Parent preferences for text messages containing infant feeding advice

Introduction

Pediatric obesity is a worldwide epidemic affecting the lives of more than 43 million preschool-aged children (1). Almost 18.5% of children aged 2–19 are currently classified as obese (2). Pediatric obesity is a critical issue because it can result in many comorbid conditions. Early childhood obesity is a particular problem because of the increased risk of obesity as an adult and higher morbidity and mortality rates (3).

In the US, risk factors for obesity in children include being a racial or ethnic minority, from single parent-headed households with lower educational attainment, living in poverty, having never been breastfed, and engaging in higher amounts of screen time (2). Factors related to early rapid weight gain and early obesity include parental obesity, birth weight, lack of breastfeeding, early cessation of breastfeeding, lack of parental knowledge about child nutrition, and early introduction of solids (2,4,5). Because some of these factors are not modifiable, adoption of obesity-protective parental feeding practices such as breastfeeding, avoiding sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs), appropriate introduction of first foods, and responsive feeding is especially important (1). Healthy school lunch initiatives, physical activity programs, family-based treatment programs, and many other programs have been implemented in an attempt to reduce pediatric obesity (6). Some of these programs have been successful. Yet, despite years of obesity prevention, rates of childhood obesity are still increasing (3). Thus, other prevention methods are needed to reverse this trend.

Mobile health (mHealth) programs are among the most recent initiatives employed in several areas to promote health (7). mHealth is the use of wireless and mobile technology to address health priorities (7). mHealth can include health information delivered via text message, social media apps, emails, and calls from a health provider with health information (8,9). These types of communication have been tested for various groups, and the use of text messages, in particular, has recently started to gain traction (7-9).

As mobile phone use has increased globally in recent years, mHealth has become viable in many groups, including in low income patients. This health promotion strategy has the potential to change health care delivery around the world as patients need convenient access to health resources. mHealth can be used to provide credible health information to patients at an affordable cost, which makes it potentially useful in preventing pediatric obesity. There are many gaps in the mHealth and text messaging literature, and it is unclear the frequency, timing, and type of message (gain- vs. loss-framed) that best promotes healthy infant feeding practices. Gain-framed messaging can be described as positive messages showing the benefits of taking a certain action (10). In contrast, loss-framed messaging is negative, with an emphasis on the disadvantages that may result from a certain action. However, there is very limited literature exploring the use of framing in text messaging (11). The aim of this study was to determine the optimal time, frequency, and type of text message that parents of newborns would like to receive regarding feeding methods.

Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional on-line survey. Participants were parents of infants aged birth to three months recruited during well child visits with their infant’s health care provider in an urban clinic in Fort Worth, Texas, USA, the University of North Texas Health Science Center (UNTHSC) Pediatric Clinic. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of UNTHSC (Project Number: 2018-102) and authorized by the IRB at Texas Woman’s University (TWU).

Participants and recruitment

Participants were invited to participate by research staff or their infant’s healthcare provider. Flyers were also posted in the waiting area. Parents 18 years or older of full-term infants who established care with the healthcare provider before 3 months of life were eligible to participate. Parents who were younger than 18 years of age, who established care with the healthcare provider after 30 days of life, and parents of pre-term infants (born <37 weeks) or infants with congenital anomalies or genetic disorders were excluded. Parents younger than 18 were excluded because researchers suspected that the teen parents’ concerns regarding feeding and sources of feeding advice might be different compared to adult parents.

Instrument development

The survey was developed by the first author with input from two qualified professionals, a registered dietitian, and a certified health education specialist. The Health Belief Model (HBM) served as the theoretical framework. Each question set was based on one key HBM construct and a targeted healthy feeding practice (see Table 1). These constructs included perceived susceptibility to early pediatric obesity, perceived benefits and barriers to breastfeeding, cues to action for complementary feeding (introduction of solids), and breastfeeding self-efficacy.

Full table

Survey procedures

The survey was administered electronically using PsychData as the platform. Interested parents were able to access the survey on their own mobile devices by typing in a shortened URL linking to the survey. Parents could complete the survey during the clinic visit or later. Upon accessing the survey, parents reached an entry page that explained the purpose of the survey, provided a contact person for questions and problems, and notified participants that clicking “proceed” served as their consent to participate in the survey. Incentives for participants who completed the survey included feeding items such as sippy cups.

Each participant reviewed two sets of sample text messages aimed at influencing one of the HBM constructs identified as a target for a future early pediatric obesity prevention intervention. Each sample text message was presented two ways: one gain-framed, one loss-framed. Messages were presented in sets (all gain-framed messages together and all loss-framed together) with questions regarding preferred frequency and time of day for receiving text messages presented between the sets. The order in which participants received the messages was changed at random. At the end of the survey, participants answered demographic questions about languages spoken at home, parent age, number and ages of children, and participation in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Parents were also asked to report their own height and weight. Sixteen participants received the gain-framed questions before the loss-framed questions, and 18 participants received the loss-framed questions first.

As each sample text message was presented, participants were asked to rate how much they agreed with the statement “This message is helpful to me” using a 1–5 Likert scale (1= very likely and 5= very unlikely). Participants also rated how likely each message was to influence their adoption of a healthy feeding practice and were invited to provide open-ended feedback about the message. After parents evaluated one set of messages (gain- or loss-framed) and answered questions regarding preferred frequency and timing, participants evaluated another set of messages.

Data analysis

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9 to determine the minimum sample size required to find significance with a desired level of power set at 0.80, an alpha (α) level at 0.05, and a moderate effect size of 0.60 (d) (12,13). Based on the analysis, it was determined that a minimum of 24 participants were required to ensure adequate power for the paired-samples t-test. However, researchers aimed for 40 participants to elicit a variety of survey responses.

Descriptive and frequency analyses were applied to the demographic survey questions and questions regarding preferred time of day and days of the week to receive text messages. Variables were computed for gain-framed and loss-framed message helpfulness scores and for likelihood of each message set to affect feeding practices. To identify the style of message preferred by parents, paired samples t-test were used to compare helpfulness scores and likelihood of affecting feeding practices between gain-and loss-framed messages. The impact of order of message style presentation was analyzed by comparing the means of the two groups with an independent samples t-test. In addition, researchers analyzed open-ended questions using open coding to generate key themes.

Results

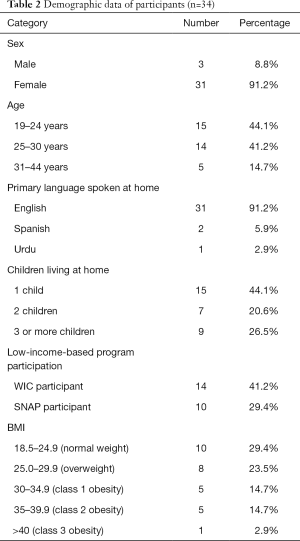

A total of 34 parents (31 mothers and 3 fathers) completed the survey, taking an average of 13 minutes to complete it. Participants were 26±5.5 years old. Ten participants (29%) reported they received SNAP benefits, and 14 (41%) received WIC benefits. Fifteen of the participants (44%) had only one child at home. A race/ethnicity question was not included in the survey; however, in response to a question about languages spoken at home, two out of the 34 participants stated Spanish was the primary language spoken at home. Ten participants (30%) spoke Spanish as their first or second language (Table 2).

Full table

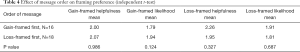

Overall, 56% of participants “strongly agreed” or “agreed” the gain-framed messages were helpful. Sixty-five percent of participants indicated they were “somewhat likely”, or “very likely” to adopt feeding practices based on the gain-framed messages. By comparison, almost the same percentage of participants (53%) “strongly agreed” or “agreed” the loss-framed messages were helpful. Exactly the same percentage (65%) of participants also indicated they were “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to engage in the practice based on the loss-framed messages. In comparing individual gain-framed vs loss-framed messages using paired t-tests, there was no overall difference in helpfulness scores (how much participants agreed that the message was “helpful to me”) or likelihood scores (perceived likelihood of adopting the practice) (Table 3). In comparing parental responses to determine whether order of presentation affected scores, an independent samples t-test revealed no difference (Table 4).

Full table

Full table

When individual pairs addressing each construct of the HBM were compared, the gain-framed messages relating to breastfeeding benefits and breastfeeding self-efficacy for breastfeeding were viewed as more helpful compared to the loss-framed messages (mean difference =−0.441, P=0.034 and mean difference =−0.412, P=0.041, respectively) (Table 3). There were no differences between individual pairs in terms of likelihood to adopt feeding practices (Table 5).

Full table

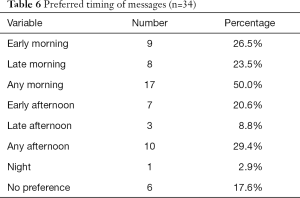

The majority of participants (38%) indicated they preferred to receive text messages once during the week, while 29% elected for one time per month, and 14.7% preferred one to two times per week. Half of participants preferred morning messages, as opposed to afternoon or evening (Table 6).

Full table

Five participants gave comments on how to revise the statements. All of these comments addressed the statements regarding breastfeeding. For pair one regarding breastfeeding benefits, one participant wanted a daily reminder and thought it “would be taken offense by a non-breastfeeding mom.” Another participant added that having a message that “starts with breastfeeding has positive effects” would be better. With regard to the gain-framed statement regarding barriers to breastfeeding, one participant thought that the message was “very disrespectful to the moms who can’t.” For pair four, promoting breastfeeding self-efficacy, one participant thought that the message was comparing all women without understanding that everyone is different. One participant commented that the loss-framed version of the breastfeeding self-efficacy statement sounded “harsh”. One participant included a comment that linking to a study on a particular topic would be beneficial.

Discussion

Parents of infants had no strong preferences between gain- or loss-framed text messages regarding infant feeding practices. For most question pairs, helpfulness scores did not differ. Parents also did not perceive gain-framed messages as more likely to cause them to adopt a feeding practice compared to loss-framed messages. However, gain-framed messages relating to the HBM constructs of perceived benefits and self-efficacy for breastfeeding were viewed as more helpful. Thirty-eight percent of participants preferred receiving messages once per week, and 50% preferred morning messages. Parents indicated they were interested in receiving messages from their child’s health care provider related to feeding. Overall results suggest text messaging may be a promising practice in pediatric primary care.

This study’s findings are somewhat different from other research findings indicating gain-framed messages may be more helpful in getting participants to adopt prevention-oriented behaviors compared to loss-framed messages (10,14,15). It is possible that this small sample of messages was not a large enough pool to elicit a difference in response to framing. It is also possible that parents were happy to receive feeding advice and thus did not mind the approach to providing information, unless it was on a sensitive subject, such as breastfeeding. This is the first research of which we are aware to address parental preferences for frequency and timing of receiving text messages regarding infant feeding practices.

Strengths of this research include the diversity of the population, which included about 30% Spanish-speaking participants and a high percentage of lower socioeconomic status participants, as shown by higher SNAP and WIC participation rates (29% and 41%, respectively). These populations are more at risk for early pediatric obesity (16), thus representing a potential target population for an intervention to prevent early obesity. The tested text messages were developed by health professionals with a strong background in health prevention, nutrition education, and pediatric nutrition. The messages themselves were theoretically-based on the HBM, which was chosen after completing focus group research in the same clinic population to explore parental views on infant feeding practices, causes of early pediatric obesity, and preferences for communication with their infants’ healthcare providers (17).

The study had limitations as well. In the current study participants indicated their language preference, but not their race/ethnicity, making it impossible to assess accurately the impact of race/ethnicity on framing preference. This is relevant because it was shown in one study that white Americans are more receptive to change a behavior when a health message is loss-framed, while African Americans may be more receptive to taking specific action when a message is gain-framed (18).

Another limitation is our inability to assess accurately how closely the sample fits the overall demographic pattern in the US, Texas, and in the clinic itself. In the United States, the Hispanic population accounts for 18.1% of the total population (19); whereas in Texas, the Hispanic population accounts for roughly 39% of the total state population (20). While race/ethnicity was not assessed in the current study, about 30% of the study participants spoke Spanish in their home as either their primary or secondary language, indicating this sample may be similarly diverse with regard to Hispanic ethnicity compared to the population in Texas.

Other limitations include the small sample size from a single clinic. In order to increase the generalizability of the results, a larger sample size would be helpful to examine more question sets comparing perceptions about theoretically-based gain- versus loss-framed messages, particularly regarding whether certain characteristics, such as SES, race/ethnicity, or BMI status, affects preferred message framing. In addition, more message sets may have produced better understanding of preferred message framing among parents of infants.

Based on this study’s findings, there are practical implications to consider. For example, when developing a text message-based intervention program for parents of infants, it may be beneficial to have a variety of gain and loss-framed messages. Sending one to two messages per week, primarily in the morning, may be helpful. It is important to avoid overwhelming parents with too many messages, and some parents are receptive to receiving text messages with links to more information. It is also prudent to avoid messages that may be perceived as aggressive or cause offense. Nevertheless, other parents of infants may have different message preferences. Thus, it is important to pretest text messages with the target population to help ensure that the health messages are transmitted and received efficaciously. This study should prove helpful in that regard, in informing development of an intervention for this particular clinic population. It is also important to keep in mind that a text message-based intervention in Texas or in this clinic may need to be different from interventions designed for other populations.

This study suggests several potential avenues for future research. Further research is necessary to better understand the role of culture and text-messaging preference among parents of infants. Future studies should include race and ethnicity in the demographic assessment, which will help researchers examine the relationship between race/ethnicity and framing preference. A study of a larger, diverse population of parents testing a greater number of theory-based messages may be helpful in verifying whether message framing should be an important focus when developing a text-message based health promotion intervention for parents of infants.

Conclusions

From a broader perspective, health promotion interventions incorporating text messaging will likely become increasingly common. mHealth interventions have the potential to reach diverse populations in the US and globally as mobile phone use has become ubiquitous among adults within varying demographics (21). The current study adds to the knowledge base concerning mHealth, the use of text messaging to prevent early pediatric obesity, and parents’ preferences regarding message framing, as well as the optimal frequency and timing of messaging. In particular, this study provides insight into parents’ preferences on receiving text messages from their child’s healthcare provider concerning infant feeding practices. Findings showed that parents did not have a strong preference for either gain- or loss-framed messages, except possibly with regard to breastfeeding. Overall, this study revealed that parents find text messaging and mHealth beneficial for themselves and their children. Therefore, text messaging may be a viable mHealth option in preventing early pediatric obesity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Paul Bowman, MD, the Chair of the Pediatric Clinic at UNTHSC for his support of this project. They would also like to acknowledge Leah Zimmerman for her invaluable assistance in navigating the IRB process and supporting recruitment and provision of incentives to parents of infants. Finally, they would like to acknowledge Paul Yeatts, at the Center for Research Design and Analysis at TWU for his assistance with the survey design, implementation, and statistical analysis. This work was supported by the TWU Human Nutrition Research fund.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of UNTHSC (Project Number: 2018-102) and authorized by the IRB at TWU.

References

- Pietrobelli A, Agosti M. Nutrition in the First 1000 Days: Ten Practices to Minimize Obesity Emerging from Published Science. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States: 2015-2016. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief 288, October 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf

- Roth CL, Jain V. Rising Obesity in Children: A Serious Public Health Concern. Indian J Pediatr 2018;85:461-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pluymen LP, Wijga A, Gehring U, et al. Early introduction of complementary foods and childhood overweight in breastfed and formula-fed infants in the Netherlands: the PIAMA birth cohort study. Eur J Nutr 2018;57:1985-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wasser HM, Thompson AL, Suchindran CM, et al. Family-based obesity prevention for infants: Design of the “Mothers & Others” randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2017;60:24-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, et al. What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and metaetaand metaObes Reviews 2015;16:547-65.

- Garner SL, Sudia T, Rachaprolu S. Smart phone accessibility and mHealth use in a limited resource setting. Int J Nurs Pract 2018;24:e1260. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Callender C, Thompson D. Text Messaging Based Obesity Prevention Program for Parents of Pre-Adolescent African American Girls. Children (Basel, Switzerland) 2017;4:105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen S, Gong E, Kazi DS, et al. Using Mobile Health Intervention to Improve Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Diseases in China: Mixed-Methods Feasibility Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2018;6:e9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wansink B, Pope L. When do gain-framed health messages work better than fear appeals? Nutr Rev 2015;73:4-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavey Louisa, Churchill Sue. Promoting the Avoidance of High-Calorie Snacks: Priming Autonomy Moderates Message Framing Effects. PLoS One 2014;9:e103892. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using GPower 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, et al. GPower 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chien YH, Chang WT. Effects of message framing and exemplars on promoting organ donation. Psychol Rep 2015;117:692-702. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhynders PA, Sayers CA, Presley RJ, et al. Providing young women with credible health information about bleeding disorders. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:674-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rogers R, Eagle TF, Sheetz A, et al. The Relationship between Childhood Obesity, Low Socioeconomic Status, and Race/Ethnicity: Lessons from Massachusetts. Child Obes 2015;11:691-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell A. Conversations with parents of infants: opinions on best ways to feed and prevent obesity. [Master’s thesis]. Denton, TX: Texas Woman’s University; 2019.

- Lucas T, Hayman LW, Blessman JE, et al. Gain versus losssus lossal. Gain versus lossons on best ways to feed and prevent obesitns: A preliminary examination of perceived racism and culturally targeted dual messaging. British Journal of Health Psychology 2016;21:249-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- U.S Census Bureau QuickFacts: Texas. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/tx. Accessed March 19, 2019.

- Hispanic Heritage Month 2018. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2018/hispanic-heritage-month.html

- Ramirez V, Johnson E, Rossetti G. Assessing the Use of Mobile Health Technology by Patients: An Observational Study in Primary Care Clinics. JMIR MHealth Uhealth 2016;4:e41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Brown C, Davis KE, Habiba N, Massey-Stokes M, Warren C. Parent preferences for text messages containing infant feeding advice. mHealth 2020;6:9.