Developing a WhatsApp hotline for female entertainment workers in Cambodia: a qualitative study

Introduction

Female entertainment workers (FEWs) in Cambodia experience high levels of stress due to economic hardship, exposure to violence, and harassment by law enforcement because of their employment nature (1). These stressors can have a significant impact on their mental health and emotional well-being (2). FEWs describe young women employed at establishments such as karaoke bars, restaurants, beer gardens, or massage parlors who may also engage in transactional sex (3). There are approximately 40,000 FEWs in Cambodia (4). FEWs are considered an underserved and marginalized population and are disproportionately affected by experiences of gender-based violence (GBV) compared to the general population (4-6). In Cambodia, experiences of GBV and other stressors among FEWs are further intensified by social and structural factors, including entrenched poverty, gender inequality, discrimination, and stigmatization (7-9).

FEWs often come from poor and rural families and migrate to larger cities at a young age in hopes of earning higher wages to remit to their families (1). These young women commonly seek employment in the garment industry, which comprises 70% of Cambodia’s total exports (8). However, due to long work hours, low pay, and unhealthy working conditions, many women take higher-paying jobs offered by entertainment venues, where some may engage in selling sex to further increase their earnings (1). Despite the increased pay, FEWs in Cambodia are frequently victims of violence associated with their occupation, where 37.5% of FEWs report having experienced some types of violence the past six months, and more than half of FEWs report their clients as the main perpetrator (10).

As a marginalized population, FEWs face many barriers to accessing violence prevention and response services despite the disproportionate rates of experiencing violent encounters. For instance, FEWs often report facing discrimination from providers when seeking health and support services (9). Additionally, their health access has been further exacerbated by the introduction of Cambodia’s 2008 Law on the Suppression of Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation, which aimed to criminalized prostitution (10). In Cambodia, outlawing prostitution has ultimately amplified the stigma and discrimination associated with entertainment work and deterred FEWs from carrying condoms and reporting violence instances to the police (9,11,12).

Additionally, the 2008 law is associated with a substantial increase in FEWs as more women move from traditional sex work venues, such as brothels, to entertainment venues where they can continue to transact sex for supplemental income (11). However, despite treaties and protocols to protect women from violence, almost one in four women in Cambodia is a survivor of some form of GBV, including physical, emotional, or sexual violence (13). Additionally, a study on men and GBV in Cambodia found that 32.8% of men reported perpetrating physical or sexual violence, or both, against an intimate partner in their lifetime, and one in five men reported raping a woman or girl (13).

Emotional support hotlines are one strategy to address GBV (14). Hotlines with voice or text options are not a new method of providing support globally—the US-based Rape Abuse Incest National Network (RAINN) has been using an online hotline since 2007 (15). Online hotlines with voice and text options have been a way to reach people who are talking about what happened to them for the first time and may not have reached out in any other way. Chatting online is now a normal and preferred form of communication especially for younger users and may feel more private in that it can’t be overheard (15). The RAINN network found that the online communication offers survivors a way to control the pace and content of the conversation in a way that they could not on the phone. RAINN has found that the chat system can be especially useful for survivors who experience more violent trauma and may not ever be able to speak about their experience out loud. They have found that survivors ended up revealing more than they typically do using their phone hotline (15).

A recent review of studies documenting the use of WhatsApp in health found that WhatsApp is a promising system for communicating between health professionals and the general population such as for telemedicine. The review also calls for more rigorous evaluations of WhatsApp interventions in health (16). However, currently, no app-based hotlines exist in Cambodia and there are no hotlines tailored to FEWs in Cambodia. In 2016, an internet hotline for reporting child sexual exploitation and abuse was launched in Cambodia by an anti-pedophile international non-governmental organization (NGO). The organization reports that their online hotline has resulted in several arrests and investigations related to online abuse and child pornography (17). The nature of the calls to the hotline were mainly around reporting suspicion behaviors seen in real life or on social media related to child prostitution or trafficking.

Despite not having hotlines for GBV survivors, there are several high-quality services available for people experiencing sexual violence in the form of both medical and non-medical care including psychosocial support, rape kits, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), legal advice and legal aid. KHANA’s SMARTgirl program runs various “safe spaces” where survivors of GBV can show up to seek support and referrals. Referrals include connections to organizations that can directly facilitate and support GBV survivors in filing lawsuits against perpetrators, clinics that provide post-GBV clinical services to survivors such as conducting rape kits, and domestic violence shelter services (18). Unfortunately, these in-person services are underutilized; community workers feel this is because of fear, stigma, and shame of approaching providers.

KHANA, a public health NGO in Phnom Penh, is developing a WhatsApp-based hotline for FEWS that would offer both phone and text support to callers. For context, there were 21.18 million mobile connections in Cambodia in January 2021 which is equivalent to 125.8% of the total population. There were 12 million social media users in Cambodia which is 71.3% of the population. In addition, internet penetration in Cambodia was 52.6% (19). In Cambodia, WhatsApp was selected because it is a secure end-to-end encrypted messaging service, which means only the two parties involved can see and read what is sent, while third parties—including WhatsApp—can’t access the messages. In previous research, we found that among Cambodian FEWs, online chatting (often using Facebook Messenger) is their preferred form of communication (20). Unfortunately, Facebook Messenger is not a secure chat system and third parties can access the content of messages unless an encryption feature is enabled in the settings. In addition, WhatsApp is available using wi-fi which is widely available in Phnom Penh and therefore does not incur airtime costs for survivors.

The KHANA team recognizes that it is vital to incorporate feedback from FEWs regarding their GBV experiences and emotional support needs to appropriately adapt a hotline and promote service usage. This study aims to gather qualitative data on stressors, coping strategies, and preferences to inform the development of a WhatsApp hotline for FEWs in Cambodia.

We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-12).

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted in August 2020 using data from five focus group discussions (FGDs) with 8–10 participants each and 10 in-depth interviews (IDIs) when data collectors felt we approached data saturation. Peer leaders and outreach workers, trained local female staff, worked were recruited from existing staff at KHANA national NGO in Phnom Penh as data collectors. We used convenience sampling to identify participants. This method was cost-effective because outreach workers could recruit participants during their regular outreach activities and invite them to attend data collection events. Outreach workers invited any FEWs in their outreach areas to join the focus groups. Participants were recruited by peer data collectors or outreach workers using a recruitment script. Participants were offered $8USD for FGD and IDI participation to compensate them for time and travel. If they left the interview or focus group before completion, they received only $4USD. We included FEWs who were aged ≥18 and worked at entertainment venues in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. We included FEWs who could provide informed consent. We excluded minors, those working in entertainment but not at established venues, and those who could not provide informed consent.

Data collection procedures

Before data collection, verbal informed consent was sought from each study participant. Data collectors signed the consent form to confirm that the study participants had been briefed about the study, were assured of the nature of their confidentiality, the fact that they may already know or encounter members of the FGD in their regular life, and had given their informed consent to participate in the study. Study participants were informed of the option for escorted referrals to appropriate existing services in the province if they so wished at any time during participation or after. This research topic is highly stigmatizing and the average literacy level in this population was low. Therefore, verbal consent was the most appropriate form of consent so that no other identifying information was collected.

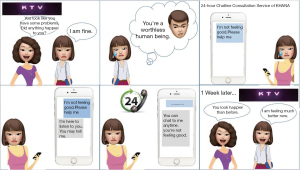

During the FGDs and IDIs, facilitators asked participants to fill out a simple 10 item demographic questionnaire. Then a trained female facilitator asked open-ended questions from the FGD and IDI guides. The guides were developed based upon our chatline protocol and guidance from, “Qualitative Data Collection Tools” (SAGE Publishing, 2020). The guide used the following section headers: Introductory Questions, Transition Questions, Depth Question, Material Assessment, Scenario-based Activity and Closing Questions. During the Material Assessment, participants were asked to review and respond to a comic strip showing the use of the chat option of the hotline (Figure 1). During the scenarios-based activity, participant listened to an audio recording of a hypothetical voice call between chatline staff and a caller (Appendix 1). We decided to use audio and visual aids in the data collection process as this is a population that has low literacy and may feel overwhelmed by any written prompts. FGDs lasted approximately 90 minutes, while IDIs lasted approximately 60 minutes. All data collection occurred at the SMART girl community centers run by community-based organizations. All FGDs and IDIs were digitally-recorded and transcribed in Khmer. Transcriptions were then translated in English. Bilingual staff members double-checked the translation.

Ethical considerations

During the informed consent procedure, we informed participants in the FGDs that there could have been an infringement on privacy if participants felt pressured or got caught up in the moment and disclosed personal information to people, they may know or see in their workplace or dormitories. All study procedures took place in a private space in a community center where only study personnel was admitted to address the privacy concerns. Participants were informed about the nature of FGDs and the lack of anonymity they present. Participants were also reminded about the voluntary nature of their participation and their rights to end their study participation at any point during the study without any consequences. There is also a risk of psychological distress as a result of answering questions about sensitive subjects such as witnessing or experiencing violence. To address these risks, all study participants were informed about the voluntary nature of their participation and their right to end their study participation at any point during the study without any consequences. They were made aware of free youth-friendly counseling services and were also given information about crisis centers and other relevant referrals, and they will be offered escorted referrals.

Facilitators were trained to identify if participants became overwhelmed with emotion to the point that they could not continue with the interview or focus group, or if they suggest that they may want to harm themselves or others. This did not occur during the study however facilitators were prepared to withdraw them from the study and immediately escort them to emotional and psychological support services.

The records of this study were kept confidential. The research team did not include the name or personal identifiers of any participants involved in the research in our reports. Electronic transcripts are stored on a password-protected laptop. The research coordinator and principal investigators are the only people who will have access to these records. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Cambodia National Ethics Committee for Health Research of Cambodia (169 NECHR) and Touro University California (PH-0220) and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Qualitative analysis

Given the study’s primary aim to ground the intervention in FEWs distinct needs and priorities, primary structural coding (21) was used to identify preferred characteristics and functions of the intervention. Notes taken during data collection and initial broad codes were constructed by Cambodia research staff. International researchers supported the next phase of analysis which included codebook development. As more secondary themes arose during codebook development (e.g., the stressors experienced by FEWs and their current coping strategies), an inductive thematic analytical approach was selected to categorize these data (22). However, as stressors and coping mechanisms used by FEWs have been well documented in other published studies (23), this study only provided a brief summary of those results.

The drafted codebook and associated analytic memos were produced by the authors. The authors then reviewed the drafted codebook via videoconference. Discrepancies were resolved and final themes were selected. The transcripts were then coded line-by-line using the final codebook. The results of the codebook, inclusive of both the structural and inductive themes, are provided below. In addition, theme of “Type of Support” which was identified as having the most influence on staff training for the hotline, was examined in great detail. The number of times a type of support was mentioned in the transcript the number of people who mentioned it was captured in a table presented in the results section.

Statistical analysis

As this research with qualitative in nature, we did not use any quantitative analysis tools.

Results

A total of 53 participants were included in this study. Based on the short demographic questionnaire, we found that participants had a mean age of 29.4 years old, completed an average of 5 years of school, reported an average of 3.5 dependents, have worked in entertainment for an average of 4.4 years, make an average of $211/month and all of whom have access to a phone, 80% own their own cellphone phone, half of which are internet-enabled smartphones. Of participants, 52.8% worked in karaoke bars, 22.6% in street-based entertainment/sex work, 15.1% at restaurants and 9.4% at massage parlors (Table 1).

Table 1

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 29.4 (S8.3) |

| Years of school, mean (SD) | 5.1 (3.3) |

| Number of dependents, mean (SD) | 3.5 (2.2) |

| Monthly income, mean (SD) | 211.3 (112.9) |

| Years in entertainment, mean (SD) | 4.4 (3.8) |

| Marital status, % [n] | |

| Single | 20.8 [11] |

| Married | 28.3 [15] |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 50.9 [27] |

| Entertainment venue type, % [n] | |

| Karaoke | 52.8 [28] |

| Massage | 9.4 [5] |

| Restaurant | 15.1 [8] |

| Street-based | 22.6 [12] |

From the interview and focus group transcripts, we found that respondents discussed the following themes: stressors they experienced, their coping strategies, hotline characteristics including staff characteristics, modes of communication, hours of availability, types of support, and calls for transformational change. These themes and subthemes are presented below.

Stressors experienced

Participants identified several stressors associated with FEWs, including concerns about physical and mental health, fear related to experiences with the police or threat of arrest, and exposure to violence. FEWs’ risk is compounded by their financial instability.

Participant 6: I’m scared when [clients] use a knife or gun to threaten me and tell me to do as they say. I have to do it.

Participant 2: Since we come to work to earn money, and we want their money, we must agree to go with them…and we don’t know what their motive is, we don’t know what they are going to do to us. (Focus Group 1)

Coping strategies

The coping strategies identified by study participants can be categorized into passive/avoidance and active strategies. Passive strategies included ignoring or avoiding the problem, such as physically removing themselves from the situation or trying not to think about it. Several participants also mentioned the use of alcohol, drinking either alone or with friends, as a way to escape or cope with their stressors.

“I invite my friends to have some alcohol drinks. It could help me sleep at night and forget everything in the morning.” (Focus Group 4)

Active coping strategies employed by study participants included drawing upon internal resources (e.g., their strength, patience, will power, and determination), staying home or isolating to cope.

“For me, and for some people, I hide my feeling when I have a problem. I don’t like talking much. People who hide their feeling always feel upset and cry alone.” (Focus Group 2)

Others relied on an external (largely informal) network for support. This network of support included family members, friends, co-workers, and managers/bosses.

“I always call to tell my older sister. After I talked to her, I feel calm. She told me, husband and wife often have conflict like that. So, then I can be calm and get together with my husband again.” (Interview 4)

“When we get sad or anxiety, no matter if it is a personal or family matter, when we get really bad feelings, I discuss with my friends on how should I deal with it. (Focus Group 2)

Some participants who experienced violence or needed immediate interventions identified organizational sources of support or intervention, including the police or NGOs. Friends were the most frequently cited source of support.

Hotline characteristics

This theme encapsulated codes related to participants’ preferences for how the intervention was structured. This included their input on the staff characteristics, the mode of communication, and the hours of availability for the intervention.

Staff characteristics

When prompted to provide feedback on the comic strip, participants identified a number of preferences related to the characteristics of the chatline staff. Overwhelmingly, participants in both FGDs and IDIs preferred a female staff. They explicitly indicated an interested in someone who would “use sweet words,” speak in a gentle voice, and who exhibited characteristics of being soft, kind, and comforting. They also stressed the importance of someone who was non-judgmental and who did not discriminate or look down upon them.

As one FGD participant explained:

“We want you to talk with us without minding that we are telling you about our problems.”

Another participant continued:

“…without discrimination. You don’t discriminate (against) us. You love and console us like mother and daughters.” (Participants 5 and 8, Focus Group 1)

Further, participants indicated a need to feel that the staff was trustworthy and would keep their conversation confidential. When one participant was asked to describe the potential benefit of the intervention she stated:

[It would] help us not to think a lot, not to feel upset. Like if we feel upset, we don’t know where to go. Everyone around us are people we don’t talk to, therefore we don’t feel confident. We want someone who can listen and not pass our story out. Encourage us, then we would feel warm with that person. (Participant 4, Focus Group 2)

Mode of communication

Participants were asked to indicate their preferred means of communication for this intervention, and to elaborate on factors shaping this decision. They focused primarily on phone calls, messaging (text and/or voice), and chatting through an app such as Facebook or WhatsApp. Factors shaping participants selections included Wi-Fi availability, literacy, and privacy.

Nearly all FGD and IDI participants indicated a preference for a phone call, indicating it was easier, more immediate, did not require a smart phone or internet availability. One IDI participant elaborated on her preference for a phone call:

“I want to call directly… it’s fast. When I want to talk, I don’t want to send message. I want to speak with someone. Because I want fast feedback from other people, so I would like to call.” (Interview 3)

However, participants expressed concern about service availability, the cost if the chatline number was outside of their cellular network, and privacy if they wished to call during work.

Texting was also frequently discussed as a possible mode of communication. Some participants felt it was faster than calling, more convenient and private if they were unable to speak aloud by phone, and more cost effective as many had Wi-Fi at their workplace. As many participants pointed out, however, fully communicating through text messaging may be more difficult than by phone, and texting requires literacy. Participants indicated that voice messaging would circumnavigate the issue of literacy, however, very few indicated voice messaging as their preferred mode of communication.

Finally, some participants indicated an interest in using the chat function of an app to communicate with the staff. Chatting had the same benefits and drawbacks of text messaging. However, some participants also felt it may be easier to remember how to reach the service if it were through an app. Additionally, some suggested that it may be more flexible as the FEW could use either the voice call or chat functionality of the app.

Hours of availability

Overwhelmingly, participants indicated a preference for the intervention to be available 24 hours a day. This allows them to reach out for immediate help if they are experiencing violence at work, or if they are seeking more general support or advice, to contact the service during their non-working hours. When prompted to provide a time range if the intervention were to only be available for 15 hours, most indicated a preference for availability during the late afternoon to early morning hours.

Types of support from hotline staff

When participants were asked to describe how the hotline could support them given the stressors they are experiencing, they indicated a range of support types (See Table 2). The authors categorized each supportive function into four overarching themes: to provide general emotional support, support mental health, protect physical health and safety, and give general guidance. The table describes how often a certain type of support was mentioned in the transcripts and how many individual people mentioned the type of support. For example for encouragement/emotional support, 15 different people mentioned this type of support 71 times.

Table 2

| Type of support | Number of times this type of support was mentioned | Number of people who mentioned this type of support |

|---|---|---|

| Provide general emotional support | ||

| Provide encouragement/emotional support | 71 | 15 |

| Console | 10 | 4 |

| Listen | 3 | 3 |

| Give general guidance | ||

| Give advice/solutions to problems | 65 | 14 |

| Consult about family problems | 6 | 4 |

| Provide career guidance | 3 | 2 |

| Support for mental health | ||

| Improve mood | 40 | 14 |

| Support with depression/suicidal thoughts | 14 | 9 |

| Suggest concrete actions to improve mood | 10 | 5 |

| Protect physical health and safety | ||

| Provide immediate help for violence | 25 | 7 |

| Suggest concrete actions to stay safe | 5 | 5 |

| Refer to services | 5 | 2 |

| Provide steps to protect health | 2 | 1 |

| Help them feel safe | 1 | 1 |

Overall, the primary function of the intervention that participants identified was for the respondent to provide emotional support and encouragement. This included listening to the FEW and consoling her. One participant contrasted this type of support with the type she has received in the past:

Some people really encourage us. But the way they encourage while we feel pressured or upset pushes us to be even more upset. I don’t want the pusher; I want those who can encourage me instead. When I feel down, I want someone to comfort me. The most important thing is that they can make me stronger, not weak. (Interview 3)

In addition to emotional support, some participants indicated a need for more direct guidance, including the provision of general advice or solutions. One FGD participant described this:

“They should give us advice…I want them to give us detailed answer, and tell us what we should do. When they do that, we will feel better and won’t have that problem again.” (Participant 1, Focus Group 3)

A few participants also sought advice related to their career. In one FGD, when asked about preferred functions of the intervention, a participant stated: “We want another job, we don’t want to do this anymore.” (Participant 9)

The moderator clarified “you want us to give advice?” and another participant elaborated: “Some of us can’t read or write, and some don’t have an identity card…most places don’t hire people who have no identity card or who can’t read and write. We need a place to hire those who only have to be good at their job. We really want to quit this job.” (Participant 6, Focus Group 2)

Support for mental health was also indicated as a need the intervention could address, particularly if a FEW is experiencing depression or thoughts of suicide. Participants also discussed more generally how engagement with the intervention could improve their mood and benefit their overall mental health. One participant described this:

Human beings usually encounter problems that may affect their mental status, and mental health is very important. We need one, or a few people to stand by us…we can tell them about our problem so they can tell us what to do. (Participant 1, Focus Group 3)

Finally, participants discussed the ways that the intervention could help them protect their physical health and safety. They sought advice for ways they could maintain their health (i.e., related to sexually transmitted infections) and referrals to health services. They also indicated a need for concrete actions to preserve their physical safety. In instances where FEWs were threatened with or experiencing violence, they also described the ways the intervention could provide them with immediate assistance. This could include calling the police, acting as a mediator between FEWs and clients, or providing her with in-person support. One IDI participant described how this could work if a woman were sexually assaulted:

First the staff] need to report to the police…second [they] call her to ask about what happened, her location…so they can come to her instantly. I want them to come instantly to see what happened exactly, to stop the victim from the continuous abuse and suffering because she doesn’t have anyone to help. So when there’s people to help her she would feel better…sometimes it could even cause the victim to commit suicide if there’s no one to help her, no one to solve the problem for her. If you can help her, I think you can encourage us a lot. (Interview 9)

Implementation of the hotline

Barriers to the intervention. Participants identified a number of barriers related to the implementation or use of the intervention. Most were previously categorized under ‘mode of communication’ and included aforementioned factors related to phone access and service availability. In addition to these, participants discussed some personal barriers related to the use of the intervention, including embarrassment, shyness, and a lack of courage. Some also identified fear as a barrier, particularly if they were calling because their personal safety would be at risk.

I’m afraid that if we have problems and call to you, if the one who abused us knows about it, if they think we are calling to report them to police officers, which could cause them troubles, they would come to murder us. So it’s difficult. (Interview 9)

Dissemination. Another barrier related to the use of the intervention was knowledge of its existence. To this end, some participants provided suggestions on how best to inform FEWs of its existence. Participants suggested advertising through social media, printing information on paper and giving directly to FEWs, advertising via TV or radio, and spreading awareness via word of mouth.

Calls for transformational change

While most participants felt that the intervention could bring them a sense of relief, safety, and could improve their mood, some felt that it alone could not alleviate the stressors they were exposed to, particularly related to violence. One participant described this:

“As we are living, we can’t run away from problems. (Rape) can happen every day. So your organization can’t solve our problems every day. We have a lot of problems to solve and one time solving won’t work for us. And I don’t want to bother you every day”. (Interview 5)

Others expanded upon this and expressed a need to focus on broader efforts to bring justice to victims or end violence. The dialogue in one interview highlights this:

Moderator: How do you think the victim would feel after talking to our staff?

Participant: To me, I feel better…not fully recover just feel better.

Moderator: So what do you think would make you feel totally okay?

Participant: I want you to take the criminal to prison.

(Interview 8)

Another participant concisely stated: “We want to find justice for them…I don’t want GBV to happen anymore.”

Discussion

Our findings suggest that FEWs in Cambodia would prefer a 24 h hotline with voice and text options that provides emotional support from kind and comforting female staff who can give general advice for personal problems, encouragement that will improve long term mood and address depression from stress and violence, and immediate help for violence. This has been found in other populations where both immediate crisis support is needed as well as support for the long-term effects of violence (24). Having a text and voice options may allow callers to have more privacy and disclose more personal information than a voice-only option (15). Using WhatsApp offers a secure way to offer these services.

Our qualitative methodology was successful in identify themes and informing intervention development. Broadly, other studies have demonstrated how intervention development is benefitted by initial qualitative inquiry for specific patient populations (25), in collaboration with hard-to-reach populations (26) and for healthcare services such as helplines (27). All these studies used the similar qualitative methodology of semi-structured interviews, while we also used FGDs and audiovisual aids.

Collecting respondents’ inputs on a support chatline to inform project development is also seen in the literature from a review that collected participants’ responses towards hotlines for youth (28) and a study that documented the development of a new helpline for emotional support during the COVD-19 pandemic in India (29). Research around chat-based hotline development and quality improvement can also be seen emerging in the literature using simulation exercise (30) and the role of content support systems (31).

While this study contributes to the emerging literature around app-based hotlines, it has limitations. Because we used non-probability sampling, selection bias may affect our findings. Participants who are generally more engaged and proactive joined our study, which may have led to the collection of information that may only be relevant for a subset of the population of FEWs. In addition, because we used FGD methodology, social desirability bias may have affected respondents’ comments. Respondents may have made comments that were more socially-desirable within their group and may not have expressed their true feelings. Therefore, our intervention may be influence by misleading comments. Adding IDIs to our methodology helped to triangulate themes and checking in with outreach workers and providers who serve this population to validate our findings.

Conclusions

This qualitative study offers textured evidence to inform chatline development and staff training that is tailored to the needs of this specific population. The methodology was successful in drawing out detailed feedback and preferences from FEWs. FEWs expressed a desire for emotional support through a WhatsApp hotline and also acknowledged the complicated structural factors that cause stress and fear in their lives include abuse and violence. Linking this intervention with crisis response, legal support and longer-term in-depth counseling as well as using information gathered from this project to inform a larger structural and policy level changes should be part a foundational part of this project.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the outreach workers, data collectors, facilitators and interns who helped to make this study possible. We would also like to thank the participants for sharing their voice and time.

Funding: This study was funded by the Sexual Violence Research Institute (SVRI).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-12

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-12

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-12

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-12). Dr. Carinne Brody serves as an unpaid editorial board member of mHealth from March 2021 to February 2023. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Cambodia National Ethics Committee for Health Research of Cambodia (169 NECHR) and Touro University California (PH-0220) and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Brody C, Chhoun P, Tuot S, et al. Childhood conditions, pathways to entertainment work and current practices of female entertainment workers in Cambodia: Baseline findings from the Mobile Link trial. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216578. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brody C, Chhoun P, Tuot S, et al. HIV risk and psychological distress among female entertainment workers in Cambodia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:133. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cambodia - addressing HIV vulnerabilities of indirect sex workers during the financial crisis: Situation analysis, strategies and entry points for HIV/AIDS workplace education. [cited 2021 Feb 11]. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/asia/publications/WCMS_165487/lang--en/index.htm

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Cambodia. Country Programme Brief. Phnom Penh: UNFPA Cambodia, 2014.

- Argento E, Reza-Paul S, Lorway R, et al. Confronting structural violence in sex work: lessons from a community-led HIV prevention project in Mysore, India. AIDS Care 2011;23:69-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:538-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuen WW, Tran L, Wong CK, et al. Psychological health and HIV transmission among female sex workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care 2016;28:816-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The World Bank. Cambodia Economic Update October 2018: Recent Economic Developments and Outlook. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/cambodia/publication/cambodia-economic-update-october-2018-recent-economic-developments-and-outlook

- Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport. Examining life experiences and HIV risks of Young entertainment workers in four Cambodian cities. Kingdom of Cambodia, Nation Religion King, 2012.

- Wieten CW, Chhoun P, Tuot S, et al. Gender-Based Violence and Factors Associated with Victimization among Female Entertainment Workers in Cambodia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Interpers Violence 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maher L, Dixon T, Phlong P, et al. Conflicting Rights: How the Prohibition of Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation Infringes the Right to Health of Female Sex Workers in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Health Hum Rights 2015;17:E102-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eisenbruch M. Violence Against Women in Cambodia: Towards a Culturally Responsive Theory of Change. Cult Med Psychiatry 2018;42:350-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fulu E, Jewkes R, Roselli T, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1:e187-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finn J, Garner MD, Wilson J. Volunteer and user evaluation of the National Sexual Assault Online Hotline. Eval Program Plann 2011;34:266-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grant R. Why Aren’t More Crisis Hotlines Offering Chat-Based Help? The Atlantic. July 13, 2015. Accessed on September 3, 2019. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/07/online-crisis-hotlines-chat-prevention/398312/

- Giordano V, Koch H, Godoy-Santos A, et al. WhatsApp Messenger as an Adjunctive Tool for Telemedicine: An Overview. Interact J Med Res 2017;6:e11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hawkins H. Internet Hotline Helps Combat Child Sexual Exploitation, Abuse. The Cambodia Daily. Accessed on September 3, 2019. Available online: https://www.cambodiadaily.com/news/internet-hotline-helps-combat-child-sexual-exploitation-abuse-125326/

- KHANA. Replicating Our Success toward Expanding Univeral Health Coveras: Leave No-One Behind. 2019 Annual Report. Available online: http://khana.org.kh/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/KHANA-Annual-Report-2019_ENG.pdf

- Digital 20221: Cambodia. February 11, 2021. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-cambodia

- Brody C, Tatomir B, Sovannary T, et al. Mobile phone use among female entertainment workers in Cambodia: an observation study. Mhealth 2017;3:3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saldaña J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd edition. Sage. 2016.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77-101. [Crossref]

- Brody C, Kaplan KC, Tuot S, et al. "We Cannot Avoid Drinking": Alcohol Use among Female Entertainment Workers in Cambodia. Subst Use Misuse 2020;55:602-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colvin ML, Pruett JA, Young SM, et al. An Exploratory Case Study of a Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline: Training and Practice Implications. Violence Against Women 2017;23:973-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Withall J, Haase AM, Walsh NE, et al. Physical activity engagement in early rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study to inform intervention development. Physiotherapy 2016;102:264-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang AW, Ash TR, Tovar A, et al. Exploring Parenting Contexts of Latinx 2-to-5-Year Old Children's Sleep: Qualitative Evidence Informing Intervention Development. J Pediatr Nurs 2020;54:93-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams M, Jordan A, Scott J, et al. Service users' experiences of contacting NHS patient medicines helpline services: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e036326. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mathieu SL, Uddin R, Brady M, et al. Systematic Review: The State of Research Into Youth Helplines. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2021;60:1190-233. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ransing R, Kar SK, Menon V. National helpline for mental health during COVID-19 pandemic in India: New opportunity and challenges ahead. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;54:102447. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koonin LM, Sliger K, Kerr J, et al. CDC's Flu on Call Simulation: Testing a National Helpline for Use During an Influenza Pandemic. Health Secur 2020;18:392-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salmi S, Mérelle S, Gilissen R, et al. Content-Based Recommender Support System for Counselors in a Suicide Prevention Chat Helpline: Design and Evaluation Study. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e21690. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Brody C, Reno R, Chhoun P, Ith S, Tep S, Tuot S, Yi S. Developing a WhatsApp hotline for female entertainment workers in Cambodia: a qualitative study. mHealth 2022;8:5.