VA mobile apps for PTSD and related problems: public health resources for veterans and those who care for them

IntroductionOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

Public health agencies are charged with maximizing the health and well-being of entire populations of people (1,2), often with scant resources allocated specifically to mental health (3,4). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is responsible for addressing the physical and mental health needs of veterans of the U.S. military, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is both highly prevalent among veterans (5) and strongly associated with healthcare utilization and costs (6,7). Addressing complex public health problems, like PTSD, requires weighing the best possible evidence and standards of care (8) with the challenges of providing mental health care across populations (9), including declining funding rates as a proportion of overall health care (10,11), stigma (12), lack of providers (13), and other major barriers to delivering mental health care (14,15). For veterans receiving VA healthcare, VA offers screening, treatment, and follow-up care for those with PTSD and has developed training and implementation services to support the use of evidence-based treatments. Even with these efforts, VA faces ongoing challenges in delivering measurement-based care (16), reducing treatment dropout (17), and continuing to improve treatment outcomes (18,19).

For PTSD in particular, evidence-based approaches to treating PTSD are not available for the vast majority of individuals who experience it (20,21). Resources are also particularly scarce for the large numbers of those who experience moderate or high levels of PTSD symptoms but do not meet full diagnostic criteria (22). Both public and private mental health care delivery systems face challenges in keeping up with demand (15), and recent changes to both the Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. §18001 [2010], and the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act, Public Law 113–146 [2014], are likely to place even greater pressures on under resourced community and private mental health providers and county and state public health agencies to address PTSD-related problems.

To address potential gaps in PTSD-related care, there have been many efforts to use technology to reach veterans, and others with PTSD who are not able or willing to use evidence-based approaches to PTSD treatment. VA is a world-leader in the diagnosis and treatment of PTSD, treating 619,493 veterans with PTSD in 2016 alone (23) since 2011, the VA’s National Center for PTSD, in collaboration with VA’s Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention (OMHSP) and the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Health Agency, has been involved in the development and evaluation of 15 mobile apps designed to provide support for evidence-based treatments and self-management strategies for individuals living with PTSD symptoms or related problems. Mobile applications are well-suited for addressing many of the challenges in meeting unmet mental health needs, though they are likely to be most effective when used as part of a broader mental health strategy. The ubiquity of mobile devices is a key benefit in extending reach: smartphones are used by 77% of the U.S. population (24) and 82% of active duty service members (25). Moreover, smartphones are nearly always both on and on your person (26). Furthermore, the apps are both tolerable and desirable: veterans have high levels of interest in using mobile apps for mental health-related concerns (27). Mobile technologies have been deployed successfully to reduce mental health problems, such as suicidal ideation (28), depression (29), sleep (30), and PTSD (31) to name a few. Moreover, mobile apps can be used to address PTSD-related needs at many different points of contact with the healthcare system: for use in screening for mental health conditions or tracking changes over time (32), as a means of providing immediate assistance while a patient is waiting for a higher level of care, for use in supporting the delivery of evidence-based treatment (33), for providing between-session homework exercises (34,35), to provide post-treatment support, and as a way to reach those who might not otherwise access mental health services. It follows that various large public health agencies have made policy to systematically increase the use of mobile apps to address public health problems. For example, VA’s 2018–2024 strategic objectives are to modernize VA service delivery, including the delivery of information and services through mobile apps and other technologies (36).

This paper will describe the history, rationale, evidence, and application of a public mHealth portfolio for addressing the needs and concerns of veterans and others experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress and PTSD.

History of VA mobile mental healthOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

In 2009, a team of psychologists who had been working on congressionally mandated web products for service members and veterans at the National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD) Dissemination and Training Division proposed building a mobile app to provide psychoeducation and self-management tools for PTSD in response to veteran feedback. By the fall of 2010, early builds of the app (PTSD Coach) were shared with VA leadership, who were impressed with its elegant, simple design, and solid execution of features (e.g., self-assessment and coping tools) and considered it an exceptional demonstration of innovative technology in government. In April 2011, PTSD Coach was released to the App Store becoming VA’s first publicly available mobile app. Almost immediately, PTSD Coach showed robust download numbers and began receiving acclaim from users, the press, professional organizations, and won national recognition (e.g., promotion by the official White House Blog, the FCC’s Chairman’s Award for Accessibility). Concurrently, VA leadership invited the NCPTSD team to submit a proposal to develop a mobile apps program for PTSD (and related conditions) and to serve as a resource hub for other VA entities considering mobile app development and research. The proposal included a comprehensive, coherent strategy to develop, maintain, evaluate, distribute, and support a suite of mobile apps that aligned with VA’s mission to disseminate, implement, and improve delivery of sound mental health information and evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for mental health conditions. In October, 2011 the mobile apps program began, which included a full-time mobile apps lead, an evaluator/researcher, and a program coordinator. It also included resources to support the design and development of three new apps each year and the maintenance of existing apps. Since then, the program has expanded to include additional part- and full-time team members. With the success of this program, in 2014, VA leadership established a national mobile health program within Mental Health Services that would work in close partnership with the NCPTSD team, in order to broaden the benefit mobile options could confer across many other presenting mental health problems and populations.

Need for public mobile mental health resourcesOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

Most large public health agencies have utilized mobile apps to address population-health challenges. For example, the English National Health Service (NHS) offers over 40 consumer-facing mobile apps and web applications (37), including 11 apps specific to mental health (e.g., Cove, Chill Panda, Stress and Anxiety Companion). The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) offers 11 consumer-facing and 9 provider-facing apps addressing everything from dental health to dietary recommendations to vaccine schedules. However, across all of these other public health agencies, there are currently no mobile apps specific to PTSD, only a handful that are specific to anxiety, depression, or stress management, and none that are specific to the needs of trauma survivors or integrate with existing systems of care.

In general, private-sector mobile mental health apps offer promise (38) but very few have been developed specifically for trauma survivors or veterans. Moreover, there are several major problems with the use of private-sector apps to address mental health concerns at the public health level, including: cost, privacy, stability, and responsiveness to stakeholders’ needs. With respect to cost, some of the best-studied mobile mental health applications are prohibitively expensive and could not be accessed by many of those who most need services (38). For example, Sleepio has shown substantial promise for reducing insomnia severity but costs several hundred dollars (39). Other evidence-informed apps, like Pacifica, Calm, Breathe, and Headspace, offer some free content, but require users’ personal information and limit most content to those who are able to pay a monthly fee. With respect to privacy, many private mental health apps collect, and reserve the right to share, personally-identifying and health information. Additionally, privacy policies for many mobile health apps can be difficult to find and even more difficult to understand (40). With respect to stability, the availability and long-term reliability of many private-sector mental health applications tends to be limited over time. There is high turn-over of technologies (e.g., yearly updates to mobile operating systems), many unique combinations of mobile app platforms and devices, high testing demands, and other challenges that require extensive and ongoing maintenance resources (41). Finally, with respect to responsiveness, private sector technologies are answerable to shareholders and investors and may be more heavily optimized for monetization than for addressing users’ mental health needs (42). The extent to which private mobile mental health apps are responsive to scientific investigation or user input is unclear, and many commercial mobile apps for mental health do not employ evidence-based behavior-change strategies (43).

Public health approaches to mobile mental health have the potential to address each of these limitations. First, because public health agencies are not constrained by profit motive, their apps can be offered at no cost to users and can therefore reach much broader audiences. Second, public health agencies like VA address privacy with the full protections of federal privacy laws, regulations, and policies. Because mental health-related concerns are inherently private and often highly stigmatizing, there is a need for resources that do not collect personally-identifiable information or pose privacy risks to users (44). VA mobile mental health apps do not ask for or store personally-identifying information of any kind. As described in more detail below, VA mobile mental health apps have been maintained over time, have a research base, and are responsive to stakeholder input.

VA mobile mental health portfolioOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

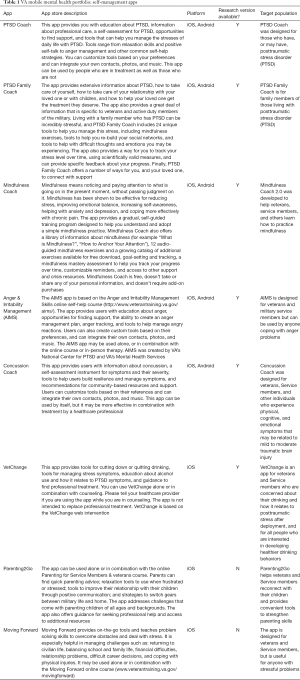

The VA’s mobile mental health portfolio consists of self-management apps and treatment-companion apps.

Self-management apps are designed to be used by anyone living with PTSD or trying to better understand PTSD, regardless of whether they are currently connected to care. There are currently eight self-management apps: PTSD Coach for PTSD-related self-care, PTSD Family Coach for loved ones of those with PTSD, Mindfulness Coach for learning and practicing skills in mindfulness, Anger and Irritability Management Skills (AIMS) for tracking and managing anger, VetChange for tracking and managing alcohol use, Parenting2Go for readjusting to parenting after being deployed, Moving Forward for problem-solving, & Concussion Coach for self-care related to mild traumatic brain injuries (see Table 1). These applications provide extensive educational content, interactive tools for skills-training and stress management, assessment and self-tracking features, and resources for connecting with support and finding professional care.

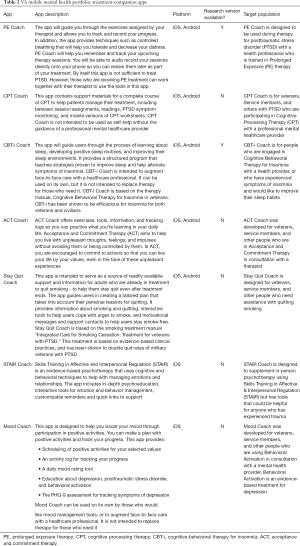

Full table

Treatment-companion apps are patient-facing and are designed to be used in conjunction with traditional therapist-guided evidence-based treatments (EBTs). There are currently seven treatment-companion apps to support the delivery of Prolonged Exposure therapy (PE Coach) for PTSD, Cognitive-Processing Therapy (CPT Coach) for PTSD, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-i Coach), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT Coach) for anxiety and depression, Integrated Care for Smoking Cessation (Stay Quit Coach), Skills Training in Affect and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR Coach) for PTSD, and Behavioral Activation for depression (Mood Coach; see Table 2). These apps make it easy for providers to demonstrate and encourage practice of key skills specific to each EBT, such as identifying and completing in vivo and imaginal exposure exercises, completing sleep diaries or thought records, and practicing relaxation exercises. Additionally, the apps contain handouts, worksheets, and explanations that are routinely used in the delivery treatment. Providers are able to demonstrate and use the apps in session, and the patient can use them between sessions and even after discharge to extend the benefits of treatment.

Full table

Evidence for VA mobile mental health resourcesOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

Evidence for the potential benefits of VA mobile mental health apps is accumulating across several important research fronts (see Table 3). These include studies showing support for their value as helpful psychoeducational self-help tools, powerful adjuncts to clinical care, and advantageous tools that are being widely used and appreciated by providers.

Full table

Regarding evidence for self-management of PTSD symptoms, PTSD Coach has been the subject of several studies. The first among these was an acceptability study with veterans in VA residential PTSD treatment (45). After using PTSD Coach for three days, participants (N=45) reported high satisfaction with the app and believed it was moderately to very helpful for managing their PTSD symptoms. In a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) among community trauma survivors with significant PTSD symptoms (N=49), those assigned to use PTSD Coach for one month showed significant improvement in their PTSD symptoms, whereas those assigned to a waitlist control condition did not (46). However, there was no significant difference in symptom change between conditions. In a follow-up, full-scale RCT with a larger community sample (N=120) and 3-month intervention period, significant treatment effects were found favoring PTSD Coach relative to a waitlist control condition on improvements in PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, and psychosocial functioning (31). A variant of PTSD Coach called Cancer Distress Coach, which was specifically designed for cancer survivors, has also shown promise. In a pre-post trial with 31 cancer survivors experiencing significant PTSD symptoms, nearly half (48.4%) reported a reliable improvement in their symptoms and almost a third (32.3%) evidenced clinically meaningful improvements (47). A study conducted by independent investigators (i.e., those not involved in the development of PTSD Coach) using a pre-post design with college students with significant PTSD symptoms (N=53) demonstrated that app use was associated with PTSD symptom improvement (48). Finally, to assess the reach, impact, use, and perceptions of the publicly available PTSD Coach, Owen and colleagues (49) examined aggregate usage data from over 150K downloads of PTSD Coach and 156 App Store and Google Play user reviews. They found that PTSD Coach was reaching those with elevated PTSD symptoms, use of symptom management tools was associated with reduced distress ratings, and that users appreciated the availability of the app and being able to use it during moments of need.

VA apps have also shown promise as well in the context of clinical care, particularly when used by patients in evidence-based psychotherapies for PTSD and common comorbidities (i.e., insomnia and smoking). This includes findings from a case-series with two patients enrolled in PE therapy who were assigned in a counterbalanced fashion to use or not use PE Coach for four of their eight sessions (50). Both patients reported greater satisfaction with care while using PE Coach, compared to when they did not use the app. It also includes a small-scale RCT of four veterans with insomnia and cannabis use disorder randomly assigned to use CBT-i Coach or a mood-tracking app (placebo control) for two weeks (51). Both participants assigned to CBT-i Coach reported improved sleep efficiency and reduced cannabis use while one participant in the control condition dropped out and the other had improved sleep efficiency but increased cannabis use. CBT-i Coach was also examined in a pilot RCT where CBT-i patients (N=18) were randomly assigned to use or not use the app during care (52). Findings supported the app’s feasibility (i.e., participants routinely used the app) and acceptability (i.e., app features were perceived as helpful), and a large treatment effect (although not statistically significant) was found for improved provider-rated patient adherence to the protocol.

Similar research has been conducted with Stay Quit Coach, the companion app for the Integrated Care for Smoking Cessation for PTSD protocol (53). A pilot RCT (N=11) with smokers with PTSD found that Stay Quit Coach was feasible and acceptable when used after a quit attempt (54). Likewise, findings of an open trial evaluating Stay Quit Coach among veteran smokers with PTSD (N=20) demonstrated that the app was feasible and acceptable, and treatment attendance and rate of bio-verified smoking abstinence appeared to be improved over what was found in the original trial [i.e., (53,55)]. Finally, in a novel application of integrating an app in care, Possemato and colleagues developed an intervention for VA primary care patients with PTSD coupling PTSD Coach with four brief sessions (i.e., 20–30 minutes) of clinician support (56) intended to address PTSD symptoms and increase the likelihood of accepting a referral to PTSD specialty care. A pilot RCT comparing this intervention to PTSD Coach use without support among VA primary care patients with PTSD (N=20) found that both conditions showed significant reductions in PTSD severity over eight weeks, with seven in the clinician-supported versus three in the self-managed groups reporting clinically significant improvements. Clinician-supported PTSD Coach also resulted in significantly more specialty PTSD care use over the 16-week follow-up period (57).

Another area of study has examined the clinical adoption, use, and perceived benefits of companion apps for EBTs from VA providers’ perspectives. Before releasing PE Coach, PE providers’ (N=163) perceptions of and intention to use the app were assessed following review of a brief, objective description of its core features and functions (58). Providers had favorable perceptions of the app’s relative advantage over existing PE practices, compatibility with their practice, and ease of use, with 75% agreeing that they would use it when it became available. One year after the app release, VA PE providers (N=217) were surveyed again to assess their perceptions and use of PE Coach (59). Perceptions of the app were equally favorable and half of the sample reported having used it with their PE patients, with 94% reporting intention to continue using it. Similar research has been conducted among VA CBT-i providers yielding comparable findings for CBT-i Coach (48,49). Finally, a qualitative study of 25 VA PE providers (who reported using PE Coach with 450 of their patients) found that providers appreciated that the app enhanced treatment credibility, “side-by-side” collaboration, and having forms and resources consolidated in the app, but did not appreciate lack of parity between Android and iOS versions of the app and not being able to readily access data stored in the app (60).

Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for themOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

Human-centered design (HCD) methodologies offer a promising way to ensure that evidence-based public health interventions, like mobile apps, can be effectively implemented in real-world settings (61,62). Although there are many distinct methodologies that are used in HCD, they all attempt to better understand, incorporate, and prioritize the end users’ needs, experiences, and desires (63,64). VA has incorporated HCD into its mobile products, by evaluating veterans’ needs and preferences and integrating them into apps (45,49,65). Additionally, VA has undertaken a program of user experience testing and has actively sought out and incorporated input from key stakeholders, including policy makers, frontline providers, veterans, and their family members. To date, VA has conducted interviews and user experience tests with hundreds of providers and veterans, across a variety of mobile applications, to better understand how apps are integrated into care, how they can be made to more easily support clinical interventions, and how they can better address unmet mental health needs. User input has been critical to identifying new psychoeducational materials, interactive tools, resources for providing additional support, graphic design improvements, and ways to make it easier for users to navigate the apps. By emphasizing input from veterans and those that provide care for veterans, it has made it possible to ensure that these apps are optimized for the purpose of facilitating recovery from PTSD. When it has not been possible, because of financial, personnel, or other constraints, to address needs identified by veterans and providers, such needs are documented and catalogued so that they might be included in future updates for existing apps.

Training providers in the use of mobile mental healthOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

A number of implementation science-based strategies have been proposed for rapidly disseminating evidence-informed interventions, including learning collaboratives, task-sharing, and therapist-level implementation strategies (66). Public health care-focused organizations such as VA and DoD pose both opportunities and challenges for implementation of new practices such as integrating mobile apps into clinical care. The value of apps as clinician-extenders is obvious in public-sector settings that are often under-staffed. However, large organizations can also stifle adoption of new practices and technologies through risk-averse regulations, stringent compatibility requirements, and bureaucratic cultures. The Practice-Based Implementation (PBI) Network was established jointly in VA and the DoD to serve as a field laboratory for implementing these types of innovative and emerging implementation science practices (67). The PBI Network offers providers with training and implementation support for practice changes and collects lessons learned to inform research and larger-scale implementation efforts.

With the emergence of mobile apps in the last decade, clinical integration of mobile mental health applications represents a relatively new frontier for many mental health providers. Providers have reported favorable attitudes towards mobile mental health (25,68), but adoption can be impeded by a variety of barriers including lack of familiarity with available technologies and limited training in how to successfully integrated tools into care (69,70). To address this unmet training need for military providers, DoD began offering workshops to support providers’ implementation of mobile health interventions in clinical practice beginning in 2014. To date, DoD has trained over 700 providers and has identified five core training competencies: evidence base, clinical integration, security and privacy, ethics, and cultural competence (71). In a 2017 pilot, VA providers were trained using DoD’s training model. One of the lessons learned from the PBI Network is that training alone is often not sufficient for sustained practice change. Therefore, in addition to training, providers were also offered twelve weeks of mHealth implementation support via a virtual community of practice (i.e., weekly call with other providers, facilitation, access to experts, and resource support). Providers were also given one-on-one support for creating therapist-level implementation plans and task-sharing for patient education materials and brief interventions. Since the end of the pilot, and in response to participants’ feedback and demand from the field, the PBI Network has created an ongoing monthly “Tech Into Care” community of practice conference call open to any VA provider interested in integrating mHealth into care. Virtual trainings and consultation are also now being requested and offered throughout VA. PBI-based implementation strategies for mobile mental health are co-occurring with an increase in rate of downloads of VA mobile mental health apps, suggesting the success of these types of strategies. As of February 2018, VA mobile mental health apps have been downloaded over 1.1 million times (72).

In addition to training providers on how to integrate mobile apps into the delivery of mental health care, efforts to widely disseminate the mobile app portfolio are both necessary and ongoing. Searching for an app to treat a specific mental health issue can be overwhelming, given the hundreds of options that appear when using search terms such as, “depression” or “anxiety” (73). The VA has worked to establish the “Coach” brand (e.g., “PTSD Coach”) to make searching for and recognizing these apps easier. However, how users first learn about these apps may impact whether or not they decide to use them (74). In consideration of the various ways in which people might be introduced to them, the National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD) has begun to flesh out a suite of dissemination materials for each app, including a basic marketing flyer and rack card, a more clinically-styled tri-fold brochure, a user guide for more detailed information (especially helpful for telehealth providers and patients), social media posts highlighting features within the app, and a video demonstrating use of the app. Materials are designed to be engaging but brief, and to convey practical information. While these materials are intended to be shared electronically, outreach efforts and physical presence at VA and in the community have also increased. Implementation and outreach initiatives to support the use of VA mobile technologies also highlight the fact that stakeholder feedback is welcomed, including concerns and suggestions for improvement from veterans, providers, and other users. Contact information for VA mobile mental health staff has been widely shared with VA provider communities of practice (e.g., CBT-i, PE, ACT).

Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental healthOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

VA mobile mental health apps are designed to facilitate both scientific investigation and use in clinical settings. Research (i.e., “instrumented”) versions of apps (see Tables 1,2) capture user data to support use in qualifying research studies, and include many of the apps in the portfolio, such as PTSD Coach, PTSD Family Coach, Mindfulness Coach, CBT-i Coach, and VetChange. These research apps collect fully de-identified, user-generated data, such as which areas of the app were visited, assessment data, and timestamps associated with key app-related activities, and these user-generated data can then be linked with other data sources, such as surveys or interviews. While VA policy and information technology requirements limit direct integration of app-generated data into the electronic health record, several working prototypes of provider-facing web-based dashboards have been developed, including for CBT-i Coach, PTSD Coach, PE Coach, and VetChange. Additionally, VA mobile mental health apps are designed to provide discrete elements of intervention (26,75), so that public mental health experts and providers anywhere can contribute suggestions for tools, psychoeducational content, assessments, or other features that could be readily integrated into existing applications. VA has established mechanisms for interested investigators and providers to best make use of this research and clinical infrastructure and to share suggestions or requests for collaboration (72).

ChallengesOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

There are several challenges to implementing mHealth as a means to supply evidence-based mental health interventions to those experiencing symptoms of PTSD. Privacy is a paramount concern, and VA privacy standards are extremely rigorous and do not allow for collection or sharing of personally-identifying information (76). However, many of the most commonly-used software development kits (SDKs) for mobile apps rely on companies that do not make explicit how users’ information is handled or shared. Another major challenge is that federal guidelines with respect to use of new technologies, such as cloud storage, are constantly evolving but remain behind the field, making it difficult to develop applications that can take advantage of the latest innovations in technology. Additionally, native mobile applications are difficult, costly, and require extensive human resources for initial development, maintenance, and updating. Mobile apps need to evolve over time to be responsive to providers’ and users’ expectations and needs, so the public release of a mobile app does not represent a finish line but is instead one step in a lengthy process of creating and supporting an ongoing public health resource. VA must also balance the federal mandate that its apps are fully accessible to those with auditory or visual impairments with the need to create products that are every bit as engaging and innovative as private sector mental health apps. The need for mobile apps to be fully compliant with section 508 of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and to comply with strict privacy protections makes it difficult for these apps to use many of the same features and tools that are commonplace among other apps. Finally, there remain only a limited number of trials and other studies of the use of mobile apps to deliver evidence-informed and evidence-based strategies for treating PTSD-related symptoms. Additional research is needed to better understand how to optimize mobile mental health applications for use in both self-management and treatment-companion contexts and to evaluate if such apps are having a broader public health impact.

Vision for the futureOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

From a public health perspective, mobile mental health apps offer great promise for helping to alleviate mental health disparities. Apps can be designed to meet the specific needs of populations (e.g., veterans experiencing posttraumatic stress), downloaded at low or no cost by millions of people, and used in situ at the exact moment they are needed. Apps can be used by individuals who are not connected with adequate healthcare or do not meet full criteria for a mental health diagnosis, but can also be used to support and extend EBTs. VA’s portfolio of mobile mental health apps has been widely used among VA providers, and many providers report feeling a sense of trust in these apps because they are designed to support evidence-based care, they are perceived as originating from a trustworthy and knowledgeable source, they are free to use, and they offer privacy to users. Although apps may not be the right or best solution for all unmet mental health needs, the first “generation” of mobile apps developed by the National Center for PTSD has demonstrated the utility and helpfulness of venturing into the mobile health space and providing veterans and others with an additional set of tools that can be used to address these needs. As mobile health technology has evolved, so has the potential for developing mental health apps that are engaging, effective, and impactful. For example, mobile mental health apps may be used in conjunction with virtual reality [e.g., (77)], automated conversational agents [e.g., (78)], or the apps may utilize active and passively gathered data (e.g., step count, location) to deliver tailored, context-specific interventions. If these mental health products are developed and leveraged by public health-focused agencies, they may be able to better reach underserved populations by designing engaging apps that truly meet the needs of the target population. With respect to veterans and PTSD, novel apps may be the first critical step in obtaining VA care, may be used to deliver or support evidence-based treatment, or may be a tool that helps ensure veterans and their families have the resources they need to thrive in their communities, right at their fingertips.

AcknowledgementsOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

None.

FootnoteOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ReferencesOther Section

- Introduction

- History of VA mobile mental health

- Need for public mobile mental health resources

- VA mobile mental health portfolio

- Evidence for VA mobile mental health resources

- Tailoring the portfolio to veterans and those who care for them

- Training providers in the use of mobile mental health

- Research & clinical infrastructure for mobile mental health

- Challenges

- Vision for the future

- Acknowledgements

- Footnote

- References

- Department of Health. Achieving Better Access to Mental Health Services by 2020. UK Department of Health, 2014, Available online: https://www.gov.uk/ government/publications/mental-healthservices-achieving-better-access-by-2020

- Larrison CR, Hack-Ritzo S, Koerner BD, et al. State budget cuts, health care reform, and a crisis in rural community mental health agencies. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:1255-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoagwood KE, Atkins M, Horwitz S, et al. A Response to proposed budget cuts affecting children’s mental health: Protecting policies and programs that promote collective efficacy. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69:268-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kroening-Roché J, Hall JD, Cameron DC, et al. Integrating behavioral health under an ACO global budget: Barriers and progress in Oregon. Am J Manag Care 2017;23:e303-9. [PubMed]

- Wisco BE, Marx BP, Wolf EJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the US veteran population: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans study. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:1338-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brignone E, Bundlapalli AV, Blais RK, et al. Increased health care utilization and costs among veterans with a positive screen for military sexual trauma. Med Care 2017;55:S70-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Possemato K, Wade M, Andersen J, et al. The impact of PTSD, depression, and substance use disorders on disease burden and health care utilization among OEF/OIF veterans. Psychol Trauma 2010;2:218-23. [Crossref]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Reaction. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017, Available online: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/

- Bruns EJ, Kerns SE, Pullmann MD, et al. Research, data, and evidence-based treatment use in state behavioral health systems, 2001-2012. Psychiatr Serv 2016;67:496-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levit KR, Kassed CA, Coffey RM, et al. Future funding for mental health and substance abuse: Increasing burdens for the public sector. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w513-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elpers JR. Public mental health funding in California 1959 to 1989. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1989;40:799-804. [PubMed]

- Mittal D, Drummond KL, Blevins D, et al. Stigma associated with PTSD: Perceptions of treatment seeking combat veterans. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2013;36:86-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- VA Office of Inspector General. Veterans Health Administration: Review of veterans' access to mental healthcare. Washington: VA Office of Inspector General, 2013.

- Blais RK, Renshaw KD, Jakupcak M. Posttraumatic stress and stigma in active-duty service members relate to lower likelihood of seeking support. J Trauma Stress 2014;27:116-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hester RD. Lack of access to mental health services contributing to the high suicide rate among veterans. Int J Ment Health Syst 2017;11:47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beehler GP, King PR, Vair CL, Glass J, Funderburk JS. Measurement of common mental health conditions in VHA co-located, collaborative care. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2016;23:378-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goetter EM, Bui E, Ojserkis RA, et al. A Systematic review of dropout from psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans. J Trauma Stress 2015;28:401-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee DJ, Schnitzlein CW, Wolf JP, et al. Psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Systematic review and meta-analyses to determine first-line treatments. Depress Anxiety 2016;33:792-806. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haagen JF, Smid GE, Knipscheer JW, et al. The Efficacy of recommended treatments for veterans with PTSD: A metaregression analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2015;40:184-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenheck RA, Fontana AF. Recent trends in VA treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental disorders. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:1720-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spoont MR, Murdoch M, Hodges J, et al. Treatment receipt by veterans after a PTSD diagnosis in PTSD, mental health, or general medical clinics. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:58-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norris FH, Slone LB. The epidemiology of trauma and PTSD. In Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA (eds). Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice. Guilford Press, New York, 2012; 78-98.

- Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Washington: VA/DoD, 2017;15.

- Pew Research Center. Mobile fact sheet. Pew, 2018, Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/

- Edwards-Stewart A, Smolenski DJ, Reger GM, et al. An analysis of personal technology use by service members and military behavioral health providers. Mil Med 2016;181:701-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoffman J, Kuhn E, Owen JE, et al. Mobile Apps to improve outreach, engagement, self-management, and treatment for PTSD. In: Benedek D, Wynn G, eds. Complementary and Alternative Medicine for PTSD. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Erbes CR, Stinson R, Kuhn E, et al. Access, utilization, and interest in mHealth applications among Veterans receiving outpatient care for PTSD. Mil Med 2014;179:1218-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witt K, Spittal MJ, Carter G, et al. Effectiveness of online and mobile telephone applications (“apps”) for the self-management of suicidal ideation and self-harm: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:297. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mantani A, Kato T, Furukawa TA, et al. Smartphone cognitive behavioral therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for refractory depression: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2017;19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horsch CH, Lancee J, Griffioen-Both F, et al. Mobile phone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A randomized waitlist controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2017;19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhn E, Kanuri N, Hoffman JE, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the PTSD Coach app with community trauma survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:267-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim J, Lim S, Min YH, et al. Depression screening using daily mental health ratings from a smartphone application for breast cancer patients. J Med Internet Res 2016;18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhn E, Weiss BJ, Taylor KL, et al. CBT-I Coach: A description and clinician perceptions of a mobile app for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12:597-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller KE, Kuhn E, Owen JE, et al. Clinician perceptions related to the use of the CBT-I Coach mobile app. Behav Sleep Med 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang W, Kreindler D. Supporting homework compliance in cognitive behavioural therapy: Essential features of mobile apps. JMIR Ment Health 2017;4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. FY 2018-2024 Strategic Plan. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, D.C., 2018.

- National Health Service. NHS Apps. NHS England, 2018, Available online: https://apps.beta.nhs.uk

- Lehavot K, Der-Martiorasian C, Simpson TL, et al. Barriers to care for women veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and depressive symptoms. Psychol Serv 2013;10:203-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman D, Sheaves B, Goodwin GM, et al. The effects of improving sleep on mental health (OASIS): A randomized controlled trial with mediation analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:749-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sunyaev A, Dehling T, Taylor PL, et al. Availability and quality of mobile health app privacy policies. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:e28-33. [PubMed]

- Erfani Joorabchi M, Mesbah A, Kruchten P. Real challenges in mobile app development. Proc ACM-IEEE Int Symp Empirical Software Engineer Measurement 2013;2013:15-24.

- Zhechao Liu C, Au YA, Seok Choi H. Effects of freemium strategy in the mobile app market: An empirical study of Google Play. J Management Inform Systems 2014;31:326-54. [Crossref]

- Bakker D, Kazantzis N, Rickwood D, et al. Mental health smartphone apps: Review and evidence-based recommendations for future developments. JMIR Ment Health 2016;3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huckvale K, Prieto JT, Tilney M, et al. Unaddressed privacy risks in accredited health and wellness apps: A cross-sectional systematic assessment. BMC Med 2015;13:214. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhn E, Greene C, Hoffman J, et al. Preliminary evaluation of PTSD Coach, a smartphone app for post-traumatic stress symptoms. Mil Med 2014;179:12-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miner A, Kuhn E, Hoffman JE, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of the PTSD Coach app: A pilot randomized controlled trial with community trauma survivors. Psychol Trauma 2016;8:384-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cancer Distress Coach Mobile App, unpublished data. Duke Cancer Institute, 2018, Available online: http://www.dukecancerinstitute.org/distresscoach

- Keen SM, Roberts N. Preliminary evidence for the use and efficacy of mobile health applications in managing posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Health Systems 2017;6:122-9. [Crossref]

- Owen JE, Jaworski B, Kuhn E, et al. mHealth in the wild: Using novel data to examine the reach, use, and impact of PTSD Coach. JMIR Ment Health 2015;2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reger GM, Skopp NA, Edwards-Stewart A, et al. Comparison of prolonged exposure (PE) coach to treatment as usual: A case series with two active duty soldiers. Mil Psychol 2015;27:287-96. [Crossref]

- Babson KA, Ramo DE, Baldini S, et al. Mobile app-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: Feasibility and initial efficacy among veterans with cannabis use disorders. JMIR Res Protoc 2015;4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koffel E, Kuhn E, Petsoulis N, et al. A pilot study of CBT-I Coach: Feasibility, acceptability, and potential impact of a mobile app for patients in cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Health Informatics J 2018;24:3-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McFall M, Saxon A, Malte C, et al. Integrating tobacco cessation into mental health care for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:2485-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hicks TA, Thomas SP, Wilson SM, et al. A preliminary investigation of a relapse prevention mobile application to maintain smoking abstinence among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Dual Diagn 2017;13:15-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbst E, Pennington D, Kuhn E, et al. Mobile technology to promote smoking cessation treatment engagement in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Prev Med 2018;54:124-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Possemato K, Johnson E, Hoffman JE, et al. Clinician-supported PTSD Coach: Provider and patient input on acceptability and barriers and facilitators to implementation. Transl Behav Med 2017;7:116-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Possemato K, Kuhn E, Johnson E, et al. Using PTSD Coach in primary care with and without clinician support: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;38:94-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhn E, Eftekhari A, Hoffman JE, et al. Clinician perceptions of using a smartphone app with prolonged exposure therapy. Adm Policy Ment Health 2014;41:800-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuhn E, Crowley JJ, Hoffman JE, et al. Clinician characteristics and perceptions related to use of the PE (Prolonged Exposure) Coach mobile app. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2015;46:437-43. [Crossref]

- Reger GM, Browne K, Campellone T, et al. Barriers and facilitators to mobile application use during PTSD treatment: Clinician use of PE Coach. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2017;48:510-7. [Crossref]

- Matheson GO, Pacione C, Shultz RK, et al. Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:472-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harte R, Quinlan LR, Glynn L, et al. Human-centered design study: Enhancing the usability of a mobile phone app in an integrated falls risk detection system for use by older adult users. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017;5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown T, Wyatt J. Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2018, Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/design_thinking_for_social_innovation

- Vechakul J, Shrimali BP, Sandhu JS. Human-centered design as an approach for place-based innovation in public health: A case study from Oakland, California. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:2552-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Owen JE, Jaworski BK, Kuhn E, et al. Development of a mobile app for family members of veterans with PTSD: Identifying needs and modifiable factors associated with burden, depression, and anxiety. J Fam Stud 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref]

- Stirman SW, Gutner CA, Langdon K, et al. Bridging the gap between research and practice in mental health service settings: An overview of developments in implementation theory and research. Behav Ther 2016;47:920-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pittman D, Blatt A, McGraw K. Practice-Based Implementation Network: Creation and Sustainment of an Enterprise-Wide Implementation Science Initiative for Psychological Health Evidence-Based Practices. The Mil Psychol 2017;32:18-20.

- Schueller SM, Washburn JJ. Price. Exploring mental health providers' interest in using web and mobile-based tools in their practices. Internet Interv 2016;4:145-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gagnon MP, Ngangue P, Payne-Gagnon J, et al. m-Health adoption by healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016;23:212-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramsey A, Lord S, Torrey J, et al. Paving the way to successful implementation: identifying key barriers to use of technology-based therapeutic tools for behavioral health care. J Behav Health Serv Res 2016;43:54-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armstrong CM, Edwards-Stewart A, Ciulla RP, et al. U.S. Department of Defense Mobile Health Practice Guide, 3rd edition. U.S. Department of Defense, Joint Base Lewis-McChord, 2017.

- Hoffman JE, Ramsey K, Taylor KL. Mobile behavior design lab: Apps. National Center for PTSD, Dissemination & Training Division, 2018. Available online: http://myvaapps.com

- Anthes E. Pocket psychiatry: Mobile mental-health apps have exploded onto the market, but few have been thoroughly tested. Nature 2016;532:20-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fleming E, Crawford EF, Calhoun PS, et al. Veterans’ preferences for receiving information about VA services: Is getting the information you want related to increased health care utilization? Mil Med 2016;181:106-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohr DC, Schueller SM, Montague E, et al. The Behavioral Intervention for Technology Model: An Integrated conceptual and technological framework for eHealth and mHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res 2014;16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- VA Handbook 6500: Risk management framework for VA information systems. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018, Available online: https://www.va.gov/vapubs/viewPublication.asp?Pub_ID=793&FType=2

- Rizzo A, Cukor J, Gerardi M, et al. Virtual reality exposure for PTSD due to military combat and terrorist attacks. J Contemp Psychother 2015;45:255-64. [Crossref]

- Fitzpatrick KK, Darcy A, Vierhile M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot): A randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 2017;4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Owen JE, Kuhn E, Jaworski BK, McGee-Vincent P, Juhasz K, Hoffman JE, Rosen C. VA mobile apps for PTSD and related problems: public health resources for veterans and those who care for them. mHealth 2018;4:28.