Validation of a novel mobile phone application for type 2 diabetes screening following gestational diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects 8% of all pregnancies in the United States (1,2) and 4% to 14% of individuals diagnosed with GDM will screen positive for type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in the postpartum period (3). Recognizing this high burden of disease, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all individuals diagnosed with GDM undergo screening at 4–12 weeks postpartum using a 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (2hr OGTT) (4). Patient follow-up with postpartum screening been reported as low as 20% nationally (2). Telemedicine has enabled bidirectional contact and screening in affordable and immediate ways to address maternal health and postpartum services (5). Furthermore, fasting blood glucose (FBG) screening presents a potential opportunity to improve follow-up and alleviate barriers to postpartum diabetes care as screening can be completed at home using the devices and lancets utilized during pregnancy. FBG screening has shown to be an effective screening method because it is easier and faster to perform, more convenient and less expensive in non-pregnant individuals (6,7). The use of FBG screening among individuals diagnosed with GDM remains understudied. Thus, the objective of this study was to examine the use of FBG for screening T2DM compared to standard 2hr OGTT among individuals diagnosed with GDM. We sought to develop a mobile application and web-based forms for reporting FBG values in the postpartum period. We present the following article in accordance with the STARD reporting checklist (available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-36/rc).

Methods

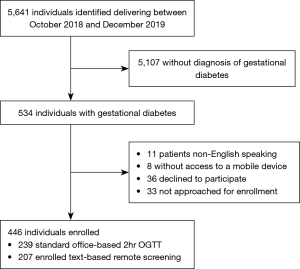

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Before the initiation of the study, an approval by the ChristianaCare Institutional Review Board (No. #39013) was obtained. This was a single-center, cluster prospective interventional study of individuals diagnosed with GDM between October 2018 and December 2019 at a tertiary care, teaching hospital in Newark, Delaware, United States. From October 2018 through April 2019, all patients diagnosed with gestational diabetes were enrolled in standard follow-up screening while all consecutive patients diagnosed with gestational diabetes were enrolled in our dual program from May 2019 through December 2019. Informed consent was taken from all individual participants. The diagnosis of GDM was made based on two-step screening using a cut-off of 135 mg/dL for 1-hour 50-g OGTT and Carpenter and Coustan cut-offs for 3-hour 100-g OGTT (4). At the time of admission to labor and delivery, patients were screened for eligibility; a trained research coordinator enrolled individuals prior to hospital discharge. Individuals were included if they were diagnosed with GDM and ≥18 years of age at the time of delivery. Patients without access to a mobile smartphone or whose primary language was not English were excluded from this study. Educational materials and instruction to keep glucose meter and lancets for future testing were provided. Participants were given instructions on downloading the mobile application or using a web-based version. At 6 weeks postpartum, participants enrolled in remote screening received automated, electronic forms requesting FBG on three consecutive days. Reminder texts with links to the web-based platform were sent each week until 12 weeks postpartum, at which point patients were considered lost to follow-up (Figure 1). All participants were encouraged to undergo T2DM screening with 2hr OGTT during the study period, regardless of FBG values. Follow-up was defined as having completed of 2hr OGTT screening or submitting all three FBG values within 12 weeks postpartum.

To assess the effectiveness of FBG screening, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predicted values (PPV), and negative predictive values (NPV) with exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CIs) compared to standard, 2hr OGTT were calculated. We hypothesized that individuals with all three FBG less than 100 mg/dL will screen negative on 2hr OGTT while participants with at least one FBG value greater than or equal to 100 mg/dL are at risk for screening positive on 2hr OGTT (3). Secondary outcomes, including both maternal and neonatal outcomes, were identified by the medication administration record, International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes, and chart review.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was completed using Stata statistical software (version 13.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were compared with t-test and categorical variables with χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed using maternal covariates that met a P value threshold of 0.05.

Results

There were 5,641 individuals who delivered during the study period of October 2018 and December 2019, 534 of which were diagnosed with GDM (Figure 2). A total of 19 patients with GDM were not eligible for recruitment and 36 declined to participate. Of the 446 women meeting all inclusion criteria, 239 were enrolled in standard office-based 2hr OGTT screening and 207 were enrolled in dual 2hr OGTT and FBG screening via remote texting.

Maternal demographics are presented in Table 1. We found no demographic differences between the groups with respect to age, rate of nulliparity, race, ethnicity, insurance type and time from delivery to screening test.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Standard office-based 2hr OGTT (N=239) | Text-based remote screening (N=207) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (years) | 32.3±5.2 | 32.9±5.4 | 0.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.5 | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 136 (56.9) | 119 (57.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 46 (19.2) | 29 (14.0) | |

| Asian | 40 (16.7) | 43 (20.8) | |

| Hispanic | 17 (7.1) | 16 (7.7) | |

| Insurance | 0.05 | ||

| Public, state insurance | 96 (40.2) | 64 (30.9) | |

| Criteria used for GDM diagnosis | 0.02 | ||

| Elevated 1hr OGTT (>200 mg/dL) | 89 (37.2) | 55 (26.6) | |

| Elevated 3hr OGTT* | 150 (62.8) | 152 (73.4) | |

| GDM management | 0.06 | ||

| Diet only | 156 (65.3) | 130 (62.8) | |

| Oral hypoglycemic medication | 38 (15.9) | 41 (19.8) | |

| Insulin only | 19 (7.9) | 6 (2.9) | |

| Combination oral hypoglycemic medication and insulin | 26 (10.9) | 30 (14.5) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.2±1.7 | 38.4±1.5 | 0.4 |

| Nulliparity | 102 (42.7) | 94 (45.4) | 0.7 |

| Mean time from delivery to screening test (days) | 59.2 | 49.6 | 0.1 |

Data are expressed as number (%) and mean ± standard deviation. *, a diagnosis was made if two or more elevated thresholds were detected in fasting, 1-, 2-, and 3-hour plasma or serum glucose level of 95, 180, 155, 140 mg/dL, respectively. hr, hour; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance testing; GDM, gestational mellitus diabetes.

Validation of FBG

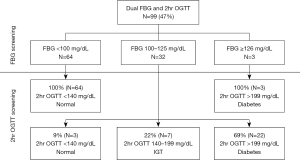

Ninety-nine individuals submitted all three FBG values and completed in-person 2hr OGTT screening. Figure 3 depicts the study protocol used to categorize FBG results. Cut-offs were determined prior to participant recruitment. Of the 64 patients who reported all three FBG less than 100 mg/dL, all 64 participants had normal 2hr OGTT results. Thirty-two individuals had FBG values ranging between 100 and 125 mg/dL. Three patients from this group screened negative for diabetes using standard 2hr OGTT cut-off of less than 140 mg/dL per ACOG guidelines (4). Seven individuals (7/32, 22%) had impaired fasting glucose on 2hr OGTT. The majority (69%) of patients with at least one FBG between 100 and 125 mg/dL screened positive for diabetes using the standard 2hr OGTT cutoff designated by ACOG. All participants with at least one FBG greater than or equal to 126 mg/dL screened positive for diabetes on 2hr OGTT.

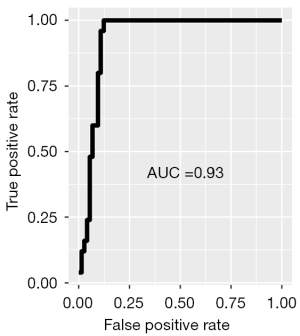

The NPV of FBG screening was 100% (95% CI: 94–100%) with a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI: 86–100%). The specificity of screening with FBG was 86% (95% CI: 77–93%) with a PPV of 71% (95% CI: 54–85%). Table 2 presents the test characteristics of using FBG screening compared to the gold standard 2hr OGTT. Test characteristics were plotted on a receiver-operating curve as shown in Figure 4. The area under the curve (AUC) illustrates the diagnostic ability of FBG as its discrimination threshold is varied. This particular receiver operating characteristic curve demonstrates that FBG is an acceptable screening method for T2DM, with an AUC of 0.93.

Table 2

| Test characteristics | % [95% confidence interval] |

|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100 [86, 100] |

| Specificity | 86 [77, 93] |

| Positive predictive value | 71 [54, 85] |

| Negative predictive value | 100 [94, 100] |

Follow-up

Postpartum follow-up occurred in 159 cases (36%). The rate of follow-up was higher among individuals enrolled in telehealth remote screening compared to those enrolled in standard office-based 2hr OGTT testing (99/207; 48% vs. 60/239; 25%, respectively; P<0.001). Individuals enrolled in mobile-based screening had higher detection rates of T2DM on 2hr OGTT compared to those enrolled in standard office-based 2hr OGTT alone (25/207; 12% vs. 13/239; 5%, respectively; P<0.02).

Individuals who were identified as non-black had higher rates of follow-up using office-based 2hr OGTT compared to patients who were identified as black (55/239; 23.0% vs. 5/239; 2.1%, respectively; P<0.02). This disparity was not observed in remote FBG screening as there was no statistical difference in follow-up among patients who identified as non-black compared to those who identified as black (89/207; 43.0% vs. 10/207; 4.8%, respectively; P=0.12). Table 3 shows rates of follow-up by treatment group.

Table 3

| Follow-up1 | Standard office-based 2hr oral glucose tolerance test (N=239) | Text-based fasting blood glucose screening (N=207) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 60 (25.1) | 99 (47.8) | <0.001 |

| Non-Black2 | 55 (23.0) | 89 (43.0) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5 (2.1) | 10 (4.9) | <0.001 |

Data are expressed as number (%). 1, follow-up was defined as having completed of 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test screening or submitting all three FBG values; 2, race/ethnicity was based on self-identification. FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Discussion

This is the first study to validate a step-wise screening protocol using FBG with confirmatory 2hr OGTT screening via remote text-based platforms among individuals diagnosed with GDM (3,8,9). We found that none of the participants with all three FBG less than 100 mg/dL screened positive for diabetes on standard 2hr OGTT. Ultimately, having all three FBG less than 100 mg/dL was consistent with 2hr OGTT and thus a robust screening test to exclude diabetes.

Previous reports have shown that using reminder texts is associated with higher rates of follow up compared to in-person standard 2hr OGTT alone (28% vs. 14%, respectively; P=0.01) (10). Our results are consistent with previous reports that suggest remote FBG screening is a feasible alternative to office-based 2hr OGTT.

We find our study generalizable to a tertiary care, teaching hospital, as we included all individuals diagnosed with GDM. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has evaluated postpartum follow-up rates using fasting capillary blood glucose through text-based, remote screening for T2DM. We accept the possibility of selection bias given the overall low attrition rates and our sample size of 446 individuals is small. The low follow-up rate in this study underscores the importance of investigating new strategies to improve continuity of care with postpartum T2DM screening. Furthermore, additional research is needed to assess the clinical utility of one or two FBG values. The present study utilized a pre-defined FBG cutoff 100 mg/dL. A larger analysis of remote FBG screening utilizing various cutoffs is needed to establish an optimal cutoff value.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that postpartum screening of individuals with GDM using FBG through text-based care has strong agreement with the recommended 2hr OGTT. Remote, FBG screening showed significantly higher rates of follow-up compared to standard office-based screening at our institution. In populations with low follow-up rates, text-based screening with FBG is a feasible alternative to screen for postpartum diabetes. Additional research is required to determine whether this intervention can be implemented for routine postpartum testing.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented as an oral presentation at the 40th annual pregnancy meeting of the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Grapevine, Texas; February 3-8, 2020. The authors would like to thank Lisa Pesce RN, Heather Ward, MSN, WHNP-BC, APN-C, Marjorie Pollack, NP, and Denise Bloemer, BA.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STARD reporting checklist. Available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-36/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-36/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-36/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://mhealth.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/mhealth-21-36/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the ChristianaCare Institutional Review Board (No. #39013), and informed consent was taken from all individual participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Casagrande SS, Linder B, Cowie CC. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and subsequent Type 2 diabetes among U.S. women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;141:200-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou T, Sun D, Li X, et al. Prevalence and Trends in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus among Women in the United States, 2006–2016. Diabetes 2018;67:121. -OR. [Crossref]

- Kitzmiller JL, Dang-Kilduff L, Taslimi MM. Gestational diabetes after delivery. Short-term management and long-term risks. Diabetes Care 2007;30:S225-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e49-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dobson R, Whittaker R, Jiang Y, et al. Effectiveness of text message based, diabetes self management support programme (SMS4BG): two arm, parallel randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2018;361:k1959. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dietz PM, Vesco KK, Callaghan WM, et al. Postpartum screening for diabetes after a gestational diabetes mellitus-affected pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:868-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- NICE. Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postpartum period (NG3). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2020.

- Hunt KJ, Conway DL. Who returns for postpartum glucose screening following gestational diabetes mellitus? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:404.e1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrara A, Peng T, Kim C. Trends in postpartum diabetes screening and subsequent diabetes and impaired fasting glucose among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus: A report from the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:269-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shea AK, Shah BR, Clark HD, et al. The effectiveness of implementing a reminder system into routine clinical practice: does it increase postpartum screening in women with gestational diabetes? Chronic Dis Can 2011;31:58-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Gomez Slagle HB, Hoffman MK, Caplan R, Shlossman P, Sciscione AC. Validation of a novel mobile phone application for type 2 diabetes screening following gestational diabetes mellitus. mHealth 2022;8:12.