Patient clinical documentation in telehealth environment: are we collecting appropriate and sufficient information for best practice?

Introduction

When the COVID-19 pandemic public health emergency (PHE) created a practical distance between providers and those seeking care, even if they weren’t geographically distant, telehealth became a viable solution to providing patient care (1). The COVID-19 pandemic led to patient fear of being exposed to the virus when visiting healthcare facilities as well as healthcare providers’ fears of becoming infected by their patients (2-4). These feelings led to the disruption of the customary face-to-face and bedside approach to patient care (1-3). The surge of telehealth usage during the pandemic elevates the importance and demand for better clinical documentation. When accomplished, this will benefit patient care, reimbursement requirements, and data-driven decision-making processes.

Even though telehealth services have been around for several decades, utilization rates have remained low (5). Since 2020, healthcare providers have eagerly embraced the use of telehealth services due to the extended lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (4). During the PHE this past year, the number of telehealth visits increased dramatically (4,6,7). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reports 68 million telehealth services were delivered between March and October 2020, an increase of more than 2,700% compared to the same period from 2019 (8). The Fair Health Organization, which reports on private insurance, not including Medicare and Medicaid, reported an even more striking increase in telehealth claims, with only 0.17% telehealth claims in March 2019, compared to 7.52% of telehealth claims in March 2020, a surge increase of 4,346.94% nationally (9). Due to the urgent need to transition from in-person office visits to a virtual online care model, physician offices experienced many difficulties related to rapid technology implementation, changes in documentation practices, and other challenges (1,3,7).

In March 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded telehealth coverage for all Medicare and Medicaid patients during the COVID-19 pandemic (10,11). This required healthcare providers to integrate new practices in their office management processes, such as scheduling, triage, and billing for telehealth sessions into their regular on-site procedures (4). To understand and follow documentation guidelines, physicians, coding and billing staff alike rushed to learn how to choose the appropriate Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and modifiers for reimbursement of telehealth encounters (7,12). The unplanned tsunami of telehealth visits and the enormous increase in submission of claims for reimbursement attracted a great deal of attention from all payors and especially the Office of Inspector General (OIG). This increase in claims submission has led to increased scrutiny by payors and oversight agencies regarding the appropriate and accurate documentation required for telehealth visits (10,13).

Documentation needs for telehealth visits differ from traditional in-office visits in a variety of ways. To ensure appropriate payment, the following documentation elements should be captured for a telehealth visit (7,13):

- Date of the visit.

- Consent for visit from patient or patient representative (verbal or written).

- Category for office visit—real-time audio with video or audio/telephone only.

- Date the patient was last seen or was billed for correspondence to avoid date overlap with other billable services.

- Patient location for the visit.

- Provider location for the visit.

- Names and roles of all participants.

- Start time and end time for telehealth encounter (length of time billing provider spent on the day of the visit and how time was spent if billing by time or a time-based code).

Consistent collection and management of specific details such as the location of the patient and the provider, communication mode and length of telehealth visit along with appropriate templates to enable proper clinical documentation for telehealth services can reduce denials and lagging payers (7,2). Many agencies are vested in ensuring that payment for these visits is accurate (13,14). CMS also continues to revise and finalize the changes to the physicians’ fee schedule based on the COVID-19 PHE (14).

Although virtual visits were not in high demand before the COVID-19 pandemic, the capability to provide services in that mode was well-established within the healthcare delivery system. Patients have reported a high degree of satisfaction regarding the quality and convenience of care (4,15). The expansion of telehealth coverage has increased patient satisfaction with telehealth services (15). Patients’ clear enthusiasm for flexible care options demonstrates a true need for further innovative ways to deliver healthcare. Barriers remain, including Internet capacity (Wi-Fi and bandwidth), reimbursement, licensure, trained personnel, and technology costs as well as evidence-based use in all areas of healthcare. However, telehealth may be a solution for healthcare providers to deliver timely access to services, increase access to local providers including specialties, and improve choices for patients (4,5).

This study aimed to assess telehealth use during the COVID-19 pandemic, evaluate completeness and type of clinical documentation used and collected in telehealth practice; identify challenges and issues encountered when using telehealth for patient visits; and develop a strategy for best practice for telehealth clinical data documentation and data management.

We present the following article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-30).

Methods

Study participants and survey procedure

A cross-sectional descriptive internet-based survey study was conducted through web online delivery and data collection. Survey questionnaires were distributed through Qualtrics in January and February 2021 to all active members from Mid-Atlantic Telehealth Resources Center and Missouri Medical Group Management Association (Missouri MGMA). This study was not human subject research, and we collected only facility data. Therefore, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required. The survey was targeted to office managers and administrators from healthcare facilities that were current or past telehealth users. Individuals who received the survey emails were instructed to answer the survey if they were office managers or administrators or forward the survey email message to any appropriate individuals in their office or health facilities. Only one respondent from each facility was allowed to answer the survey. This is a self-selected internet sample; the total potential responses of this web-based survey delivery were unknown. Those individuals who were interested and eligible could agree to the consent and to participate by clicking on the survey link included in the email. The responses from the survey were anonymous to ensure confidentiality. A follow-up reminder was sent two weeks after the initial survey using the same procedures as the initial survey distribution.

Survey design and measurements

In aligning with the purpose of the study, a survey was developed based on information gathered from the literature and website review. The researchers consolidated, designed, and confirmed each question to ensure the clarity, accuracy, and validity of the questionnaire.

The components of the survey fell into four categories: (I) Health organization demographic information (current position, type, size, and location of healthcare facilities); (II) Telehealth visit usage (time started using telehealth for patient visits, type of patient care provided by telehealth visits, telehealth service methods used, telehealth policy, procedure and training used); (III) Clinical documentation collected for telehealth visits (type of clinical documentation, responsible party for the collection of telehealth documentation, purpose of telehealth data use, methods used for documentation of telehealth visits); and (IV) Challenges and barriers related to telehealth use and documentation.

In this study, we defined “healthcare providers” as physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners; “medical staff” included primary care physicians, nonsurgical specialty physicians, surgical specialty physicians, non-physician medical staff, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. We selected our cutoff date for the COVID-19 pandemic as before and after March 2020.

A pilot test was performed before the final survey was distributed. Eleven (11) managers from the physician's offices were asked to complete the online survey, following the same procedures from the study design. The feedback received from the pilot test related to both the content and technical aspects of the survey, as well as the time needed to complete the survey. This information was used to make necessary revisions to the final survey. The estimated time for completing each survey was 10 minutes.

Data analysis and statistical analysis

The survey was distributed and administered through Qualtrics. The data were analyzed using qualitative data analysis techniques and basic descriptive statistics for the numerical (frequency counts) data collected. We used Excel and Qualtrics for frequency distributions to describe the results with tables and graphs identifying the discrete variables. The percent of the increase was used to describe the differences in telehealth visits over the specific time frame. Missing values were excluded from the item analyses.

Results

Health organization characteristics

There were 76 total responses to the survey. Not every question was answered by all respondents which resulted in fewer than 76 responses on various questions. Some questions asked the respondents to select all applicable options, resulting in more than 76 items selected for those questions.

Respondents were asked to select the job title that best described their current role. A large majority (75%) of the respondents were manager and administrator, coordinator (11%), health care providers (10%), and the remaining 4% were grouped into an “Other” category. Half of the respondents reported working in a physician practice setting (50%), while other settings included behavioral/mental health (22%) and outpatient services (16%). The range of reported number of healthcare providers, including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners in these organizations spanned from 1 to 1,700. Three respondents reported over 100 providers in their healthcare facilities with outliers of 207, 620, and 1,700. The median number of providers per practice was six, and the most reported or mode was five providers on-site.

Individuals from 11 states responded to the survey; the top three states with the most respondents were from North Carolina (55%), Missouri (20%), and West Virginia (12%). More than half of the respondents’ workplace was located in a rural area (54%), followed by suburban (25%), and urban settings (21%).

Telehealth visits

Of 76 respondents, 75 (99%) indicated their facility currently uses or has in the past used telehealth for patient visits; those respondents were invited to answer the remaining questions in the survey. Of those facilities providing telehealth services, 62% had been offering telehealth for less than 1 year, 18% had been using telehealth for between 1–4 years, and 20% had been utilizing telehealth for 5 years or more, as displayed in Table 1. In comparing telehealth offerings before and after March 2020, when prevention measures were undertaken in the United States to address the spread of COVID-19, 94% of respondents indicated their facility had experienced an increase in telehealth visits. Only 54 of the 71 respondents’ facilities who offered telehealth had been doing so before March 2020. The results are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1

| Telehealth use timeframe | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year | 44 | 62 |

| 1−4 years | 13 | 18 |

| 5 or more years | 14 | 20 |

| Total | 71 responses |

Table 2

| Changes in telehealth use | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Increased use | 51 | 94 |

| Decreased use | 2 | 4 |

| Stayed the same | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 54 responses |

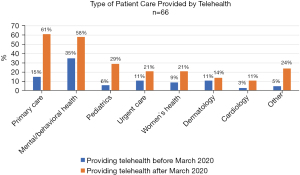

Respondents also were asked about the types of patient care for which telehealth was used. Prior to March 2020, Mental and Behavioral Health used telehealth services most frequently (35%) followed by Primary Care (15%). Respondents indicated that the use of telehealth after March 2020 increased for each specialty included in the survey. Primary Care was the area in which telehealth was used most frequently (61%) after March 2020, Mental and Behavioral Health was also commonly used (58%), as was Pediatrics (29%). Increases in these areas as well as other areas can be seen in Figure 1. Each respondent was asked to indicate all types of care in their facilities for which telehealth was used.

Healthcare facilities utilized multiple methods to reach patients for telehealth visits. Telehealth-specific applications were the most reported method of delivering telehealth at 79%, while 63% of respondents utilized non-telehealth programs such as Zoom, Facetime, or other web conferencing. Telephone-only and patient portal messaging was also used by over half of the respondents.

Respondents provided information about telehealth policies used in their organization. In-house designed written guidelines were the most frequently used policies (71%), while governmental (57%), third-party payor (39%), and professional association (35%) guidance were also reported. Ten percent of respondents indicated they did not use any specific telehealth guidelines or policies.

Data regarding the types of telehealth training and resources provided to clinical providers and/or non-clinical staff were collected. Options included technical, clinical documentation, billing/reimbursement, legal/regulatory, other training, or no specific training. Results of the 68 respondents are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3

| Training type, n=68* | For clinical providers, n [%] | For non-clinical staff, n [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Technical (equipment and software) | 60 [88] | 49 [72] |

| Clinical documentation | 58 [85] | 32 [47] |

| Billing and reimbursement | 39 [57] | 46 [68] |

| Legal and regulatory (security, HIPAA, risk management) | 48 [71] | 44 [65] |

| Other training | 5 [7] | 5 [7] |

| No training or resources provided | 2 [3] | 2 [3] |

*, a total number of 68 facilities who can select both Clinical and Non-Clinical.

Clinical documentation for telehealth visits

Respondents were asked how frequently various types of documentation were collected (manually or electronically) on patient telehealth visits at their healthcare facility. A scale was used indicating the frequency; 1-never, 2-rarely, 3-sometimes, 4-often, and 5-always. Results are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4

| Documentation, n=54 | Never, n [%] | Rarely, n [%] | Sometimes, n [%] | Often, n [%] | Always, n [%] | Total responses* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient identification number | 10 [20] | 1 [2] | 0 | 0 | 40 [78] | 51 |

| Patient location | 6 [11] | 2 [4] | 7[13] | 5 [9] | 34 [63] | 54 |

| Provider location | 7 [13] | 3 [6] | 3 [6] | 6 [11] | 35 [64] | 54 |

| Communication method (by Telehealth, phone, patient portal) | 1 [2] | 0 | 0 | 11 [21] | 41 [77] | 53 |

| Date of service | 1 [2] | 0 | 0 | 2 [4] | 51 [94] | 54 |

| Start and stop time | 4 [8] | 6 [11] | 10 [19] | 5 [9] | 28 [53] | 53 |

| Referring physician | 14 [26] | 5 [10] | 10 [19] | 7 [13] | 17 [32] | 53 |

| Consulting physician | 14 [27] | 4 [8] | 9 [18] | 8 [16] | 16 [31] | 51 |

| Patient informed consent | 4 [7] | 1 [2] | 4 [7] | 5 [10] | 40 [74] | 54 |

| Any other providers involved, or individuals present | 8 [16] | 2 [4] | 7 [14] | 15 [29] | 19 [37] | 51 |

| A reason for using telehealth (medical or otherwise) | 5 [10] | 4 [8] | 6 [12] | 7 [13] | 30 [57] | 52 |

| Criteria used to evaluate whether the case was appropriate for telehealth | 10 [20] | 2 [4] | 12 [24] | 9 [17] | 18 [35] | 51 |

| Diagnosis and impression | 1 [2] | 0 | 0 | 4 [7] | 49 [91] | 54 |

| Evaluation results | 2 [4] | 0 | 1 [2] | 4 [8] | 46 [86] | 53 |

| Recommendation | 1 [2] | 0 | 0 | 4 [8] | 47 [90] | 52 |

*, each subcategory does not always add up to the total number (n=54) due to missing values.

Respondents indicated that additional telehealth documentation collected included electronic new patient “paperwork”, device types used by patient and provider, requirements for in-person follow up, patient location, presenter, language, patient age, day of the visit, method in which the visit was provided, outcome of the visit, follow-up needs, any issues with the visit, need for billing insurance and collecting copays, patient problems/symptoms, vital signs, patient demographics, medication reconciliation, and the reason for audio-only (if applicable). Some additional documentation that was identified by respondents as not collected by their organizations but needed to be included in electronic instead of hard copy forms for substance use clients, updated billing insurance information, copay collection for non-COVID-19 related visits, and antibiotic stewardship.

Respondents were asked the types of personnel that were collecting telehealth visit documentation. It was noted that both clinical providers and non-clinical staff were reported as collecting documentation during telehealth visits. The survey specified that medical staff included primary care physicians, nonsurgical specialty physicians, surgical specialty physicians, non-physician medical staff, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Non-physician clinical staff included nurses and medical assistants, laboratory technicians, radiology technicians, and pharmacists. The office staff included managers, billing staff, coders, and schedulers. The documentation types collected by each group are displayed in Table 5.

Table 5

| Healthcare personnel collecting documentation, n=62 | Clinical documentation, n [%] | Non-clinical documentation, n [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Medical staff | 46 [74] | 16 [26] |

| Other clinical staff | 34 [67] | 17 [33] |

| Office staff | 12 [24] | 37 [76] |

| Other staff | 2 [33] | 4 [67] |

Telehealth visit data was reported to be used for a variety of purposes by the 55 respondents in this area. The most common purposes were for patient care and clinical purposes (90%), reimbursement (75%), providing care to patients with access issues (58%), and quality improvement (53%). Administrative planning (38%), legal and regulatory purposes (33%), and research and analysis (26%) were the next most frequently used. The most common method of collecting telehealth documentation was through the use of electronic health records (EHR) (90%), followed by dictation software (20%) and hand-written notes entered electronically at a later time (16%). Respondents also reported that transcription software in telehealth products (9%), stand-alone telehealth software (2%), and other methods (4%) were used.

Telehealth challenges and barriers

Survey respondents were asked to indicate challenges and barriers their healthcare facilities had encountered in the use of telehealth, in telehealth documentation, data collection, and data use. The most common challenges included issues surrounding patient understanding and satisfaction (65%), constant updates in telehealth guidelines and procedures (49%), legal and risk concerns (43%), and documentation for reimbursement services (43%). Table 6 displays the range of responses reported. Some additional challenges mentioned, which were not choices in the survey, included barriers on the patient’s end such as lack of technology, internet connection, or patient ability to use technology.

Table 6

| Challenges and barriers (n=51) | N [%] |

|---|---|

| Patient challenges with telehealth services (inequities in quality, lack of understanding, lack of satisfaction) | 33 [65] |

| Constant updates of telehealth guidelines and procedures | 25 [49] |

| Legal and risk issue concern (medical necessity visit, incomplete documentation; HIPAA and patient privacy and confidentiality) | 22 [43] |

| Understanding valid telehealth documentation for reimbursement purposes | 22 [43] |

| Payer denial for telehealth visit | 21 [41] |

| Lack of resources and IT support of telehealth guidelines and training | 15 [29] |

| Lack of ability of real-time clinical documentation during telehealth visit | 14 [28] |

| Difficulty verifying patient health insurance coverage | 13 [26] |

| Concern about time involved in telehealth visit documentation | 12 [24] |

| Incomplete clinical documentation (unsigned, undated, insufficient detail) | 12 [24] |

| Telehealth scam and security concerns (cybersecurity) | 9 [18] |

| Other challenges and barriers | 8 [16] |

| Difficulty recruiting qualified staff | 6 [12] |

| No documentation of intent to order services and procedures (incomplete or missing signed order) | 2 [4] |

| Unauthenticated medical records (no provider signature, no supervising signature) | 1 [2] |

Those responding to the survey also had the opportunity to include their open-ended feedback regarding suggestions or comments for telehealth best practices which had not been addressed in the survey questions. Those comments pointed out a concern that technology or reimbursement requirements would take over as the main focus rather than patient care.

Discussion

Respondents to this survey study were predominantly managers or administrators in physician group practices or behavioral and mental health settings. The respondents were from a variety of geographic locations across the United States and were in both urban and rural settings. Further, the respondents reported use of telehealth services in a variety of primary care, mental health, and specialty service areas. The 76 respondents to the survey clearly indicated that the provision of telehealth services increased significantly between March 2020 and January 2021. This was due in large part to the health care restrictions and public fear related to COVID-19; however, the use of telehealth is more than likely to continue in the future beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, insights into the use of telehealth and challenges in the use of telehealth will be helpful for health informatics and information management (HIIM) professionals and new graduates moving forward. Areas of specific interest to HIIM professionals and educators include telehealth patient visit documentation; challenges and issues with telehealth documentation, data collection, and data management; and best practices for telehealth data documentation and management. The results of this study can help clarify these issues for both professionals and educators preparing future professionals.

At the time that the survey study was conducted, January- February 2021, most respondents (62%) had been using telehealth for less than one year. This is significant in that it is clear these respondents’ facilities were new to the telehealth arena and might have faced challenges that more established telehealth users had previously overcome. However, it is also noted that even longer-term users of telehealth increased their use of telehealth within the year prior to the survey so that increased use could also result in new challenges. In addition, multiple changes were made in telehealth reimbursement practices between March 2020 and the time of the survey.

It is clear that the respondents’ facilities were working hard to meet the documentation and billing/reimbursement challenges surrounding telehealth. In order to ensure that they were following appropriate telehealth guidelines, the vast majority of respondents stated that they utilized telehealth policies. While many of these were developed in-house, many also used governmental policies or third-party payor policies as well. In addition to the use of policies for telehealth use, almost all of the respondents stated that they provided training to both clinical and non-clinical staff, including in the areas of clinical documentation and billing and reimbursement. In addition, the majority of respondents provided training in security and HIPAA, another area of interest to HIIM professionals.

Despite policies and training, respondents noted a variety of areas in which specific documentation was "never” or “rarely” collected. Documentation noted to be less likely to be collected included patient identification number, referring and/or consulting physician, and criteria used to evaluate whether the case was appropriate for telehealth. Respondents also noted other documentation challenges such as the fact that some consents were being completed by patients at home on paper and returned by mail, updated insurance information was not always collected, and copays were not consistently collected. In addition, some respondents noted that antibiotic stewardship needed to be documented more consistently. While there were no specific trends noted in the types of healthcare settings in which documentation items were not collected, this does raise concerns regarding the consistency of complete telehealth documentation in some areas. It was not clear if these items were required by the respondents’ facilities and not completed by staff or if they were not required items.

While the majority of clinical documentation was collected by medical staff or other clinical staff, 24% of respondents stated that at least some clinical documentation was collected by office staff. This is an interesting finding and raises questions regarding what types of clinical documentation were collected by non-clinical staff. Telehealth documentation patterns seemed to follow in person visit documentation patterns in terms of the use of direct EHR documentation, dictation, and hand-written notes. Use of telehealth data also reflected the use of in person visit data with use for patient care and clinical purposes and reimbursement being the most common uses.

In spite of efforts to meet telehealth guidelines and to provide policies and training, many respondents stated that understanding valid telehealth documentation for reimbursement purposes, legal and risk issue concerns, and payer denial for telehealth visits were some of the largest challenges they faced in the utilization of telehealth. Another significant challenge was noted to be the constant updates of telehealth guidelines and procedures. This finding is most likely related to two issues: the number of respondents who were new to telehealth usage, and the number of changes in billing and reimbursement within the year prior to the survey.

The most significant challenge that respondents faced, however, was patient challenges with telehealth services, including patient understanding and satisfaction. More than half (65%) of respondents stated that this was a challenge. In addition, respondents noted related challenges such as patient lack of technology, patient internet connection, or patient ability to use technology. This also may be due to the rapid increase in telehealth services provided and patients’ inability to keep up with the rapid technology changes. This is a significant finding, however, that could reflect disparities and inequities in patient care.

Respondents’ final comments regarding best practices for telehealth reflect the above issues very clearly. The comments made by the respondents emphasized concerns about technology or reimbursement requirements becoming the overriding focus of telehealth as opposed to patient care.

This study filled gaps of limited information related to telehealth use management issues and quality of clinical documentation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study also identified challenges and issues encountered when using telehealth for patient visits from the office staff’s perspectives. An additional strength of the study is the contribution of the study results can assist in developing a strategy for best practice for telehealth clinical data documentation and data management.

Limitations and need for future studies

The study findings are somewhat limited by the respondents to the study. While the respondents represented 11 states, both urban and rural settings, large and small practices, and a variety of types of providers, the respondents were all members of the Mid-Atlantic Telehealth Resources Center, and the Missouri MGMA. A larger nation-wide study would provide additional information about the use of telehealth throughout the country and in a wider variety of settings. As the use of telehealth grows, further study will also be needed to fine-tune our understanding of the challenges and barriers. There are a variety of telehealth related issues that will require further study and insight, including implementation of new telehealth guidelines, privacy and security issues, and patient access issues. Further study in these areas could aid in development of best practices in telehealth provision.

Conclusions

It is clear that telehealth was readily, and rapidly, adopted throughout healthcare facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The tremendous growth in the use of telehealth services is not likely to disappear, however, after the pandemic ends. Thus, healthcare entities, and HIIM professionals, need to develop best practices for the use of telehealth, including telehealth documentation, billing and reimbursement practices, and privacy and security.

The results of this study show that telehealth utilization is currently in a transition period. Many changes in telehealth billing and reimbursement guidelines occurred during the 2020–2021 year. As the pandemic wanes, guidelines will change into their permanent (or more stable) form and facilities will find them easier to follow. Also, the newer users of telehealth will become more experienced in this area and will become more confident in their use of telehealth guidelines. Both of these changes should result in clearer policies and procedures for facilities. These changes should also result in more consistent documentation practices, clearer billing and reimbursement practices, and fewer issues with privacy and security.

However, the telehealth transition period will not end overnight. This study did reveal that there are continuing issues in the current use of telehealth. Even in facilities with policies and procedures, there were inconsistencies and challenges. Healthcare facilities must insure that required documentation is collected routinely and that appropriate clinical personnel are collecting this documentation. In addition, facilities seem unclear on specific telehealth guidelines and requirements and facilities are facing challenges with privacy and security. In order to be successful in the telehealth arena, facility staff, and, specifically HIIM staff, will need to stay abreast of the changing telehealth guidelines and requirements. They need to ensure compliance with appropriate documentation, coding, and billing guidelines, Facility audits will be needed to ensure compliance with guidelines. In addition, HIIM staff must work with available technology to ensure privacy and security and to alleviate patient concerns in this area. Finally, facility staff must work to ensure that telehealth services are available and accessible to all patients who desire these services.

HIIM professionals and educators will need to closely monitor the changes in the telehealth arena to stay up to date in this rapidly changing area. As telehealth becomes a more stable fixture in healthcare, HIIM professionals will need to implement standing policies and procedures, useful documentation and coding audits, and privacy and security guidelines. Further education will be required at both the higher education and continuing education level to best prepare HIIM professionals to be successful in this growing area of healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mid-Atlantic Telehealth Resources Center, and Missouri MGMA for their support in distributing the survey to their network connections. Much appreciation also goes to all study participants who provided information that enable the study completion. A special thanks to Lakesha Kinnerson, MPH, RHIA, CPHQ for her contributions to the study and survey design.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Donna J. Slovensky and Donna M. Malvey) for the series “mHealth: Innovations on the Periphery” published in mHealth. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-30

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-30

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/mhealth-21-30). The series “mHealth: Innovations on the Periphery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was not human subject research, and we collected only facility data. Therefore, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not required.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1679-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steingass SK, Maloney-Newton S. Telehealth triage and oncology nursing practice. Semin Oncol Nurs 2020;36:151019. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- North S. Telemedicine in the time of COVID and beyond. J Adolesc Health 2020;67:145-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra A, Ray K, Brockmeyer DM. Rapidly converting to “virtual practices”: Outpatient care in the era of COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020; [Crossref]

- Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. The role of telehealth in an evolving health care environment: Workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012 Nov 20. 3, The Evolution of Telehealth: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going? Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207141/

- Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:957-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith WR, Atala AJ, Terlecki RP, et al. Implementation guide for rapid integration of an outpatient telemedicine program during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg 2020;231:216-222.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- CMS Fact Sheets, “Fact sheet: Medicaid & CHIP and the COVID-19 public health emergency.” Published May 14, 2021. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-medicaid-chip-and-covid-19-public-health-emergency

- Fair Health Organization. “Monthly telehealth regional tracker, March 2020.” Available online: https://www.fairhealth.org/states-by-the-numbers/telehealth. Accessed on 9/14/2021.

- Lee I, Kovarik C, Tejasvi T, et al. Telehealth: Helping your patients and practice survive and thrive during the COVID-19 crisis with rapid quality implementation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82:1213-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metha J. Emerging opportunities-and risks with telehealth in a pandemic. OphthalmolTimes 2020;45.

- Lunt S. Telehealth billing during the COVID-19 national emergency. MGMA Insight. 2020. Available online: https://www.mgma.com/resources/revenue-cycle/telehealth-billing-during-the-covid-19-national-em

- Bell J. Telehealth vs. In-person documentation-the same, only different. J Orthop Exp Inn. 2020. Available online: https://journaloei.scholasticahq.com/article/14538-telehealth-vs-in-person-documentation-the-same-only-different

- Public Health Institute/Center for Connected Health Policy. (2020) “State telehealth Medicaid fee-for-service policy a historical analysis of telehealth: 2013 – 2019”. Available online: https://www.cchpca.org/resources/category/report-publication-policy-brief/

- Skyes Enterpirse, Inc. How Americans feel about telehealth: One year later. 2021. Accessed 2021 April 20. Available online: https://www.sykes.com/resources/reports/how-americans-feel-about-telehealth-now

Cite this article as: Houser SH, Flite CA, Foster SL, Hunt TJ, Morey A, Palmer MN, Peterson J, Pope RD, Sorensen L. Patient clinical documentation in telehealth environment: are we collecting appropriate and sufficient information for best practice? mHealth 2022;8:6.