep onset insomnia, and described a significant trauma history involving domestic violence. We educated the patient that concentration difficulties constitute a hallmark symptom of MDD. Additionally, we noted that insomnia and a potential PTSD diagnosis may also contribute to concentration difficulty. We explained that although she might have comorbid ADHD and that we were happy to continue her evaluation, we recommend initially prioritizing further clarification and treatment for depression and possible post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Another example in which psychiatric consultants can help clarify complicated diagnoses concerns differentiating bipolar spectrum from other mood-related disorders in depressed patients with “mood swings.” Some patients who endorse manic symptoms on mood-related screening tools, do not, on closer examination, meet criteria for mania based on specified duration, distress, or impairment. Similarly, hypomanic episodes, mixed symptoms, and mood lability are easily confused or overlooked. For example, we received a consultation request for a 39-yo female presumed to have bipolar disorder who was prescribed quetiapine (Seroquel) 300 mg PO QHS for low mood and anxiety. The PCP was a family medicine resident who wanted guidance on medication options. After comprehensive evaluation we discovered that the patient’s presumed manic-like symptoms occurred only once as a teenager when she used methamphetamines. We were able to inform both the patient and her PCP that she did not have a bipolar affective disorder and could be tapered off quetiapine (a medication with risk for severe metabolic side effects). While she did meet criteria for mild generalized anxiety disorder, these anxiety symptoms were confounded and exacerbated by the stressful social circumstances of being a single mom with 3 children under the age of 5, and limited financial resources. We involved our embedded social worker to obtain assistance for her childcare needs and discussed other treatment options including psychotherapy and more appropriate medications.

Taking full advantage of biopsychosocial conceptualization

As with our primary care colleagues, psychiatrists recognize and consider the full range of intersecting biologic, psychologic and social variables that affect patient health and specifically cause mental illness, resulting in a DSM 5 diagnosis (31). This includes attention to general wellness factors fundamental to mental health such as sleep, exercise, nutrition, relationships, and stress management. Further complicating the picture and influencing treatment decisions are an array of subjective variables such as patient preferences, readiness to change and engage in treatment, feelings of shame and stigma, personal understanding about one’s psychiatric conditions, and family or social support. We recommend utilizing psychiatric consultation to assess and prioritize these multiple, sometimes competing, factors to help formulate effective patient-centered stepwise plans.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation, which constitutes a key aspect of the consultant’s role, can help patients better contend with labels, stigma, and distorted facts they hear from the media, friends, family or their community. The psychiatric consultant can model how to best interact with and educate patients to describe and discuss diagnoses, case formulations and treatments. These demonstrations can show primary care providers how they themselves might better utilize stigma-alleviating strategies to educate their patients.

Medication management

Psychotropic medication consultation aims to optimize medication regimens, offering greatest symptom relief with fewest adverse effects. Psychiatrists are often asked to see patients after multiple failed medication trials and/or to manage patients whose psychiatric medication lists have evolved into complex blends of polypharmacy. Patients often don’t understand the indications for their various medications, contributing to non-adherence or incorrect self-dosing. Minimizing the number of medications and simplifying dosing regimens can reduce this confusion and promote better adherence. In our program’s collaborative care model, our PCPs have asked us to initiate all recommended psychopharmacologic changes within the patient visit; accordingly, we discuss treatment options with patients, obtain consent, and initiate tapers or new prescriptions and then document a follow-up plan for primary care to execute. An important exception, related to the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008, which imposes rules concerning prescription of controlled substances via telepsychiatry (32), is that we cannot prescribe controlled substances including benzodiazepines and stimulants because we do not have an initial in-person encounter with the patient. These important restrictions, as well as all other federal, state and organizational laws and policies concerning the prescription of controlled substances, must be clearly understood by all primary care and psychiatric providers collaborating via telepsychiatry.

How to most efficiently utilize a telepsychiatry consultant—what does the psychiatric consultant need from primary care providers to provide the best service?

The PCP is critical for identifying, selecting and triaging patients who are appropriate for telepsychiatry consultation, framing cogent consultation questions, and presenting sufficient background information to orient the psychiatrist to the patient’s most pressing issues.

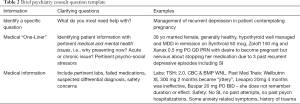

Patient presentation

Presenting a patient for psychiatric consultation begins with a “one liner” that includes identifying patient demographics, pertinent medical concerns, explanations for why the patient is presenting at this particular point in time, at whose behest (patient, family member, others), and whether the problems are of new onset, an acute exacerbation of a chronic condition, or chronic and stable. The primary care provider should also be prepared to supply additional information, such as pertinent psychiatric symptoms, suspected diagnoses, timing and onset of illness, the patient’s longitudinal course, and pertinent psychosocial factors. Table 2 presents a brief template, and a good starting point, to guide psychiatric consultation questions and to prompt primary care teams on basic information to gather prior to making a request.

Full table

Specific questions

Providers are likely to be comfortable with in-person medical consultation models which allow for informal discussions through which the consultee and consultant can tease out underlying concerns, refine questions and strategies, and then bring their consensus understanding and planning to bear when they see their mutual patients, sometimes concurrently. In contrast, consultations via telehealth technologies frequently involve asynchronous communications such as email, requiring more structured processes to avoid miscommunication. Consultation time can be most effectively used when PCPs formulate specific questions for the consultant and identify immediate concerns.

Asking good psychiatric questions is not always intuitive or obvious. Patients with complex mental illnesses and social situations can be overwhelming, especially in short PCP visits of about 20 minutes. When our telepsychiatry service first began, it was not uncommon to have a referral placed without any question or only a vague question regarding medication options (e.g., “psych consult please” or “medications for this patient’s depression?”). Sometimes the psychiatric consultant identified many issues or diagnoses, each carrying the potential for many medication options but had to independently determine what might be most helpful to the patient at that time while best supporting the primary care team. Without knowing what specific questions the PCP might have in mind, psychiatric consultants do not always meet the PCP’s immediate needs. For example, a PCP might have already known that a patient failed, or had significant adverse reactions to, or had other objections to taking a number of previous psychiatric medications but may not have communicated this to the psychiatric consultant. Without this information at hand the consultant might ineffectively use time with incorrect leads or make less useful suggestions. Such poor communication can rupture the PCP-psychiatrist connections necessary for successful integrated telepsychiatry programs which, ultimately, are intended to provide primary care clinicians enough support and guidance to feel comfortable managing and treating a broader range of psychiatric illness than would otherwise be possible. In this light, we strongly recommend that primary care providers thoughtfully formulate specific consultation questions, considering them to be starting points around which all providers can work together.

Notably, the PCP who has an established relationship with the patient can provide the consultant with critical background information. A clear PCP consultation question might state: “Patient is contemplative about alcohol cessation and we have discussed the effects of alcohol on depression. While it would be helpful for psychiatry to briefly reaffirm the importance of and options for managing alcohol use, we are looking for specific help around diagnostic clarity and treatment options for his comorbid depression.”

It is appropriate, advised and encouraged for PCPs to ask consultants questions pertaining to a wide breadth of symptoms, diagnoses, and treatment options. Questions may inquire about why specific patients might be struggling with treatment adherence or about concerning behaviors that impact the provider-patient relationship, such as why a certain patient always presents in crisis. Since primary care providers can feel both professionally and personally challenged by complex psychiatric patients, especially given the limited time for visits allotted in primary care, it is perfectly acceptable and reasonable for a PCP to admit these difficulties. For example, questions might include: “I could use help figuring out how to think about this patient to help formulate a mental health treatment plan” or “I’m having trouble with this patient because I never have enough time and feel overwhelmed.” These types of request are actually very helpful for letting the psychiatrists know where to focus, recognizing telepsychiatry as a service for the provider as well as for the patient (33).

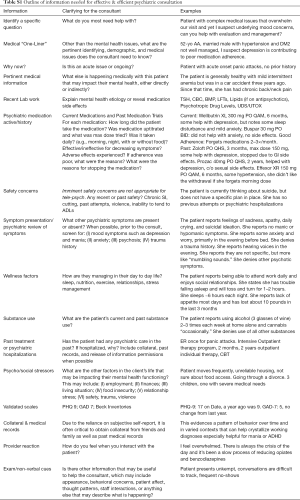

Data collection: utilizing the entire behavioral health team

Telepsychiatry consultants need sufficient information to assure that they don’t miss critical issues such as acute safety concerns, so they can reasonably avoid doing harm, and can comfortably suggest feasible evidence-based next steps concerning diagnostic clarification and treatment options. Given time constraints, psychiatrists rely on the primary care team for essential data collection, both before and during telepsychiatry patient contact visits.

However, the psychiatric consultant must also be aware to not overly burden the primary care team with excessive data collection requests. Skilled consultants recognize that PCP time is highly limited, and that PCPs vary widely with interest, comfort, and expertise with mental health issues. Therefore, in any given service setting, it is important to clarify what elements of data are essential and expected and who (the primary care team or psychiatric consultants) will be responsible for collecting this data. For example, psychiatric consultants may benefit from knowing information about patients that most PCPs are likely to sensitively intuit but may not typically document, including non-verbal aspects of the exam such as appearance, facial expressions, body posture, behavior, emotional reactions, and overall patient affect, and thought content. Data unique to psychiatry can also include the provider’s emotional reactions to the patient, which often give important clues into patient psychodynamics and personality traits. This type of information can only be communicated verbally. When feasible, we recommend utilizing behavioral health providers or other designated staff embedded in primary care practices to help collect data including non-verbal cues, psycho-social context, psychiatric review of symptoms, validated mental health screening tools, collateral information, past records, and release of information permissions. Having standardized office procedures for gathering and collecting this information in anticipation of telepsychiatry consultations will ease the work burden. When first establishing telepsychiatry programs and relationships, planning should clarify and assure that time and finances are appropriately allotted to sustainably support activities to accomplish these tasks within specific clinical workflows.

Formalizing the process: leveraging technology through the use of templates

We recommend that telepsychiatry services utilize formal templates and workflow processes that prompt collecting and organizing information required for telepsychiatry consultations. To develop these systems, we initially created a simple template to serve as a communication tool (see Table 2), with the expectation that a PCP would use this brief prompt as a starting point for communicating with the telepsychiatry consultant (either in email, EMR messaging, or embedded in the referral order). In turn, the psychiatrist would respond with clarifying questions either about diagnosis or past treatment trials, perhaps initiating a brief exchange before providing recommendations. This system worked well on a small scale when a limited number of providers and patients were involved.

As the telepsychiatry services expanded to cover larger numbers of patients, providers, and clinics, more robust templates were required. Table S1 in Supplementary materials was created to provide all team members with clear and explicit details and examples of the types of data that facilitate effective psychiatric consultations. We recommend that PCP teams use this table as a tool to design their own templates and to help determine which team members will be responsible for collecting and documenting each element of information. Where possible, we also recommend embedding these templates in EMRs that can automatically populate data from the historical chart.

Full table

Because of the frequency with which psychiatric medication management questions are posed to psychiatric consultants, we urge special attention to templating data collection on past medication trials. Where possible, we suggest that in addition to containing basic lists of past psychiatric medication prescriptions templates also note for each medication whether the patient had adequate trials (including information on the duration, dose, and daily adherence). Noting prior responses and adverse effects for each medication may help clarify diagnoses and guide future medication decisions. For example, depressed patients who become agitated or activated in response to an SSRI may be showing indications of possible bipolar disorder. Similarly, patients might have taken medications for only a few days, never received optimized doses, stopped taking medications for judicious (or capricious reasons), and potentially misattributed side effects. This information is difficult to pull from medical records but use of a template can help PCPs provide information along these lines that can help consultants make optimal medication recommendations (see Table S1).

Additional considerations

Access and timing

Having timely and reliable access to psychiatric consultation is critical to providing good service. We recommend developing systems of care that give PCPs access to psychiatric consultation at any and all steps along the continuum of potential services. As our programs have expanded to more primary care clinics, we have increasingly encouraged sequential use of our services to allow greater overall access to consultation. Our e-consultation service (via email) is intended to be used for non-urgent matters and has an expectation of 3–5 business days for response. Once we move to evaluating a patient via video-conferencing, we set an expectation for about 1–3 scheduled visits for each patient, to allow for assessment, diagnostic clarification, psychoeducation, consideration of treatment options, and treatment initiation. We also expect further follow-up communication, generally over e-consult or by provider to provider consult (usually telephone), to briefly discuss ongoing implementation and results of the treatment plan.

Patient expectation

At the start of telepsychiatry examinations patients should be clearly informed that this service provides only a consultation, with an estimated 1–3 telepsychiatry visits, in collaboration with the primary care team who remains the patient’s point of contact. This service does not establish an ongoing doctor-patient relationship between the patient and psychiatrist. Rather, the primary care team will maintain the established patient relationship and be responsible for ongoing treatment and management including prescriptions, medication concerns, follow-up, and coordination.

What is not appropriate for telepsychiatry and/or primary care?

Each provider team decides on the illnesses and severity levels that they are comfortable treating in their primary setting. These decisions should be considered within the context of the PCP team’s willingness, capacity, and resources to support a telepsychiatry service. Some models of integrated care telepsychiatry have strict limits on access to and levels of involvement of a telepsychiatry provider. In the University of Colorado model, we see a tremendous range of disorders and problems, including patients with severe mental illness and patients who present with clear indications for treatment in specialty settings. If establishing a patient with ongoing outpatient psychiatric services is indicated, we utilize the telepsychiatry consult service to help bridge care. Some of these patients choose to still receive ongoing care from their PCP, often due to comfort level or continued access issues.

While acknowledging that the telepsychiatry consultation might not provide sufficient treatment, most of the time the psychiatric consultant can offer something useful to these patients from validating the indication to establish care, providing education, and providing brief motivational interviewing to offering potential resources and treatment options. Ultimately, the PCP makes the decision regarding continuation of treatment for each patient.

In general, acute psychiatric emergencies are not appropriate for integrated care telepsychiatry services. However, since patient emergencies may arise during a telepsychiatry patient visit, it is critical to have formal procedures in place to handle emergency situations, drawing from existing in-person procedures. Management of emergencies via telepsychiatry requires clear expectations concerning how to mobilize the embedded providers and staff to call security and/or police, secure the physical office and clinic space, potentially complete a mental health hold (involuntary hospitalization for assessment, management and safety), and coordinate emergent transport to an emergency department as needed. Guidelines have been published concerning the management of psychiatric emergencies in telepsychiatry service settings (34-36).

Difficulties for the traditional psychiatrist

Although education and training in the provision of telepsychiatry services is not yet widely available in psychiatric residency programs, the popularity and appeal of such training is increasing. Traditional psychiatric training revolves around the unique doctor-patient relationship in which psychiatrists schedule long sessions over long periods of time with each patient, collecting large amounts of information. Such models run counter to the demands of busy primary care practices. In contrast, telepsychiatry consultants are expected to quickly gather and evaluate only the most pertinent data necessary for deciding about a few clear next steps in treatment. These practice demands require that PCPs and their consulting psychiatrists clarify their expectations and, in turn, determine how flexible they can become in modifying their usual clinical practices. To train psychiatric residents to meet rapidly expanding demands for integrated primary healthcare telepsychiatry services, we must first develop cadres of psychiatric faculty role models who have attained facility and comfort in conducting these services.

Conclusions

Telepsychiatry consultations offer practical ways to address mental health workforce shortages and provide quality psychiatric care within primary care clinics. As telepsychiatry services becomes more commonly available, increasing numbers of providers will want to benefit from being able to use these consultations most efficiently and effectively.

The recommendations we have offered are heavily drawn from lessons learned in our evolving programs over time. We have learned that setting explicit expectations for each participant’s role and contribution is key. Primary care clinics opting to use telepsychiatry consults may need specific procedures, processes, and training to help them gather data and implement care differently than in more traditional face-to-face settings. Clearly defined and articulated consultation questions and needs, use of specific templates, and review of data prior to seeking the consultation can help practices go smoothly. When initiating telepsychiatry consultation programs, PCP teams may want to implement routine and scheduled discussions for didactics, trainings, handouts, and article reviews to help the team grow comfortable and competent with their processes.

To assure quality, these processes need to be iterative as well. All parties need to understand what is or isn’t working and revising and reworking accordingly in an atmosphere of flexibility, shared learning, and willingness to try new things. As research in this area continues to grow and additional lessons are learned in practice settings, further refinements of best practices will evolve. For the present, we hope that the recommendations offered here can assist integrated primary care teams develop telepsychiatry consultation programs that benefit both patients and their providers.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2020.02.01). JHS reports other from Access Care, other from American Psychiatric Association Press, other from Springer Press Inc, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:171-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;382:1575-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cunningham PJ. Beyond Parity: Primary Care Physicians’ Perspectives On Access To Mental Health Care: More PCPs have trouble obtaining mental health services for their patients than have problems getting other specialty services. Health Affairs 2009;28:w490-501. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rowan K, McAlpine DD, Blewett LA. Access And Cost Barriers To Mental Health Care, By Insurance Status, 1999-2010. Health Affairs 2013;32:1723-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker ER, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, et al. Insurance Status, Use of Mental Health Services, and Unmet Need for Mental Health Care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:578-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bower P, Gilbody S. Managing common mental health disorders in primary care: conceptual models and evidence base. BMJ 2005;330:839-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:1109-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crowley RA, Kirschner N. The Integration of Care for Mental Health, Substance Abuse, and Other Behavioral Health Conditions into Primary Care: Executive Summary of an American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:298. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adaji A, Fortney J. Telepsychiatry in Integrated Care Settings. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2017;15:257-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hilty DM, Rabinowitz T, McCarron RM, et al. An Update on Telepsychiatry and How It Can Leverage Collaborative, Stepped, and Integrated Services to Primary Care. Psychosomatics 2018;59:227-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Turner EE, et al. Telepsychiatry integration of mental health services into rural primary care settings. Int Rev Psychiatry 2015;27:525-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waugh M, Voyles D, Shore JH, et al. Telehealth in an Integrated Care Environment. In: Feinstein RE, Connelly JV, Feinstein MS, editors. Psychiatry, primary care, and medical specialties: pathways for integrated care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Working Party Group on Integrated Behavioral Healthcare, Baird M, Blount A, et al. Joint principles: Integrating behavioral health careinto the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:183-5.

- Sunderji N, Waddell A, Gupta M, et al. An expert consensus on core competencies in integrated care for psychiatrists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;41:45-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waugh M, Calderone J, Brown Levey S, et al. Using Telepsychiatry to Enrich Existing Integrated Primary Care. Telemed J E Health 2019;25:762-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shore JH. Best Practices in Tele-Teaming: Managing Virtual Teams in the Delivery of Care in Telepsychiatry. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019;21:77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.), Donaldson MS, editors. Primary care: America’s health in a new era. Washington: National Academy Press, 1996:395.

- Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet] 2012 Oct 17 [cited 2019 Oct 9]; Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2

- Grace SM, Rich J, Chin W, et al. Implementing Interdisciplinary Teams Does Not Necessarily Improve Primary Care Practice Climate. Am J Med Qual 2016;31:5-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen N, Sockalingam S, Charow R, et al. Education programs for medical psychiatry collaborative care: A scoping review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018;55:51-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kern JS, Cerimele JM. Collaborative Care for Patients With a Bipolar Disorder: A Primary Care FQHC-CMHC Partnership. Psychiatr Serv 2019;70:353. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lowenstein M, Bamgbose O, Gleason N, et al. Psychiatric Consultation at Your Fingertips: Descriptive Analysis of Electronic Consultation From Primary Care to Psychiatry. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e279. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coulter C, Baker KK, Margolis RL. Specialized Consultation for Suspected Recent-onset Schizophrenia: Diagnostic Clarity and the Distorting Impact of Anxiety and Reported Auditory Hallucinations. J Psychiatr Pract 2019;25:76-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Daveney J, Panagioti M, Waheed W, et al. Unrecognized bipolar disorder in patients with depression managed in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2019;58:71-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hirschfeld RMA, Vornik LA. Recognition and diagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65 Suppl 15:5-9. [PubMed]

- Merten EC, Cwik JC, Margraf J, et al. Overdiagnosis of mental disorders in children and adolescents (in developed countries). Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2017;11:5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nasrallah HA. Consequences of misdiagnosis: inaccurate treatment and poor patient outcomes in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:e1328. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thombs B, Turner KA, Shrier I. Defining and Evaluating Overdiagnosis in Mental Health: A Meta-Research Review. Psychother Psychosom 2019;88:193-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults [Internet]. Third Edition. American Psychiatric Association, 2015.

- Rush AJ, Aaronson ST, Demyttenaere K. Difficult-to-treat depression: A clinical and research roadmap for when remission is elusive. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2019;53:109-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association, editors. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

- American Psychiatric Association. Telepsychiatry Toolkit [Internet]. American Psychiatric Association. [cited 2019 Oct 19]. Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit

- Leentjens AFG, Boenink AD, Sno HN, et al. The guideline “consultation psychiatry” of the Netherlands Psychiatric Association. J Psychosom Res 2009;66:531-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shore JH, Yellowlees P, Caudill R, et al. Best Practices in Videoconferencing-Based Telemental Health April 2018. Telemed J E Health 2018;24:827-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shore JH, Hilty DM, Yellowlees P. Emergency management guidelines for telepsychiatry. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007;29:199-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yellowlees P, Burke MM, Marks SL, et al. Emergency telepsychiatry. J Telemed Telecare 2008;14:277-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Calderone J, Lopez A, Schwenk S, Yager J, Shore JH. Telepsychiatry and integrated primary care: setting expectations and creating an effective process for success. mHealth 2020;6:29.